In his memoir 1967: How I Got There and Why I Never Left, Robyn Hitchcock’s assembled a lovely, evocative, characteristically quirky portal back to that heady time.

What does it mean to perform? I was onstage, and yet I wasn’t; I was playing to someone, and I was alone.

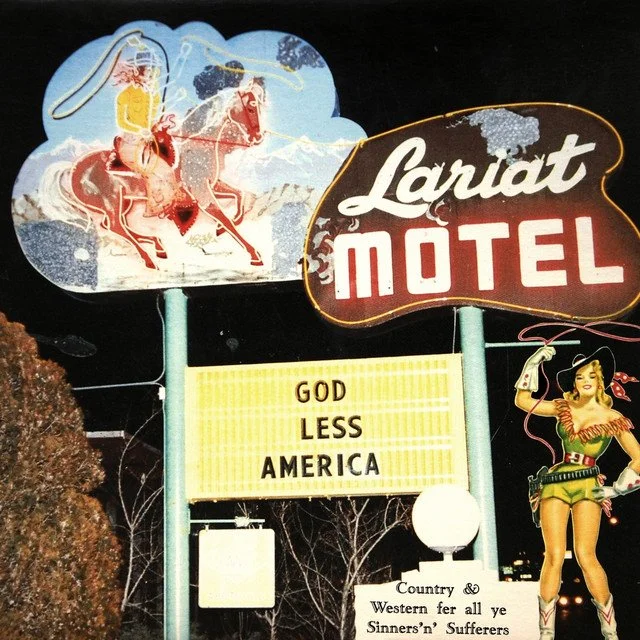

Price is a difficult artist to box-up, for those so inclined. She’s lived in Nashville, Tennessee for decades, and has both courted and been denied Music City’s trappings. A dynamic study in contrasts, she grew up in rural Illinois but sings with a southern accent; her debut album was released on maverick Jack White’s Third Man Records, hardly a Nashville industry staple (though it may be on its way); she cut a live album at historic and revered Ryman Auditorium, waltzing (and rocking) within a storied tradition.

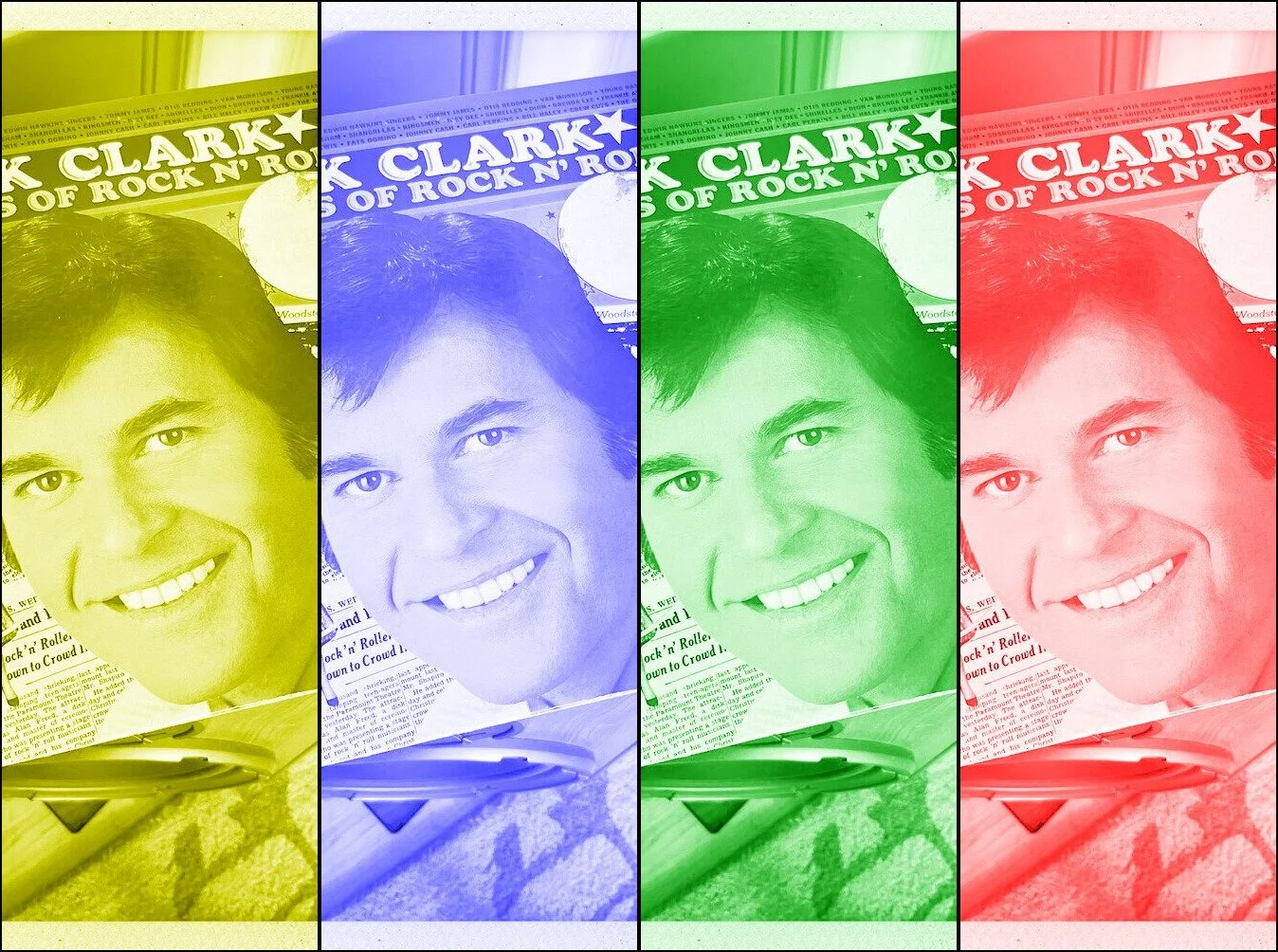

Dick Clark’s face revolving, revolving. This is no fever dream. 20 Years of Rock n’ Roll came packaged with a 'special bonus record,' a cardboard flexi disc emblazoned with, naturally, Clark’s cheery face. The record plays at 33 1/3 rpm, and in an unnerving design bug the spindle hole nailed Clark right between his eyes.

"I can see the singer looking hopefully at the person with whom he’s speaking, seeing the kindness in their shining eyes, understanding the words they offer yet singing, in that eternal melancholia of melody, the real truth."

The voice to which I’m only half-listening sounds familiar, but something’s off, also. I look up blankly from the records I’m riffling through and realize that I’m hearing Elton John, one of his well-known hits from the early seventies, but I haven’t heard this version before.

These images commingle now in memory as my first headlong descent into the strangeness of grief.

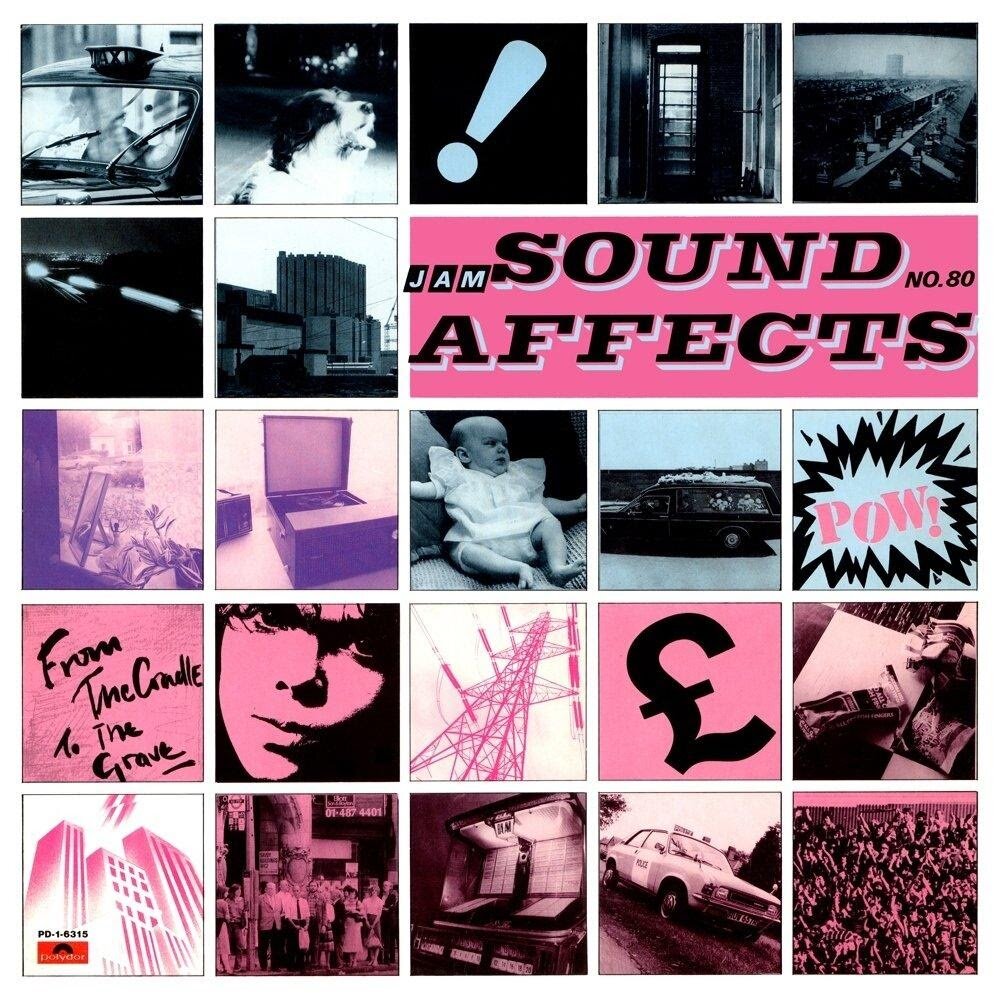

Sound Affects has never left my head. When I listen, the music washes over me in sensations, in snatches of images and phrases, singsong/singalong melodies competing against slashing guitars.

Shuffling through a box of old 45s is like letting fistfuls of soil leak through your fingers. Organic matter, minerals, microbes all seem present on vinyl and worn labels, the grooves veritable garden rows. Heft, ballast, stuff in my hands.

“She sings about idealized romance bruised by clumsy hands; she sings about drinking, and f***ing, and mornings waking up in dubious beds. She sometimes sings about her own career (“Paid”) and about singing. (And singers. Cue up “Steve Earle.”) I’m wondering how much of a story a voice, alone, can tell.”

Infamy is fine. Did you hear the news? John Bonham used a mud shark as a sex toy! Rod the Mod had to have his stomach pumped! Paul is Dead! But when a band gets too famous, literally too big for the room, I resist. My name’s Joe. I’m a fameist.

Such attention to arrangement and production details became Merriman’s signature on the hundreds of compositions—not only jingles and commercials, but corporate musical events and theme-park-ride music—he produced over an impressive fifty-year career.

The tiny flat at 102 Edith Grove in west Chelsea, London, is located in a district that was derided, centuries ago, as the “World’s End.” The name still seems apt: from the looks of things, I could push my fist through a water-damaged wall pretty easily, but I’m scared of what I might find living behind it.

If there are an infinite number of ways to define home, there are also an infinite number of ways to return to it.

At the age of twenty-nine, Larry Brown started writing fiction in earnest. At the age of twenty-nine, Hank Williams drank himself to death.

The history created by my four brothers, my sister, and me is rich and, as in every family, paradoxically commonplace and unprecedented: I am Me in large part because of Them, a random generation of closely-related DNA gathering under the same roof.

Cartwright’s history in bands is vast and eclectic, a testament to his tireless energy, his craftsman’s work ethic, and his love of playing live and with others.

And yet this is how memory, song, and story conspire: I will eternally shame myself with this small incident, and two unrelated cultural moments—a graphic catastrophe, a silly song—will be forever entwined in my mind.

Saturday night brings both pledges and lies of limitlessness, of a night never ending, a jukebox always playing, dance partners always spinning, car wheels revolving on roads that never end in daylight.

I left the bar humming bare traces, the final moments of the song like excavated bones, already fading in the daylight, in the archeology of my head.

Genuine? It’s hard to tell. What does the kid singer know? Does he really understand the burden about which he sings, that his mother’s naked shame buys him his clothes, the complications at that intersection?

My younger brother Paul developed a phobia of listening to records played at the wrong speeds. We’d be listening to a 45 or an LP, and if I moved the rpm knob one way or the other and the song lurched into nasal, pinched hysteria or growled down to a menacing dirge, Paul would cover his ears, his eyes flashing. Sometimes he’d dash from the room; sometimes he’d cry.

Joe Bonomo was named the music columnist for The Normal School in 2012. His books include Field Recordings from the Inside, Sweat: The Story of The Fleshtones, America’s Garage Band, Jerry Lee Lewis: Lost and Found, AC/DC’s Highway to Hell (33 1/3 Series), Conversations With Greil Marcus, and, most recently, No Place I Would Rather Be: Roger Angell and a Life in Baseball Writing. He teaches at Northern Illinois University and appears online at No Such Thing As Was. Visit Joe on Twitter and on Instagram.

The story of one’s adolescence, choked with romantic notions, wordless dreams far more exciting than tedious daily life, is difficult to tell with a clear beginning-middle-end. And I think Townshend knew that.