October, 2018. A man-about-town sits on a stool on a stage at the Royal Festival Hall. His hair is white-gray. On an acoustic guitar and with the accompaniment of the London Metropolitan Orchestra he’s about to sing a rambunctious, high-spirited rock and roll song that he wrote when he was barely twenty-two years old. Four decades later we’re hearing a bit of melancholy. The arrangement’s at half speed, the voice is shy of the higher notes. Youthful exuberance has been replaced with middle-aged wistfulness, or is it familiar pride wearing an unfamiliar jacket?

The Jam’s run of charting singles preceding their fifth album Sound Affects equals any band’s output in the Punk/New Wave era, or arguably in any era. From “‘A’ Bomb in Wardour Street,” a double a-side paired with a streak through the Kinks’ “David Watts” released in March 1978, through to “Start!”, issued in August 1980, Paul Weller documented, dramatized, and thrilled a young, mostly male audience who tuned in devotedly to his band’s blend of hooks, power, political righteousness, and style. “Down in the Tube Station at Midnight" (October 1978), “Strange Town” (March 1979), “When You’re Young” (August 1979), “The Eton Rifles” (October 1979), the March 1980 double a-sided “Going Underground” and “Dreams of Children”: these are the tuneful roars of lads in pubs, on playing fields, and in streets in front of council blocks on the way to shitty jobs shadowed by low ceilings of expectations. Delivered by Weller (on guitar), Bruce Foxton (bass), and Rick Buckler (drums) with a powerful backline, dour faces, Mod attire, and wry suburban humor, those singles—and the terrific albums that they appeared on or supported, All Mod Cons (1978) and Setting Sons (1979)—are very English and of the Thatcher era, yet timeless. When you’re young, you fall in love with anyone, Weller sang in 1979, as someone sang somewhere in 1679.

“Art School.” “All Around the World.” All Mod Cons.” “The Place I Love.” “When You’re Young.” “Saturday’s Kids.” Listening to the Jam often gives me the impression that I’m playing catchup: somehow the tunes begin before I drop the needle, and I’m left chasing the band, who’s running after the song they created, or that’s created them. The Jam reached a pinnacle with the fierce, scarily powerful “Going Underground,” their first number one single in the U.K. and, to many, the Platonic Ideal of the band’s sound. The sonic equivalent of an epiphany—a loud one—the song gives voice to the disenfranchised, bitter outsider, the one who doesn’t like what’s on offer and who chooses instead to hang out below, away from the brass bands, the “braying sheep” on television, the politicians’ “nuclear textbooks” for their “atomic crimes.” My heart quickens reading the lyrics; accompanied by the band’s full-on assault—the guitars sound as if they’d leap from Weller and Foxton’s hands if the musicians didn’t grip them tight enough—the words fight to be heard, tumbling, gaspingly, from verse to verse, each line arriving like a sudden insight. There’s a startling moment following the eight-bar, half-time bridge where Weller’s Rickenbacker guitar slashes at the surface of the song, slicing it open and awakening the singer from his dreamy sing-song take on the title phrase. impatient with anything in the face of toxic lethargy, groupthink, and lazy consumerism that isn’t urgently, angrily expressed. The moment’s one of the greatest in any Jam song. A slap in the face.

Weller felt that the mood and tone of “Going Underground” marked an end point of sorts for his band, and the single’s other a-side hinted at what was to come. When the Jam were touring the United States in February and March of 1980 the Beatles’ Revolver played on high rotation in the band’s van; writing and recording “Dreams of Children” had led them back to that 1966 classic. A mid-paced, backward tape-laden psychedelic lament, the song churns dreamy nostalgia made bitter by awakening to “a modern nightmare” of “tall dark buildings” and dirty streets, where children’s dreams have little purchase. John Lennon’s dark, guitar-rich, trippy Revolver tracks were the sonic tributaries leading to “Dreams of Children,” and for the next Jam album Weller was curious to see where those currents might take him. (The Jam cancelled the remainder of the U.S. tour after learning of the success of “Going Underground,” and in April, before sessions for Sound Affects began, Weller cut demos of “Rain” and “And Your Bird Can Sing.”)

Meanwhile, Weller was reading quite a bit, and new influences were pouring in, two books in particular striking a chord. Geoffrey Ashe’s 1975 cultural history Camelot and the Vision of Albion explored the Arthurian legend and the Middle Ages’ grappling with Camelot, romance, and the loss of innocence. In 2010 Weller related to John Harris that he’d organized “a bit of a works beano” while working on Sound Affects, “a big coach trip with all the roadies and their wives and the band, and I managed to get them to go to Glastonbury for a few days. I really wanted to go and see where King Arthur and Guinevere were buried,” adding, “there was also that whole ‘Blakean’ thing, about how we’d lost our vision, and been blighted by science, and distracted by politicians, and we needed to get back to a much more natural, pure vision. It caught my imagination. I found it very inspiring.” In Homage to Catalonia, George Orwell, long a favorite of Weller’s, recounted his experiences fighting fascist totalitarianism during the Spanish Civil War in the 1930s, a seminal era that would influence his political beliefs for a lifetime. “Orwell describes arriving in Barcelona for the first time and seeing his own vision of democratic socialism at work,” Graham Willmott wrote in 2003, adding that while there Orwell took note of how “like-minded people travelled from the world with the same ideals as the writer himself. They could barely communicate with each other but all instinctively embraced this new socialist ideal and fought together to preserve it.” Weller absorbed Orwell’s political passions, his provocative ideals and purity of belief, his persuasive argument that artists should respond in their work politically, and felt an instinctive kinship with the writer.

An even greater inspiration awaited. The second episode of the television program Something Else aired in England on BBC2 on September 15, 1979 and, like the inaugural episode, was charmingly, earnestly youthful. This was by design: Something Else was produced to appeal to the young audience that BBC programming had largely ignored, or otherwise misunderstood wildly. The magazine-style show employed a young crew between the ages of sixteen and twenty, and featured appealingly self-conscious hosts, unposh regional accents, spirited debates, a nervy, artistic tone, and music. The Jam, wrapping up work on Setting Sons, bookended the second episode playing “When You’re Young” and their forthcoming single “The Eton Rifles.”

The performances were explosive and striking, the band getting off playing for the crowd of teenagers only feet away from the stage. Equally notable was the content of the episode itself. A segment following the Jam’s performance introduces Ellen, a nineteen year-old single mother of two struggling in a dismal council block (it’s got “a bad name”) in Salford, a mile from the city center of Manchester—she’s also a member of the Something Else production team, lending authenticity to show’s interest in presenting genuine teenage lives. The cameras enter Ellen’s cramped flat, with its grey view out of tiny windows onto grey expanse, and film her looking after her fussy children. In a voiceover, Ellen speaks plainly about the difficulties of paying rent, of struggling up and down the stairs with her pram, her kids in tow, the local youngsters unwilling to assist her. She matter-of-factly shares that over Christmas her flat was broken into, many of her possessions looted and destroyed. The tone of the segment is authentically grim yet moving in its clear-eyed detailing, all the more impressive given the producers’ youthful, unvarnished point of view.

Man-on-the-street interviews with middle aged Mancunians follow (“What do you think of teenagers?”) as well as conversations with local politicians and police about legal drinking and teenagers’ legal rights, a discussion between Tony Wilson, of the upstart Factory Records, and BBC Radio 1 DJ Paul Burnett about the difficulties getting punk rock records on the radio, and, threaded throughout, “punk poet” John Cooper Clarke reciting a list poem while riding up and down escalators in a shopping center (and later a men’s room) trailed by besotted teenage fans. The Jam end the show by righteously storming through “When You’re Young,” Weller and Foxton harmonizing on the bitter lines “It's got you in its grip before you’re born / It’s done with the use of a dice and a board / They let you think you’re king, but you’re really a pawn”—the song sounding like nothing less than a tailor-made theme, a soundtrack to the often frustrated, always wide-eyed young kids whom we’d just watched.

Sitting in on the conversation with Wilson and Burnett was Stephen Morris, a quiet, twenty-two year-old drummer whose band Joy Division Weller had been tuning into with keen interest. New sounds were abounding: earlier in the year Weller had gone to see Gang of Four, a politically-minded band out of Leeds, and he dug their tough, terrific debut Entertainment!, released the same month that the Something Else episode aired. (Weller remembers seeing Gang of Four at The Nashville in West London in 1979; they did play there on February 24, though on that date the Jam were between gigs in Wiesbaden, Germany and Paris, so it’s possible that his memory’s off.) He’d also been turned on by the London band Wire, whose tunes “Dot Dash” and “Ex-Lion Tamer” “were great,” Weller enthused, “pop songs, but slightly jagged, and distorted. I really liked that.”

Joy Division’s two performances on Something Else are extraordinary. (The broadcast was their first and, sadly, last national television appearance; singer Ian Curtis killed himself eight months later.) Jagged, tightly-wound, brittle, anxious, minimal: the hallmarks of Joy Division’s arresting and wholly original sound were laid bare for the Something Else audience, wild-eyed Curtis signing atonally but urgently, dancing and flailing about like a restless marionette. Morris and bassist Peter Hook are locked in, translating a nervous tension agitated further by Bernard Sumner’s busy guitar work. Both “Transmission” and “She’s Lost Control” registered with Weller’s growing sense of his own band’s limits, and its possibilities, and he was enthralled with the nerviness of it all. (And pleased with the band’s unaffectedness: “I remember being pleasantly surprised to find out [Joy Division] were very normal working-class lads,” he said. “In my mind, I had an image of them being ‘poncey art-school, studenty-type’ people, and they were quite the opposite.”) Weller watched, listened, bought the records of these new, exceptionally original bands. And he went to work.

Recording sessions for Sound Affects faced an early uphill climb. “I probably had about five or six songs written upfront,” Weller remembered. “The rest were a real struggle to write. I had loads of ideas: very sort of abstract, vague ideas of what I wanted to do, and how I wanted it to sound, but nothing was actually written.”

Following demo recordings in April (“just me and one of the roadies fucking about, really”), Weller convened Foxton and Buckler at the Townhouse Studio in London in mid-June, and sessions with producer Vic Coppersmith-Heaven began in earnest. The Jam had debuted two songs onstage: “But I’m Different Now” at the Pinkpop 1980 festival in Geleen, Netherlands on May 26, and “Start!” at Victoria Hall in Hanley, England on June 4. Beyond these, the band had little of substance to work with. “So we would jam,” Weller recalls, “and out of that would come a riff” [see “Instrumental” and the backing track to “Scrape Away,” both issued on the 2010 deluxe reissue of Sound Affects] “and then I would start to piece something together. It’s very laborious and expensive, to do that in a studio. But that’s the way that record was made.” He added, “You’re not really familiar with what you’re doing, and you’re just kind of following your nose, but sometimes good things come out of that. It introduces things you wouldn’t normally do. You have certain techniques and ways of working, and it throws all of that stuff out the window. That can be a very good thing.”

Across the summer and fall Weller laid melodies, evocative scraps of lyric, and vocals on top of the tracks, and songs slowly began to take shape. Sources indicate that recording for “Pretty Green” began on June 15, “Dream Time” on the 16th, “But I’m Different Now” on the 17th, and “Start!” on the 19th. On the 21st the band paused to head north and play the Loch Lomond Festival in Scotland, and then began rehearsals for their first visit to Japan, where they would play five well-received shows during the first week of July. On the way back home they stopped at Los Angeles for a July 11 appearance on the ABC-TV show Fridays (looking smart and ignoring jet jag, they played “Private Hell” from Setting Sons and “Start!”). On the 22nd they played the Civic Hall, in Guildford, England, on that day beginning sessions for “Monday.” Nearly a month passed before recording of the group-written instrumental “Music for the Last Couple” commenced on August 27, and, as the boys consciously eyed a label-issued hard deadline, swift sessions occurred for “Boy About Town” (September 1), “Scrape Away” (September 30) “Set the House Ablaze” (October 2), “Man in the Corner Shop” (October 6), and “That’s Entertainment” (October 22).

“Start!” backed with “Liza Radley” (recorded in April) was issued as a single on August 15. The eleven-track Sound Affects LP followed on November 28. On the inner sleeve the band poses in soft-focus in the country near a pond, staring into the middle distance as the rising sun pinks the sky. An excerpt from Percy Bysshe Shelley’s 1819 poem “The Masque of Anarchy” runs on the back sleeve, with phrases such as “Rise like lions,” “Shake your chains,” and “Declare with measured words that ye / Are, as God has made ye, free” evoking the struggle between alienation and liberty Weller sings about inside. A fan had sent him the poem. “In those days, there was a lot of interaction with our fans: a lot of people used to send me stuff, and I’d send them stuff,” Weller recalled. “I just thought it was amazing: it seemed to capture where my mind was at.”

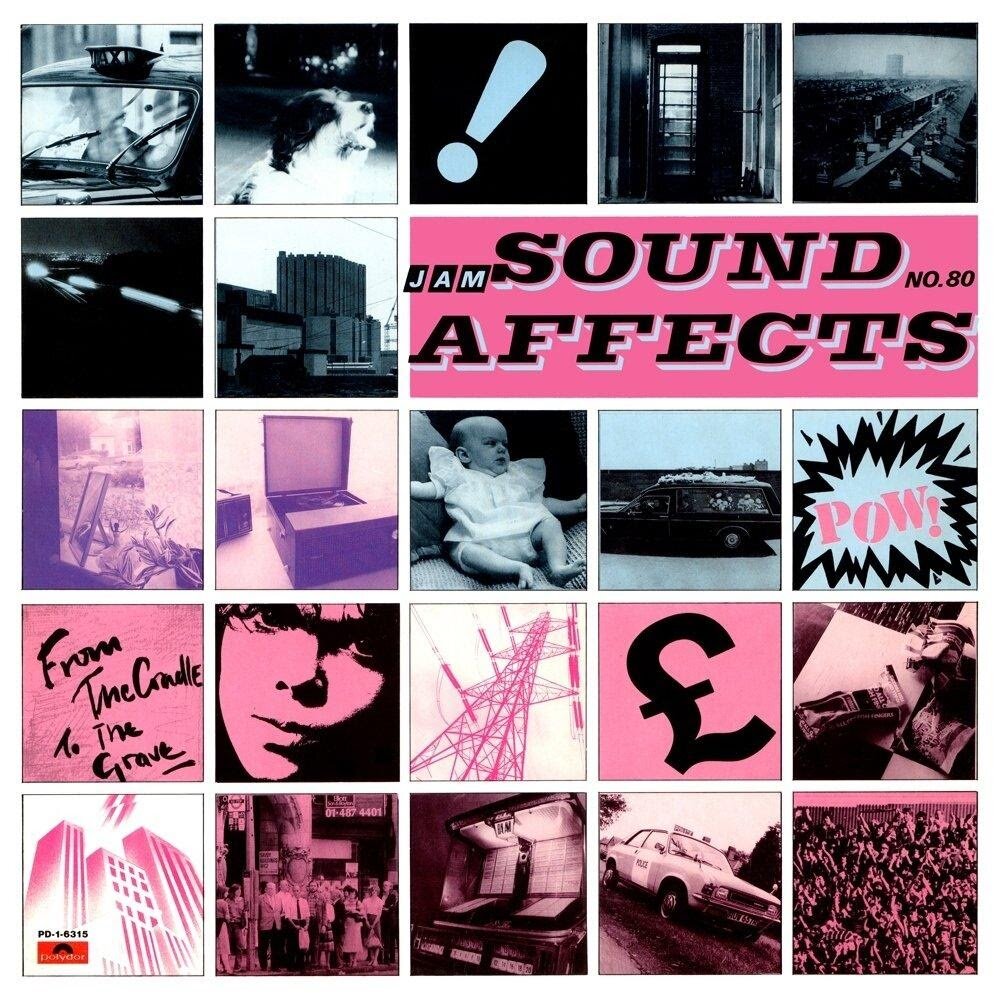

The cover art, based on a mid-century BBC sound affects album that Weller chanced upon in the studio, was an abstract storyboard of images. A taxi cab. A barking dog. An exclamation point. A phone booth. City rooftops. A speeding train. An office building. A baby. A hearse. POW! An open window. A hi-fi. Scrawled graffiti: From The Cradle to the Grave. A face. An electricity pylon. A £ sign. Fish-and-chips. A jukebox. A police car. A cheering crowd.

Sound Affects has never left my head. When I listen, the music washes over me in sensations, in snatches of images and phrases, singsong/singalong melodies competing against slashing guitars. The Jam on Sound Affects sound different than the Jam of the first four albums and the singles. By the time of Setting Sons their songs were becoming glossy and mammoth, stuffed and layered with overdubs. The songs here are leaner, punchier, stripped to bare arrangements that leave spaces in the music you can put your fist through. Before Weller encountered the work of Gang of Four, Wire, and Joy Division, the Jam’s sound had been “very sort of tracked-up: loads of guitars,” Weller reflects, adding, “Now, I wanted to get to the bare bones of the songs.” Overdubs on Sound Affects are rare, a distant piano here, a tambourine and chirpy trumpets there, the occasional backwards guitar; the essential soundscape is of three young men playing live in the studio, moving inside the songwriting process from yet-to-be-named lo-fi funky instrumentals to acerbic songs sweetened with harmonies and simple, childlike melodies. Foxton’s bass is up-front and everything stays spare and wiry. Weller has confessed that he was obsessed with electricity pylons while writing Sound Affects, the images of which he couldn’t shake. I sense them in these songs’ direct impact, in the taut wires of the guitar strings, the amps buzzing, speakers humming, the surges of current in the studio.

The lyrics reflect a minimal aesthetic as well. On songs on earlier albums Weller sang in chewy mouthfuls, cramming as many syllables as he could into a line—the rush of words, ideas, and sensations evoking the urgency and exuberance of youth. On Sound Affects Weller pares back his excesses, trading stuffed lines for skeletal phrases and simple sentences that evoke the primary straightforwardness and unassuming line drawings of a children’s book. Many earlier Jam songs were packed with details—place names and city landmarks and references to laddish gear—while others were cinematic story-songs or Ray Davies-styled character sketches. Here Weller defocuses the lens, and places, people, and things soften to universals. (Still, Weller’s affection for Davies couldn’t be denied; the band recorded versions of the Kinks’ “Waterloo Sunset” and “Dead End Street” near the end of the sessions.) Not that I didn’t puzzle over some of Weller’s Anglicisms when I listened to the album as a teenager. A fruit machine. Pissing down with rain. Sticky black tarmac. Eating your tea. A hardened MP. But mostly, with the exception of the diary-like “That’s Entertainment,” Weller ignores the daily urban/travelogue style for something more elemental, a kind of Mod Aphoristic. If All Mod Cons and Setting Sons are rich with British colors and particulars, Sound Affects offers a monochromatic world, all the more inviting for us to step into the silhouettes that Weller’s sparse lyrics create and find that we fit there.

Songs group themselves together as I listen. “Pretty Green,” “Dream Time,” “Man in the Corner Shop,” and “Music for the Last Couple” suggests one thread of a narrative, “Monday,” “But I’m Different Now”, and “Start!” another. “That’s Entertainment” and “Boy About Town” feel like foils to “Scrape Away” and “Set the House Ablaze.” The album gives the impression of being a soundtrack of a weekend: a kid in his early twenties strolling up streets and down streets, worn paperback copies of Shelley and Orwell under his arm, suffering existential crises in the supermarket watching people go crazy, enjoying pints in the pub on Friday night where he hears about a former mate devolving into fascism and hatred, on Saturday night where another’s becoming twisted by cynicism, heading home drunk and writing all of these sense impressions down, struggling to see splendor in the daily dross, waking up hungover on Sunday and strolling past a church, thinking on the ironies of the class distinctions of those worshipping inside, dreading work on Monday, where he’ll dream of boats and planes to spirit him away and pine for the girl whom he’ll see there. He’s different now, he’ll show her…

Weller adorns both “Pretty Green” and “Man in the Corner Shop” with simple melodies, yet they feel like anti-lullabies. “Pretty Green,” the album’s opening track, sets the template: simple, direct, unadorned, and danceable, the unassuming melody sweetening a morality tale about the free market. Weller’s always been interested in class—few English songwriters in the late 1970s weren’t—and many of his songs decry the inherent unfairness of capitalism while cranking the amps. “Pretty Green” puts it simply: I’ve got a pocketful of cash and the slot machines, sandwich shops, and jukeboxes will empty it. “It’s something that I learnt on my own,” Weller sings resignedly, “That power is measured by the pound or the fist, it’s as clear as this.” By the time Foxton sweetly sings the title phrase against the repeating verse, the song’s turned dreadful: you can’t do nothing unless it’s in the pocket. Sweet dreams. I hear Joy Division/Gang of Four influences here, less in the grim lyrics than in Foxton’s machine-like bass lines and Buckler’s hi-hat work, wound-up tension momentarily relieved by the burst of the chorus before the perpetual motion of the verse-machines—“I’m gonna eat, and look for more”—reminds us of capitalism’s pure hunger.

The incongruities of class are especially apparent in the mid-paced “Man in the Corner Shop.” The simple, pleasant melody describes a shop owner, his customer, and the customer’s boss, each measuring his worth against the other—envy, pride, and power competing. The shop owner’s life is hard, yet it’s nice to be his own boss. The customer, envious of the shop owner’s freedom, will rue his own fate tomorrow at his stifling factory job, where his boss will haughtily smoke cigars he purchased from the shop owner, who, it turns out, is tired of struggling and dreams of owning his own factory: The End. The timelessness of this cycle of complacency and resentment is mocked in Weller’s descending “la-la-la-la-la”s, honeyed in affect but bitterly pointed. The Jam loved their la-la-la’s and their fa-fa-fa’s—think “David Watts,” “Saturday’s Kids,” “Going Underground”—yet on Sound Affects they sound less like drunken-lad pub or football chants or rallying street-cries and more like pre-language wordless expression, filling in the blanks of Weller’s abstractly minimal lyrics, responses to the emotional content that the words evoke. Do the “la-la-la-la-la”s here blissfully deny class warfare that’s as old as dirt, or perversely sing along with the struggle? The song’s bridge, one of the few passages on the album I still puzzle over, brings the three men together in church where they pray communally, “for here they are all one, for God created all men equal.” Is this a calming insight, or ironic satire? Weller fairly spits out the word “created.” What do your ears tell you?

A swirl of backwards guitar ghostly percussion disembodied falsetto-cry slowly ascends and as slowly retreats and as we’re lulled to hypnotic rest…POW! the band comes crashing in with the opening verse of “Dream Time,” a fraught cry against commercialism. The swingin’ chorus buoys things, until we stop dancing and listen to the words. The singer’s anxious and sweating, and he’s taking stock of a nasty cityscape that he wishes to flee but that traps him. The usual balms—pretty girls and city lights—fail to distract from his paranoia or soften his nightmarish discovery that his love comes in frozen packs bought in a supermarket.

Weller claims that he was in thrall to Michael Jackson’s Off the Wall, released in August of 1979, as he was writing Sound Affects, a record that he asserted was as strong an influence as Revolver. A deep background influence, perhaps; any dancing to Sound Affects stems more from desperation than joy. I do hear Jackson in the surprising, thirty-five-bar middle of “Dream Time.” The band interrupts itself, striking the same chord for a few bars as if distracted by a new, incoming idea, which Weller reduces to a simple premise: “It’s a tough, tough world,” and so, “You’ve got to be tough with it.” He repeats the second phrase as his band gains steam, surer inside this new conceit, though they’re playing a different song now. Then Weller leaps for a falsetto, singing variations of tough with it as a horn section arrives out of the blue and punches the phrase with gusto, and the nightmare turns into a dancefloor. If this propulsive section grew from a studio jam, Weller was smart to surrender to it and see where it took the band. Buckler lands on a four-on-the-floor groove and the thing really moves, a pop-up night club to dance away all of your problems. To my ears it’s among the most moving passages on the album, as Weller’s falsetto surprises him into the complex joys of the moment. A sweaty, full-body groove against hate and despair, the passage points to the soul/R&B sound that the band would consciously adopt over the next two years. The Jam infamously declined to smile in nearly all of their publicity photos, but it’s tough to imagine that they’re wearing scowls as they’re laying this down.

Nothing less than the theme to a dreary job, the band-composed “Music for the Last Couple” is a post-punk version of the kind of music that played behind scenes of bustling factories in old Warner Brothers cartoons. The syncopated rhythms evoke pistons, cogs, and spinning gears, and a punch-in/punch-out, company-man joviality; he’s hard at work yet happy for the opportunity. That is until his inner voice rises to the surface of the smooth-gliding office works: I think of boats and trains and all those things that make you want to get away… The moment of yearning passes quickly, is dismissed, and it’s head down and back to work.

The silver lining of a monotonous office job is that he might run into her there. “Monday,” one of Weller’s great love songs, arrives after the stern “Pretty Green” and its tender conjuring of a work romance softens things. “There were always romantic songs on Jam albums—a long line of them,” Weller insisted in 2010. “But I like the twist in [“Monday”]—that Monday’s probably the least romantic day you can think of.” He adds, “It’s very English; really suburban.” Gorgeous in its lyric and melodic simplicity, especially in the soaring chorus, “Monday” is a dreamy reprieve from the album’s gloom, and is strikingly vulnerable: “Tortured winds that blew me over / when I start to think that I’m something special / they tell me that I'm not / and they’re right and I’m glad and I’m not.” In one of the more powerful discoveries on the album, Weller sings, “I will never be embarrassed about love again.” That he sees her on Mondays, and not on the weekends, suggests that whatever romance he imagines might be in his head, but his gratitude for her redemptive presence in his life is raw and real.

“But I’m Different Now”— the other love song on Sound Affects—hearkens back to an earlier Jam sound. A strutting avowal given charge by Weller’s raw guitar riff and Buckler’s pace-quickening hi-hat work, the song arrives and vanishes in under two minutes before the singer, or his girl, has much time to doubt its promises and apologies. I scrawled the lines “Fun lasts for seconds, love lasts for days / But you can't have both” in my high school English notebooks, romantically indulging the cynicism and marveling at the way it’s rescued by the heart-pumping stomp of the music. Foxton’s ascending bass line in the chorus sounds like the heart when it’s happy. And those “hay yay-yay-yay-yay”s in the bridge—yet another moment where Weller surrenders to the wordless language of excitement.

There was apparently some grumbling among the executives at Polydor Records when the band insisted that “Start!” be the advance single, not “Pretty Green,” the label’s choice. In retrospect it’s clear how sharp the band’s instincts were: “Start!” is one of the Jam’s outstanding singles, a meta-song that’s as infectiously joyous as it is slyly smart. Kicking off with the indelible bass riff from the Beatles’ “Taxman” (another nod to Revolver), the song establishes its danceable argument: if we communicate for two minutes only, it will be enough. “The lyrics to that reflected what I was thinking sound-wise: to be very minimal, and make the point as quickly as possible, and get in and out,” Weller says, adding, “I was very, very hung up on communication.” He relished the power of the pop song “to communicate so much in such a very short space of time. I was really drawn to it.”

Weller had written about alienation since the first Jam album (“Away From the Numbers”) and it’s an obsession threaded throughout his songs—listen to “Standards,” “In the Crowd,” “Strange Town,” “Private Hell,” and others. Yet this is the first song where a solution for the debilitating effects of isolation might be found in the song itself. Like so much great rock and roll, “Start!” is about rock and roll—the 45 single in particular, that two-minute window onto the human condition issuing weekly from the radio, each more mind-bending or hip-moving than the last. But “Start!” isn’t about easy answers; he’s singing, after all, to someone who feels as “desperate” as he does and who “loves with a passion called hate,” someone for whom a cheerful night out at the club or evening alone with a stack of 45s might ease things but who will likely wake up the next morning faced with the same old dilemmas. What you give is what you get, Weller wryly reminds us as two minutes end and the needle lifts.

Rock and roll might solve alienation for a couple of minutes, but if it can’t be an antidote to racist indoctrination it can evoke its nastiness. Weller recalled that in England in the late 1970s “you used to see a lot of the audience getting hooked into that whole National Front thing: young kids, a bit like that film This Is England [a 2006 drama about early ‘80s U.K. skinheads, written and directed by Shane Meadows]. You’d see elements of it in the audience, or the kids you used to meet at sound-checks, who seemed susceptible to that sort of brainwashing.” Weller wrote the confrontational “Set the House Ablaze” in response to this unwelcome development.

The singer’s addressing a mate whom a mutual friend had seen in the pub. These days he’s wearing the fascist uniform: leather belt, black boots. He looks macho, but “oh, what a bastard to get off,” the singer laments as the lockstep, martial beat behind him leads inevitably to the explosive chorus, Weller’s guitar slashing in anger at his mate’s vile conversion. We never learn precisely what he says that’s so incendiary, a bit of narrative brilliance on the part of Weller who evokes the foul things the lad’s spewing with the image of the strutting, malevolent uniform. In another powerful move, Weller cuts the second verse short, as if he can’t hold back the rising hopelessness in the song’s chorus, in which he mourns:

I think we’ve lost our perception

I think we’ve lost sight of the goals we should be working for

I think we’ve lost our reason

We stumble blindly and that vision must be restored

In the twelve-bar middle, this reflection yields to a kind of desperate yearning. “I wish that there was something I could do about it,” Weller sings—and listen to the way Buckler’s rolling drums mimic the singer’s turmoil—“I wish that there was some way I could try to fight it, scream and shout it.” He’s screaming and shouting in the very song in which he’s admitting futility, of course, the irony burned to a crisp like everything else in this ferocious song.

Wordless passages convey so much on Sound Affects: the menacing opening riff; the rigid, portentous four-in-the-bar beat; the whistling in the opening bars and throughout that evoke nasty, goose-stepping marches. In a troubled, 35-bar passage that follows the second chorus, a disembodied voice begins uttering, rising through the smoke. We hear stray phrases—it is called indoctrination; nothing to do with equality; nothing to do with humanity; cold, hard and mechanical—as the fuming opening riff drags itself back in and the song explodes into the chorus again. Yet nothing is settled. The whistling starts up again, competing with the singer’s and the band’s indignations. A violent encounter. Tables are turned over in the pub. Pint glasses go flying.

And then surprisingly, movingly, and then not at all surprisingly given the album we’re listening to: those soldierly whistles morph into desperate “la-la-la”s which Weller sings near the top of his register, the band storming behind him, of a different, far more complex order than the wordless passages we hear elsewhere. For one: which of the characters are chanting them? And why?—out of brutal triumph on the way home from the pub, or as a naïve stay against that brutality? As many times as I’ve listened to the song, I’ve never been able to figure out the origin point of these “la-la-la”s, let alone Weller’s reason for singing them, here, near the end of a conflagration of a song that ends in ashes. “Set the House Ablaze” is one of Weller’s greatest songs and one of the Jam’s almightiest studio performances: scary, righteously pissed off, unavoidable, nearly out of control.

I imagine that the singer heads back to the pub the next night, less on the lookout for his adversary than to soothe his own nerves. Yet there he quarrels with another mate who’s morphing into a lesser version of himself. A bothered, rhythmically arduous protest, “Scrape Away” closes Sound Affects unhappily. To the singer, his friend’s a victim of twisted cynicism, surrendering to hopelessness, accusing the singer of being a naïve dreamer and openly mocking his idealism. Begun in the studio as a band-composed instrumental jam, “Scrape Away” never feels entirely comfortable with itself as a song. Weller wrestles his lyrics to meet Foxton’s anxious, rising bass line, Buckler’s obstinate drumming, and the song’s odd meter, only in the choir-like held notes of the chorus finding release of sorts, as he bids his jaded friend some advice: you need to get away, you need a change of place. Yet the questions in the verses—“What makes once young minds get in this state? Is it age or just the social climate?”—remain, nagging, unresolved, the song fading away as a voice mutters in French and a dire siren-cry issues from Weller’s guitar.

“Coming home pissed from the pub and writing ‘That’s Entertainment’ in 10 minutes, ‘Weller’s finest song to date’ hah!” So wrote a half-grinning Weller on the sleeve notes to Dig The New Breed, the Jam’s 1982 live album. (Twenty years later he acknowledged that the song’s lyric was based in part on a similarly-named poem written by Paul Drew, who sent it to Weller’s Riot Stories publishing imprint.) A list poem of mundane details sung in a dreamy, sing-song melody, “That’s Entertainment” is different from anything else on Sound Affects, yet is in many ways the album’s centerpiece.

Playing on his acoustic guitar, complemented by Foxton’s anchoring bass and by eddying backwards guitar in the later verses, Weller dryly moves from one observation to the next, the song unspooling matter-of-factly. Police sirens, a crying baby, a howling dog. Walls splattered with paint, a garage band rehearsing down the street, a sticky blacktop. A freezing cold flat, a pneumatic drill outside, a ripped-up phone booth. Life in all of its ordinary, graceless details, strung together in kind of threnody to the everyday. “That’s entertainment,” Weller sings in the chorus in a poignant blend of awe, sarcasm, cynicism, and innocence. A picture book of urban and suburban familiarity, the song echoes the album’s cover art as a kind of storyboard, stark images and events strung together yet cohering: nothing really matters among these things, yet, as snapshots of the life we take for granted, each is profoundly significant. You want to read the song as satire or irony, yet Weller sings with such affection about blinking lamplights, boring rainy Wednesdays, kissing lovers, feeding ducks in the park—even a kick in the balls—that the earnestness is deeply affecting, and touching. “That’s Entertainment” was released as a single in West Germany in January 1981, and proved popular as an import in the U.K. where it reached number 21 on the charts. It’s since become a Weller standard.

Generally a dour album, Sound Affects comes to life with the wry “That’s Entertainment” and erupts with joi de vivre in “Boy About Town,” the freest and least cynical song here. Another childlike melody elevates the story of a happy afternoon that the singer spends in the city, “on top of the world” as he glides up and down streets, window shopping and people watching. He’s the guy in “That’s Entertainment” now gushing about everything, the wind blowing him about ecstatically, though his ear’s still tuned to minor notes: that propelling wind “won’t let you go / ‘til you finally come to rest and someone picks you up / up street down street and puts you in the bin.” Until then, he’s content watching rainbows and the folks around him “go crazy,” wishing only to go his own way, where he wants, when he wants. Weller’s in a great mood here, and he writes a melody and arrangement to match, the song bursting into technicolor in the instrumental break where two trumpets sing the verse melody and where a grin on Buckler’s face as he plays overjoyed tumbling fills on his tom drums is practically visible. I guess that “Boy About Town” is the third love song on Sound Affects. Just before that break Weller cheerfully sings another round of “la-la-la”s—it’s the album’s vernacular, really—and here as in “That’s Entertainment” they’re stripped of the complexities of those sung in “Man in the Corner Shop” and “Set The House Ablaze”: joy spilling over the rim of the words we use to express it, pure language as pure song, the album’s gift for its listeners.

Moving among his beloved Rickenbacker, Eccleshall, and Gibson SG guitars, Weller punches the air and adds harsh dissonance and slashing emphases to the songs on Sound Affects, the last truly great rock and roll guitar album he’d make. In 1982 he’d disband the Jam and form the Style Council with keyboardist Mick Talbot and numerous side musicians, indulging an eclectic love for soul, funk, jazz, and R&B, and Continental fashions. His tongue-in-cheek songs become more topically political and stylistically sundry, and he seemed to have lost his interest in the sparse soundscape and fragmented, universalized songwriting style of Sound Affects.

Yet he regards the album with great affection. “I still feel that it was our best record,” he remarked to John Harris in 2010, adding, “To me, it still sounds fresh.”

Funny what gets in and stays there. I remember dialing the 9:30 Club concert line one night in the early 1980s and marveling as a few seconds of the spirited chorus to “Dream Time” burst through the phone. The Jam played Ritchie Coliseum on the campus of the University of Maryland on May 14, 1982, and maybe the club’s promoters were hosting the concert, or perhaps I’m confusing this with an ad for the show that aired on WHFS 102.3 FM, my favorite radio station—I can’t recall the context now, but vividly recall those few seconds of the song surging through the air, its melody and harmonies scoring an evening or a weekend for me, the very soundtrack of my excitable adolescence. My older brother went to the Jam show at Ritchie Coliseum, and afterward told me that they opened with “Boy About Town.” I wasn’t there and still I see a spotlighted Buckler, his sticks raised over his head, counting in the song, the night, the era.

I’m hanging out with some buddies at Variety Records in Wheaton Plaza, the mall a half mile from my house in Wheaton, Maryland. “Set The House Ablaze” is playing in the store—Sound Affects had been out for a year or more—and my friends and I, poised at the Teenage New Wave Punk threshold, are goofing around, wasting time, gawking at the albums we can’t afford to buy. I’m startled by a BANG on the glass window, look in the direction of the noise, and see a punk rocker outside glaring confrontationally at me through the window. My chest goes cold. He either gives me the finger or mutters something before stalking away (in feverish retellings of the story, he does both) and I’ve been imprinted. I hadn’t noticed the guy in the store (he had to have been there, right?) and—moments later as the frightening march of “Set The House Ablaze” leads to the detonation in the chorus—I know I’ll never forget him.

Last week, across the street from my house a girl wearing orange and black made several trips from her car to the house unloading stuff for a Halloween party. My window was open. She’d left the stereo on in her car and Tame Impala’s “Yes I’m Changing” played loudly, filling the air. If I hear that song again in ten or twenty years I’ll remember this girl, Halloween, and an evocative, ordinary afternoon tableau made tangible by a song. How sound affects things.

Paul Weller’s 2018 performance of “Boy About Town” at the Royal Festival Hall is a gently worn paperback; the song’s soft from having been caried around for a couple of decades. There are more than twenty Jam, Style Council, and solo albums and countless singles between Sound Affects and this moment, and the man who’s singing now is a sixty-year-old fitting his hands and voice around an excitable song he wrote when he was barely twenty-two. How’s that accomplished? Weller’s performed “Boy About Town” fewer than twenty times as a solo artist, and to listen now is to hear a man try and plug himself back in to a young man’s humming current. No longer being that young man, Weller adopts a wistful tone, inevitable given the weather in his voice and the decades removed from the shooting sparks of the song’s composition. The unobtrusive accompaniment of his backing band and the tastefully arranged orchestral strings create a temperate sound far from the joyous, ardent, Mod stomp of the Jam, and Weller, recognizing this, sings in a blend of melancholy and gratitude, bittersweet that the song scores a life of a lifetime ago, grateful that he still feels inspired, and is able, to sing a song about the ways in which the ordinary, daily world might come still alive to surprise us, flaws and all.

Joe Bonomo's most recent books are Field Recordings from the Inside (music essays) and No Place I Would Rather Be: Roger Angell and a Life in Baseball Writing. He blogs at No Such Thing As Was and you can visit him at @Bonomo Joe.