In his memoir Who I Am Pete Townshend recalled a pivotal episode from the early 1970s. He’d come to depend on amyl nitrate during intense rehearsals for an Eric Clapton comeback show at The Rainbow that he’d taken upon himself to organize. Suffering a wicked comedown at his riverside home in London, the concert and the drug abuse behind him, he felt “cold, depressed, tragic, lost and hopeless. On a dark, wet, winter weekend in the jerry-built cottage at Cleeve, with the river flooding part of the lawns, the wind howling through the badly made doors and windows, my memory pulled me back to a single night when I was 19 years old.”

Riding in on waves of druggy exhaustion and emotional distress, vivid and powerful, this reminiscence is of a few fleeting hours spent under a pier in Brighton on the southern coast of England in 1964 with his art-school friend, “the pretty, strawberry-blonde Liz Reid. We had been together for a riotous night at the Aquarium Ballroom after [the Who’s] gig on the night of a Mod-Rocker street battle on the seafront.” Dodging the drizzling rain under the dark pier, they’d come across “a group of Mod boys in their anoraks. They were giggling as the tide came in, getting their feet wet. We sat with them for a while. We were all coming down from taking purple hearts, the fashionable uppers of the period.”

Remembering all of this a decade later, with his family asleep upstairs, Townshend experienced a “sense of falling and vertigo came flooding back with the flooding river outside—I felt that same sense of depression and hopelessness.”

But I also felt again the remembered romantic warmth of nodding off on the milk-train home in the early hours, with Liz by my side. For a short time we had both felt like Mods. There was something wonderful in all that. We also fell in love, and yet I didn’t go on another date with Liz, never again. The moment with her was frozen, exalted and would always be special.

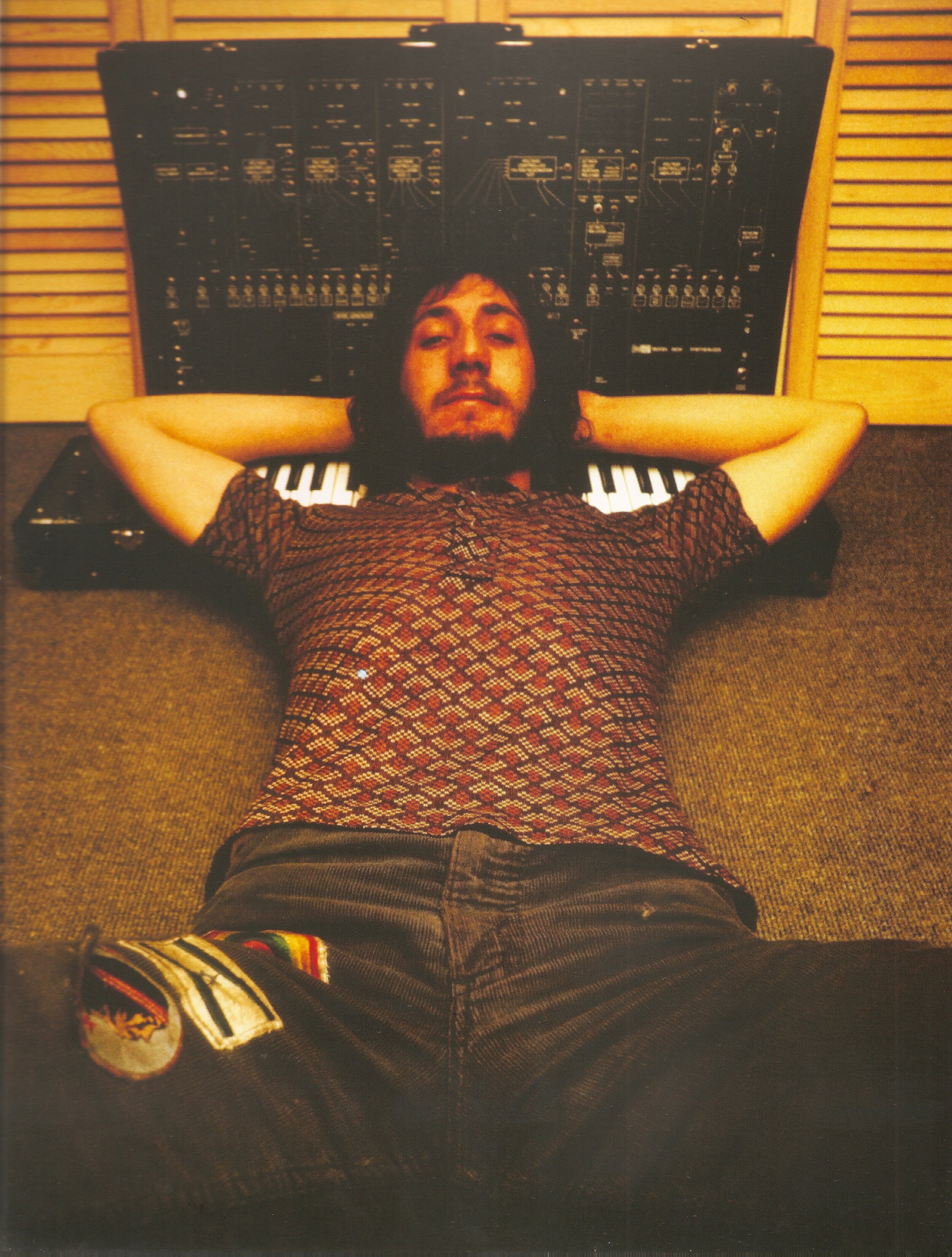

Townshend

The night Townshend remembered the Ballroom, Liz, and the milk-train he wrote in a flash the story that would appear in the inner jacket of the Who’s 1973 album Quadrophenia, a teenager’s rambling complaint about vexed family life, love, identity, paranoia, drugs, fitting in, not fitting in, belief, betrayal, frustrating glimpses of an authentic self—the highs and lows of a typical adolescent week. That the Who’s album originated in a few hours of teenage transcendence says all you need to know. Quadrophenia tells the story of Jimmy, a young Mod in London besotted with male fashion, rock and roll, rhythm and blues, Vespa GS scooters, dancing on speed at all-night parties, and the paradox of striving to be an individual in a community of like-minded, and like-dressed, people. The sprawling and ambitious album contains some of the most powerful songs Townshend’s written and some of the most stirring studio performances from the Who, yet when it was released it was greeted in many quarters as a frustrating failure. The primary complaint (from American audiences generally unfamiliar with the very British ethos of Mods and Rockers) and also from many native Englanders, was that the album’s story was unclear, that Jimmy’s transformation from a snotty, self-absorbed teen to an adult searching for love and transcendence was unearned.

As Quadrophenia opens, Jimmy’s on the brink of suicide, sitting alone in a downpour on a rock jutting out of the dark waters off the coast of southern England. Over the course of the double album we learn what drove him here—he fights with his parents, sees an unhelpful psychiatrist and a hypocritical priest for counsel, crushes on a girl who likes him but who sleeps with his best friend, and craves amphetamines and his fellow Mod mates with whom he forms a rambunctious, laddish community. They dress smartly, ride scooters to dance parties and occasionally on weekends to the beach on the prowl for leather-jacketed Rockers to mess with. Jimmy loves the Who and had at one point strongly identified with the band, but has come to view them bitterly as out of touch with youth and the idealism of rock and roll, a band that has exploited the Mods for subject matter. He detests his dead-end job as a garbage collector and fails to identify with the politics of his older, subjugated co-workers, whom he sees withering into irrelevancy under the unbending and unsympathetic British class system. Exasperated by his recklessness and irresponsibility, Jimmy’s parents kick him out of their home, shortly after which he wrecks his beloved scooter; jobless, friendless, demoralized, emotionally and physically exhausted, doubting his own worth, he swallows a fistful of uppers and takes a commuter train to Brighton where a few weeks earlier he’d danced, fought, and fucked his way through a kicks-filled weekend. Coming down from the pills alongside the majesty and vast anonymity of the sea, he feels restored and he glimpses his true self. Yet he soon runs into Ace Face, a top-of-the-food-chain Mod whom Jimmy had fan-boy worshipped during an earlier weekend but who’s now a harried, faceless, dull bellboy at a posh hotel, suffering the indignities of a blue-collar job. Distressed and feeling deceived yet again, Jimmy pilfers a bottle of gin and briefly stokes his crude and violent side, then steals a small motorboat and rides out to the rock. Having set the boat adrift, there he sits, distraught but contemplative, psychically drained yet ripe for transformation—and the album ends where it begins.

“Jimmy is on his rock, the tide comes in and rages around him. He has made a mistake. He has run to the ocean for help, in his drug-addled comedown he expects to hear a benign and guiding voice, but all that happens is that he gets wet. It rains, not the divine love he prayed for, but freezing rain from the clouds above. He has lost everything that meant anything to him, and now he is cold and wet.”

This is Townshend in “Two Stormy Summers,” a lengthy essay he wrote for the 2011 “Director’s Cut” Quadrophenia box set, essential to anyone who wants a fuller look at one of the great works of musical narrative art of the 1970s.

“Jimmy is loved nonetheless. We love him. We will always love him. In fact, it seems to me we love him far more than the phantom God he cried out to at the end of his very bad day.” In addition to clarifying the story, he revealingly asks a series of rhetorical questions that he’s long heard his detractors pose: “Why would I deliberately avoid a story that made sense? Why would I purposely create characters for my stories who are shadows? Why don’t I obey the easy-to-learn rules of plot construction?”

Townshend’s answers go a long way toward explaining the kind of narrative he hoped to create for the album, a story pulled between cause-and-effect and abstract sensations. “I feel my first audience back in the Mod days commissioned me to say what they felt disinclined or unable to say for whatever reason,” he explained. “For my first Who recording, I wrote some lyrics—‘I Can’t Explain’—and our fans found themselves in those lyrics, they each came and told me their own story. They asked me how I could have known how they felt and what they had experienced. How could I have explained what they could not explain, that they could not explain anything at all? This discovery was an accident.” He adds,

People who liked my songs were able to put themselves inside them and find their own stories. And so rock music differs from all other art and entertainment forms, I think. Usually, the conventional writer, composer or dramatist has a story to tell. A rock composer has to create a tangible and useful hole to be filled. The listener jumps into the music and it is only then that the real story begins. Too much information, too much detail, too much plot, makes this leap impossible.

Townshend’s been explaining, correcting, and elaborating on Quadrophenia since the day it was released. Inspired yet ultimately burdened by the ambitious story, he then characteristically added layer upon layer to the original idea, ultimately expanding the album’s goals to tell not only Jimmy’s story, but the Who’s as well. By the early 1970s, with the band’s career-making Tommy and its massively popular follow-up Who’s Next behind him, he felt pressured to create an album that would provide his band with new touring material and also make sense of their place in rock history. After abandoning a couple of plans, he committed to the idea of presenting the character of Jimmy as an unusual quadrophenic, the four sides of his personality reflecting each member of the Who, who were given “themes” on the album. Though these four motifs blend affectingly as melody, I was never terribly interested in this aspect of Quadrophenia, and neither was the band, I don’t think; it clearly mattered to Townshend, who felt that the Who had earned enough history that their story, which is part of the history of rock music, was as interesting and important as the fictional Jimmy’s.

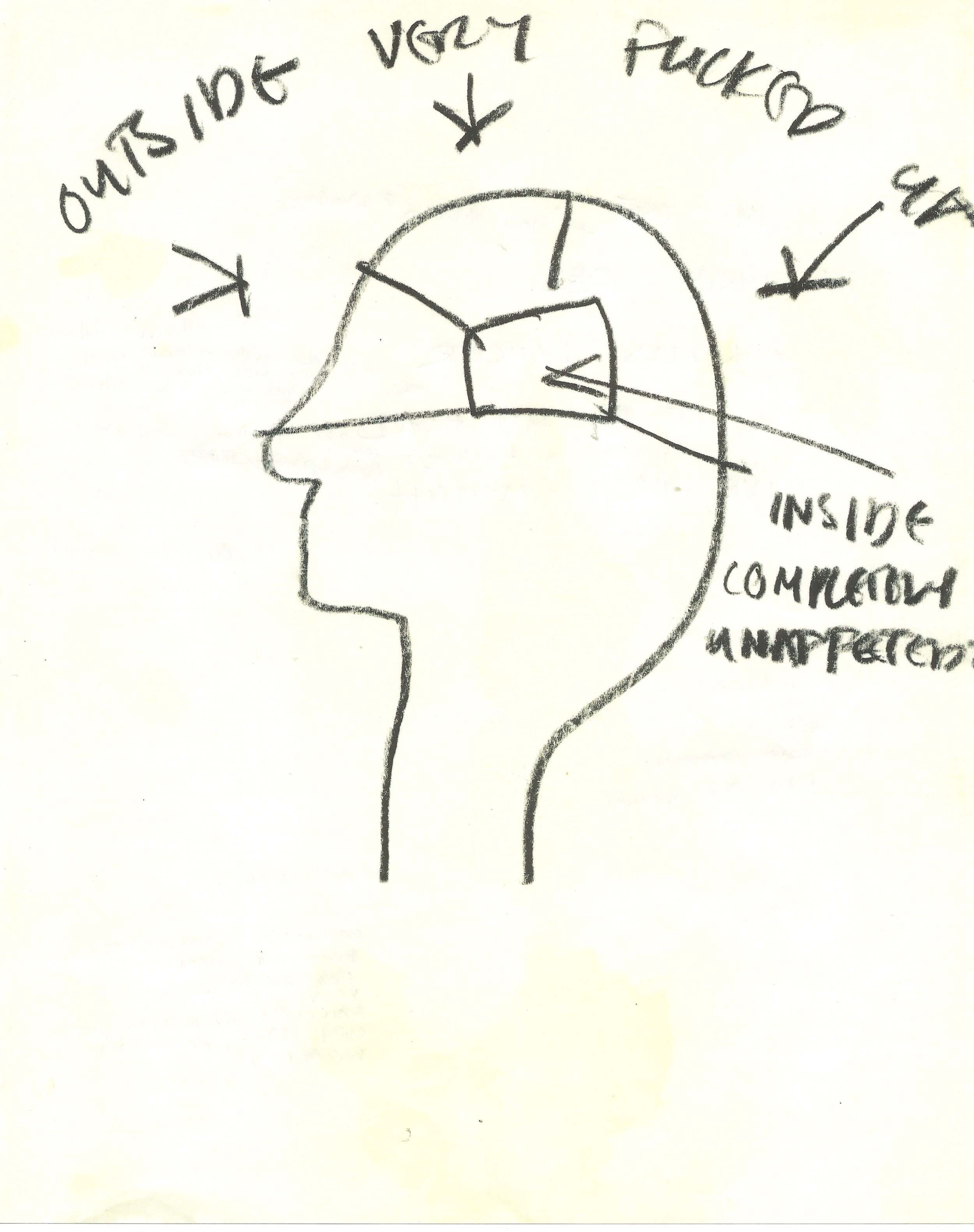

Drawing by Townshend, Quadrophenia box set

Another knot in the process was Townshend’s desire to record the album in quadrophonic sound, which he’d hoped would aurally dramatize Jimmy’s split-four-ways personality, an ill-fated decision that was muddied by the haphazard manner in which the band’s studio was being assembled while they were recording, and by the still-evolving quadrophonic recording technology. (Quadrophonic records never took off commercially.) Finally, he and the band simply ran out of time, with their label eager for the album and a tour looming at the end of the year.

Townshend also faced the practical limits of the album’s length. Even at two discs, he didn’t have enough time and space to tell Jimmy’s story as dimensionally as he’d hoped to. Discarded along the way, gathered in impressive bulk on the ’11 box set, were demos that more fully developed Jimmy’s childhood and adolescence, his relationship with his parents, with his music and with girls, and with other characters on the album, including a tangential storyline involving Ace Face and Jimmy’s father. Quadrophenia’s seventeen songs by necessity leap across plot points, settling for impressionistic, sometimes vague evocations of Jimmy’s real-world problems, joining story points with atmospheric touches such as news and music radio broadcasts and, most suggestively, recorded sounds from train stations and of stormy weather, shore birds, and crashing ocean waves.

I love the album for all this. What some listeners characterize as hazy or incomplete has always felt to me very much like adolescence itself, filtered through memory: shards, impressions, melody translating the untranslatable, words and sense and logic paling in the glare of hormonal vibrations and irrationality, the natural world and the city speaking urgent languages all their own. The story of one’s adolescence, choked with romantic notions, wordless dreams far more exciting than tedious daily life, is difficult to tell with a clear beginning-middle-end. And I think Townshend knew that. He acknowledges that in the song “I’m One” he was trying to capture “a mood that most people can identify with, a transition in adolescence when anxiety and confidence vie for supremacy in our minds and hearts and we can feel fractured.” A touching, four-note leitmotif rises to the surface several times throughout Quadrophenia, a question Jimmy asks that’s central to his problems: “Is it me, for a moment?” That the answer to that question is Yes doesn’t mean that its fleetingness isn’t maddening. Try charting that on Freytag’s Triangle.

Nonetheless, for decades Townshend has felt obligated to defend his album’s perceived shortcomings, to explain, as he writes in “Two Stormy Summers,” how “Quadrophenia taught me that the ‘story’ in rock music is not the same as the plot-driven stories we are used to in movies, novels and TV series, and must never try to obey the same rules.” His most appealing justification for the album’s sparse storyline, beyond the limitations imposed by the album’s length, is that Jimmy worked best as a symbol, stripped of the kind of time- and place-stamped details that situate a character in a specific context. Quadrophenia isn’t “a conventional narrative but a kind of distorted dream-view of two or three days in the life of Jimmy the Mod,” he explains, adding, “It was only later, as the Who went into powerdrive in the recording studio in the early summer of 1973, that it became clear that in order for Jimmy to function as someone with whom the listener would identify, even inhabit, he had to be conveyed and carried by the music, not the story or the characters in it. Jimmy had to belong to the listener, not to the story.” As he composed more and more songs about Jimmy and as Jimmy’s life began to take shape, the character “became less of a boy in his own right and more of an emblem, a cipher for the universal Mod.”

Townshend’s hope? “That everyone who sits to listen to the album finds themselves in it, and finds their own story.”

Ten years ago in The Guardian, James Wood wrote about poring over his older brother’s copy of Quadrophenia when he was thirteen; his brother was five years older. Wood remembers losing himself—as did I, with my older brother’s copy—in the remarkable 44-page book of lyrics and grainy black-and-white photos that came with the album. “Quadrophenia was immediately alluring as a narrative,” Wood wrote, “before I had heard a minute's music.” Ethan Russell’s photographs, taken over the course of two weeks at the beach in Brighton, and in Goring, Cornwall, and the Battersea area near where the Who were recording, cast Terry Kennett, a local kid whom Townshend discovered in a pub, in the role of Jimmy. The shots narrate dour life in post-war London: Jimmy rides his scooter and walks down solitary roads and lanes; argues with his parents in a cramped kitchen; endures dreary breakfasts; hangs with his mates in tiny diners and dance halls; lugs trash; and plays juvenile delinquent in grimy streets throwing stones at buildings and vans.

Most effective are the photos taken in Brighton following Jimmy’s escape, prefaced by a memorable shot of a wild-eyed, besuited Jimmy slouched on the commuter train between two impervious and oblivious bowler-hatted gents reading the newspapers. In the song “Bell Boy” Jimmy marvels that “A beach is a place where a man can feel / He’s the only soul in the world that’s real.” Russell’s photos capture Jimmy’s sense of personal isolation and subsequent identification with the starkly immense shore and the dark, roaring ocean. In the final fifteen photos Russell dramatizes Jimmy’s last hours at Brighton—dejected in a café, walking alone on an empty boardwalk and beach and sleeping under any shelter he can find, stealing the boat and sailing out into the sea. These images—bleak, monochrome, dense—evoke but don’t fully narrate, let alone explain, the album’s plot, but provide a wonderful photo-essay accompaniment to Townshend’s impressionistic story.

As they were for Wood, the songs and photos were my way into Jimmy’s profound alienation and aloneness. Over the decades I’ve listened to this record countless times, bobbing on its dark waves in an ecstatic yet abstractly melancholy identification with Jimmy and his self-doubt and uncertainties, allowing myself to slip into his silhouette, an emblem of youthful disenchantment. (My solitary walks took place along blocks of abandoned buildings and storefronts in and near the D.C. “Old Downtown,” not along the shore, but the gestures felt kindred.) Townshend remarked in Melody Maker in 1973 that at the album’s close Jimmy’s “lost the hang-up of past fears and anxieties into compartments. He’s not saying anymore that he’s got to be tough and a winner, or a dare devil, to earn other people’s respect. He’s just realized the emptiness of those labels stuck on what is just a spiritual desperation which everybody has. In this kid’s case, he’s just going through a speedy maturing process.” He added that, on the rock, Jimmy’s been “stripped of all excuses… the feeling of him being on his knees, but being stronger crying in the rain than he ever was drinking gin, knocking back pills, and kicking Rockers, and whatever it was he thought was the meaning of life.” As a teenager listening to the album in the rec room, loudly on the stereo or more intimately with headphones, I aligned myself with Jimmy’s hard-earned lessons. And I still do.

A more explicitly visual adaptation of these lessons arrived with director Franc Roddam’s Quadrophenia, released in 1979, starring Phil Daniels as Jimmy. Roddam’s film, produced with the Who’s’ endorsement, tidies up much of Townshend’s narrative, making explicit Jimmy’s ill-fated relationship with his girl Steph (Leslie Ash), his betrayal by her and his mates, his dislocation from ordinary working-class life, and his belief in the wonderful but idealized promises of Brighton. The beach fights between Mods and Rockers, briefly alluded to in the album in a couple of songs and via a fictionalized news report, become the film’s central action, given an ambitious wide-screen treatment—they’re immense, rowdy, choreographed battles—and though the final shot of Jimmy’s riderless scooter plummeting off the cliff edge into the water makes it symbolically clear that he’s cut ties with the demanding Mod lifestyle, Jimmy’s fate at the end remains uncertain. I loved the movie and the soundtrack. Nearly drowning in his parka, Daniels and his bug-eyed, desperate portrayal felt viscerally true, especially his growing alienation from his surroundings and his fraught crush on Steph. I longed for his clothes, his style sense, his loose-limbed recklessness on the streets and on the dance floors—boyish unruliness I’d never allow myself to explore but that I envied in others.

Jimmy (Phil Daniels), Quadrophenia, 1979

Like Townshend and long-ago Liz and those giggling boys in Brighton, I wanted to feel like a Mod. In my teen years and early twenties in suburban Washington D.C. I hesitantly self-identified as one. But I was an outsider. I loved the source-brew of 1960s rhythm and blues and rock and roll that bands such as the Who, the Kinks, the Small Faces, and the Creation drew from, and I worshipfully listened to Secret Affair and, especially, to the Jam, and bought up as many Mod 45s and compilations as I could afford. I affixed arrows and targets and pictures of blokes on scooters and blocks of bright neon-colored paper and Mod designs on my bedroom wall.

On the occasional weekend, my high school buddies David, Steve, and I would head down to the now-long-gone bar The Company in Georgetown, in D.C. As David reminded me recently, they never carded there.) Local singer-songwriter Dennis Jay would D.J., having set up a couple of rickety tables near the back on top of which he’d stack numerous boxes of old 45s next to a turntable. I went to The Company less for the scene than for the music. Jay was an older guy, quiet and unassuming, with a shy smile, a slight physique, and thinning hair, but he exuded timeless cool, in part because of his encyclopedic knowledge of rock and roll and rhythm and blues. The place was a quasi-Mod hangout on these nights—it may have been advertised as such, promising hours of 60s R&B, Northern Soul, and Modbeat jams—and in the dark I'd secretly admire the sharper-dressed guys, those who genuinely leaned into the period look and style, removing their parkas after having alighted from scooters parked out front on M street. I'd wear a skinny tie and thrift shop sport jacket, trying my best but staying put in the shadows.

I was sartorially challenged. My poorly pegged jeans, thrift shop suits, and ties mildly compensated for my lack of more genuine (and expensive) Mod gear like a parka, Ben Sherman shirts, Italian shoes, and three-button suits, let alone a Vespa. There was a tiny Mod Revival scene in Washington D.C. in the early- and mid-1980s. I knew that I’d never be able to compete with members of the bands who played in the scene or the fans who attended their shows. Similarly to Jimmy, I instinctively rebelled against the requirements to conform, even as I belittled myself, home after nights at a club or bar or facing the mirror during low points, for not trying harder to fit in, for not being reverent enough, eyeing the kid next to me in class whose pea coat was the perfect color or that one whose tab-collar shirt fit just so. I was too—what, self-conscious? skeptical?—to wear my jeans wet straight out of the washer and to let them dry on me ensuring a snug fit as I’d seen Jimmy do in Quadrophenia, or perhaps I read about it somewhere. I lived at home and didn’t want to have to explain to my mom why I walked around dripping wet. I felt embarrassed enough asking her to haul out her sewing machine to narrow the ankle width on my jeans.

One summer my brother Phil returned from Croydon, England where he’d been visiting his girlfriend’s family, and he presented me with a sky-blue, high-collar dress shirt with white polka-dots that he’d bought at a trendy Carnaby Street boutique in London. No one else in Maryland or D.C. had one that I’d seen, and I wore it with pride on weekend nights. At Poseurs, another Georgetown bar where my friends and I would head to drink and dance, I was approached by Neal Augenstein, the singer of the D.C.-area Mod revival group Modest Proposal, a band I’d gone to see and whose 45 I’d soon play on my radio show at WMUC. Tall and commanding, handsome, supremely well-dressed in Mod style, Augenstein looked a bit like the minor character John in Quadrophenia, and was revered by the small but active Mod Revival community. On the dance floor Neal openly envied my Carnaby Street shirt, and told me so. His public affirmation was childishly pleasing to me, and that was the closest I’d ever get to acceptance in a scene I didn’t work hard enough to blend into.

I wore target buttons and put duct tape arrows on the back of my jean jacket. When I was supposed to have been reading John Donne for class, I instead crushed on Colin MacInnes’s 1959 novel Absolute Beginners, which I read because many in the U.K. and U.S. Mod scenes spoke of it as holy writ, and because Paul Weller had written a song for the Jam with that title. I named my college radio show “Innocent Startings” in tribute to a book and a community I pretended to care about more than I did. When I finally visited London in July of 1988, the Mod Revival was long gone. I walked along Carnaby Street pining for a girl at school who didn’t care about me, bought a striped shirt and v-neck sweater, and thought about Weller, who was then mired in the sad, final days of the Style Council, a ghost commercially. On July 4, I took in a show at the legendary Marquee Club on Wardour Street—the Rolling Stones, the Yardbirds, Led Zeppelin, the Who, Hendrix, Pink Floyd, and countless others had played there at its early incarnation on Oxford Street, and Mod Revival bands such as Purple Hearts and the Chords tore up the joint’s later Wardour Street location—and who was playing but Soul Asylum, an American band from the Midwest. Figured.

Sometime in the mid-1980s a few buddies and I went to see a midnight screening of Quadrophenia on campus. During the scene when Ace Face, played by Sting, stumbles oafishly at his job as a bellboy at a posh hotel, several in the theater crowd around me began shouting, “Sell out! Sell out!” I joined in, screwing up my face in mock-outrage, yelling half-heartedly with them, but I felt stupid, adopting a pose in which I didn't believe; I didn't care if the Face needed to get a real job, if he had to act like a grown-up. That seemed inevitable to me. The pressure I felt to align myself with that crowd reminded me of a shameful incident when I was a kid, about ten or eleven years old, when I shouted an epithet at a family out for a stroll on Bucknell Drive, behind my house. I’d been dared, and dared myself to keep up with my friend Mike, who was older and cooler. The curse felt hollow in my chest—something I couldn't name, but what I now call sorrow—and I felt foolish, an imposter. I immediately felt red-faced and regretful.

The final song on Quadrophenia is the album’s best-known track. Townshend wrote the lyrics to “Love Reign O’er Me” to describe “the most extreme and miserable pathos of the soul ridiculed and abandoned by everyone and everything.” Roger Daltrey’s at his most dramatically expressive (or most melodramatically over-the-top, if you’re not a fan; Rick Moody says “the big production number” feels “cloying” to him) especially in the yearning chorus when Jimmy’s on the rock. A full-throated Daltrey beseeches the rain for love and answers. Townshend writes, “I learned that such an iconic Daltrey bellow can symbolically carry withering sadness, self-pity, loneliness, abandonment, spiritual desperation, the loss of romance, of love and of childhood as well as the more obvious rage and frustration,” adding, “The angst of those teenage years, in which all of us feel misunderstood, is easy to make fun of but it is real and brings my hero, Jimmy, to consider suicide.” Easy to make fun of but real. I love that phrase, which could be the subtitle of anyone’s teenage memoirs.

I recently braved the terrain of boxes in our basement storage room and unearthed “One Little Sheep Goes Askew,” a short story I wrote in high school for my A.P. English class. On the cover sheet I’d carefully drawn in pencil a moody silhouette of my fictional counterpart, a Mod boy clad in a parka with up-and-down arrows sewn onto the back. He’s Pete Blyfield, an introspective high school student who spends his weekends bowling at a low-rent joint and running out on the tab, and his weeknights dreaming and scribbling poetry in his bedroom. Feeling trapped in the tacky suburbs, Pete pines for London and stylish scenes, for the smartly-dressed boys and girls who traipse up and down Kings Road and Carnaby Street. He deplores his fellow students, whom he views as passionless and unstylish clods.

One day, Pete walks into class and his life alters. A new transfer student has landed at school: Dave Cooper, an aloof New Yorker,

dressed in pseudo-Beatle boots, complete with shiny, pointy toes, a pair of jet-black pegged trousers (pleated, of course), a black and white spotted button-down shirt, and—draped casually over the young boy's slender frame—was the hippest, best-tailored, narrowest-lapelled, 1964 suit jacket a silently awestruck Pete Blyfield ever laid eyes on. A one inch bright red tie, razor-clean, close-cropped hair, and a pin that said ‘The Jam’ completed this glimpsing picture.

Pete stands transfixed in the doorway, “staring at Him. A few in the class snickered. Little did they know, though, that Pete was not regarding Him as a screwed-up loser.” [1]

It soon becomes clear to Pete that in Dave he’s met a soulmate, someone with whom he’s intensely connected, and for the next several weeks, he and Dave bond in head-lifting rapture. Pete learns that Dave’s father was in the military, and so he’s lived in many places, including London, a fact that, for the Anglophile Pete, elevates Dave to mythic proportions. The two dub themselves “Stylists” and spend long afternoons in second-hand thrift shops or rummaging through record stores. They meet like-minded guys and girls at D.C. clubs and spend hours together in their bedrooms and at Tastee Diner reading and writing poems, eventually self-printing them in zines and distributing them at clubs and record stores and tying them in thick stacks onto benches in D.C. parks.

One day Pete begins to notice some upsetting changes at school: “A jacket here. A narrow tie there. Prepubescent trousers with ‘Stylist’ labels. Stores selling out of black loafers.”

It seemed to hit him all in one morning. He remembers feeling doom and frantically searching the halls for Dave. He could not find him. He searched with a passion never before recorded and ended in a weeping frustration in the bathroom. He couldn't find Him. He wept.

The kicker: “And soon everyone was writing poetry at Tastee Diner.” The final unraveling comes brutally swiftly as Pete learns that the military has moved Dave Cooper’s family to Idaho. Bereft, Blyfield stands “stripped of soul and meaning” near a busy street. “Before walking into the street he remembers saying ‘It's not we who learn, but the system.’ Or was that Dave Cooper who said that? Or Paul Weller? Or Eric? Or Chuck? Or…. Oh, it will be the catch phrase of the nation soon. Credit won’t matter.”

I laughed out loud re-reading this story again for the first time in decades, and cringed at the melodrama. Blyfield is a poor-man’s version of Jimmy, and a corny stand-in for myself. Yet I have affection for the seventeen-year-old me who believed so earnestly that a stylish mise en scène and well-dressed figures on the stage might quench a deep thirst for experience and wisdom, might, in fact, be the solution. I also still dig Pete’s fierce if narrow-minded desire to step out of the norms and live life as an outsider, even as he cultivated like-minded souls in the Mod community, a brave and single-minded impulse that I’d have been too scared to fully commit to myself. And though the line that Pete mutters to himself as he enters the street is obscure to me now, I still like the cynicism in the final sentence. Writing this feverish fantasy, I was living on the surface as teenagers do, putting far too much faith in style over substance, believing in clichés before I recognized their banality, trusting that passion—that is, Passion—will be the answer to any and all thorny questions that life poses. Poor Pete Blyfield. He has some hard lessons coming his way.

“Intriguing portrait of alienation and condescension,” Mr. Trick wrote at the top of the story. Still attached is the peer-review sheet that two of my poor classmates were obliged to fill out. In answer to the question “Does the story show us anything or give us something to think about?”, they left the space blank. Hilarious, and apt. I certainly felt as if I were pursuing Grand Ideas and Themes when I wrote the story, but I was a kid who hadn’t yet learned the distinctions between sentiment and sentimentality, between substance and sensation. Though the story’s embarrassing and melodramatic, it’s no less true because of that. It was me, for a moment.

The Who are infamous among fans and detractors alike for having never recorded a love song (that’s the reputation, anyway, and the claim’s exaggerated; listen to the transcendent “Sunrise” from The Who Sell Out, among other songs). It’s likely true that as many of Townshend’s love songs were directed to Meher Baba, his life-long spiritual master, as to women. The fact is, his tunes rarely take a point of view other than a young man’s, and Quadrophenia is no exception. “I’m only interested in rites of passage stories,” he declared. He wanted everyone to find their story in Jimmy’s, but that’s a big ask.

“How to recognize a story?” Sylvia Plath asked herself in her journals when she was planning to write a novel. “There is so much experience but the real outcome tyrannizes over it.” The events in Plath’s The Bell Jar (published in 1963 under the pseudonym Victoria Lucas) occur in the mid-1950s, but the novel appeared around the time fictitious Jimmy was enduring his long days and nights of London alienation. Esther Greenwood’s descent into unhappiness bears a striking resemblance to Jimmy’s, yet the boundaries of her experiences are far narrower. Esther struggles to fit in with the other girls with whom she’s spending a summer in Manhattan on a fashion magazine internship. She behaves as decorously as she’s expected to, wears the right clothes in the proper style, is careful with boys, but recognizes that she yearns for something beyond the proper and provincially domestic, low-ceilinged fate she’s been dealt. She wants to write a novel, but stalls. In the second half of the book she returns to her family home in Massachusetts and drifts into depression, ultimately enduring electroshock therapy and a stay in an asylum, all the while struggling to discover her authentic self and admitting to growing suicidal ideation. As Jimmy did, during a particularly difficult day at the beach Esther swims out toward a rock in the ocean, intent on drowning once she’s exhausted herself. She can’t bring herself to die—her body resists the impulse—and at the novel’s end she feels more assured and confident mentally, closer to her “old self” than she has been in weeks.

The differences between the two characters are stark. At his breaking point, Jimmy escapes to the beach where he wanders aimlessly, pilled-up and drunk, taking long solitary walks along the shore into evening and sleeping wherever he can find shelter. For a while, these gestures sustain him; in fact, Jimmy’s far happiest when by the sea. Perhaps happy isn’t the right word—maybe whole. (Townshend has acknowledged that when writing Quadrophenia he drew heavily on Meher Baba’s notion that the sea represents God’s infinite love, and that humans are merely drops of water in that immense body.) The sense of mental cohesion that Jimmy gratefully receives in the salt air and crashing waves is fleeting, so strong is the battle among his selves, the desire to conform versus the need to be an individual.

Esther has fewer options. Though she goes solo occasionally in the novel—walking more than forty Manhattan blocks to her all-girls hotel after an unfortunate late-night date, visiting the beach near her childhood home—those are the exceptions; as a female, her avenues toward freedom are more circumscribed, especially in the era in which she lived and suffered. “Being born a woman is my awful tragedy,” Plath complained in her journals. “From the moment I was conceived I was doomed to sprout breasts and ovaries rather than penis and scrotum; to have my whole circle of action, thought and feeling rigidly circumscribed by my inescapable femininity.” She bitterly adds,

Yes, my consuming desire to mingle with road crews, sailors and soldiers, bar room regulars—to be a part of a scene, anonymous, listening, recording—all is spoiled by the fact that I am a girl, a female always in danger of assault and battery. My consuming interest in men and their lives is often misconstrued as a desire to seduce them, or as an invitation to intimacy. Yet, God, I want to talk to everybody I can as deeply as I can. I want to be able to sleep in an open field, to travel west, to walk freely at night.

And: to escape alone on a train without worry or fear, to walk in solitude by an ocean through the long night, to sleep unmolested on the sand until the sun lifts and with it some measure of peace.

I was fictionalizing myself in Pete Blyfield, not writing autobiography, but I didn’t make contact with much beyond the drama of teenage angst. I forgive my seventeen-year-old self’s narrowness of emotional range and experience, but solipsism is hardly limited to one’s teen years. Writer and editor Joseph Epstein argues that autobiography fails when the writer’s experience “has no generalizing quality…isn't really about anything more than the [writer’s] experience, merely, solely, wholly, and only.” He adds that “true magic is entailed” to make the particular experience of the writer “part of universal experience.”

How to transcend melodrama and banality when writing about adolescence? A challenge for my writing students is to recognize what in their experiences might be emblematic of the human experience, while at the same time embracing the sometimes crushing fact that their experiences, though they feel new, aren’t particularly; add to that the argument that cliché is the death of art, and the order to write about adolescence becomes tall indeed. You can be an inventive storyteller and a master of detail and figurative language like Plath, who saw in Esther not only herself but countless women in her situation, or you can compose stirring songs like Townshend, who, it’s important to remember, purposefully left out characterful touches that might have added unique personality traits to Jimmy in order to leave room for him to become more universal.

Working within a long tradition, both Plath and Townshend use fiction to explore their own lives. A year after Quadrophenia was released, Townshend was asked by Cameron Crowe in Penthouse if Jimmy was “a thinly disguised Pete Townshend.” He answered that the character wasn’t, but that he identified “very strongly with Jimmy in several ways,” before clarifying that Jimmy was “a workshop figure. An invention.” He couldn’t identify fully with Jimmy’s early years—“his romanticism, his neurosis, his craziness. I never went through a tormented childhood. When I was a kid, it was just me and the guitar and the belief that if I ever learned the secret of rock’n’roll I would own the world”—rather, he felt closest to Jimmy “when he’s reached the stage, late in the album, of being stuck on the Rock.”

He’s surrendered himself to the inevitable, whatever that is, and has put all his problems behind him. Jimmy’s not become any kind of saint or sage, he hasn’t even found anything, much less himself. Basically, he isn’t gonna be any different. He’s just reached the point in his life where he’s seriously contemplated suicide—as we all have—and the fact that he chose not to kill himself has left him with a fantastic emptiness. A need to be filled.

At the conclusion of The Bell Jar Esther is alive, her mental health improving, and at the close of Quadrophenia, Jimmy is alive yet drained. That paradox—lost but found—adds dimension to well-worn teenage angst. In fact, paradox might be the way out of cliché when writing about childhood and adolescence. I was too naive to recognize that what Pete Blyfield desperately craved may in the end have brought him little but melancholy and uncertainty (his “anxiety and confidence” at war, leaving him ultimately “fractured,” as Townshend puts it). Instead I use the lame deus ex machina of Cooper’s move to Idaho to bring about Blyfield’s end.

Paradox. Esther and Jimmy both fiercely want to belong to a like-minded group, yet both are fierce individualists. Both dress and behave the way their community’s cultural standards require them to, and both rebel. Both long for the comforts and affirmation of the hive, imagining that their self-worth buzzes therein, but both natively resist the siren call of conformity even as they believe that they need it. Both glimpse their genuine selves only in isolation, and both reject the world the way the world is offered to them. Plath and Townshend strive for their characters’ redemptions at the close of their works, but both Jimmy and Esther, in the infinite present tense of their stories’ ends, are poised unsteadily, unable to solve the riddle.

[1] Yes, reader, I used capital personal pronouns. Forgive me and I’ll spare you excerpts from my two other Mod-related short stories from this era, “The Buildings of 12th Street Circle” and “Shake and Shout!”

Joe Bonomo's most recent books are No Place I Would Rather Be: Roger Angell and a Life in Baseball Writing and Field Recordings from the Inside: Essays. Find him at No Such Thing As Was and @BonomoJoe.

Cover photo by Ethan Russell, Quadrophenia album