The Empty Bottle, on Chicago’s West Side, is filling up. I order a beer and a shot. The guy next to me is about my size. In the club’s mid-dark, he’s a body mass ordering a drink. If I’ll remember anything about him it’ll be his barely-there-ness, some politeness directed generically at the barmaid. I don’t know who he is. He’s there, and he’s gone.

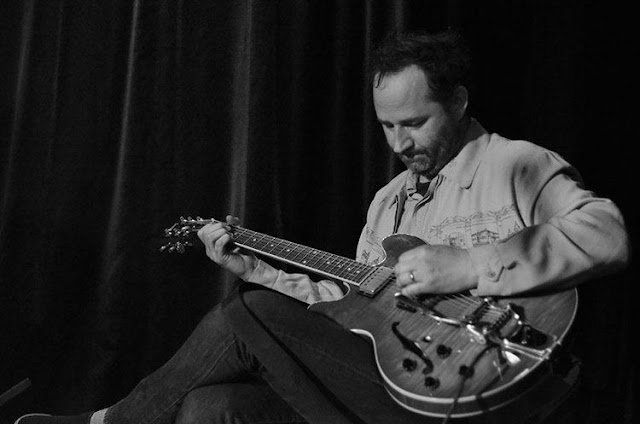

An hour or so later, he’s onstage. I can see him more clearly now, though he’s bathed in red light and surrounded by a band. Dressed in a flannel shirt, ripped jeans, and deck shoes, he looks like a doughy fan who’s been given a chance to jam onstage. Or he looks like Bob Mould’s little brother. Either way, it seems right to me. Onstage, Greg Cartwright is friendly, loose, passionate, and shy, a strange blend that works both to intensify and to deflect attention, as if once he sends a song into the air, he wants to disappear inside of it. The moody tunes sung by this ordinary-looking guy tell stories of despair and elation, romantic politics and personal failings, scored with pre-Beatles melodies and chord changes, country yearnings, garage-rock pummeling, and R&B sweat and ache. He plays left-handed, his eyes often trained down at his guitar, as if he’s really singing to the instrument and to the links among head, heart, and the world. He doesn’t talk much between numbers—he’ll maybe crack a joke about a botched lyric or a fucked-up ending—letting his tunes say everything that needs to be said. In any given song, his voice moves from screech to Neil Young, from howl to Dave Prater, from raspy growl to Lou Reed. What a difference a few feet of elevation, a guitar, and a clutch of tragically good rock-and-roll songs can make.

“Seriously, if it weren’t for my wife I would live in a lean-to in a field with a pile of records. In the rain.”

On June 29, 1971, the City Council of Memphis, Tennessee, voted to officially change the name of a three-mile stretch of Highway 51 South, between Shelby Drive and East Brooks Road, to Elvis Presley Boulevard. Councilman Downing Pryor originally wanted the entire stretch of the highway from Mississippi to northern Memphis so named, but officials of Bellevue Baptist Church objected to their house of worship being located on a street named after Presley. A sign was erected on January 17, 1972, a week after Presley’s thirty-seventh birthday, at a ceremony outside of Graceland, with Memphis Mayor Wyeth Chandler and Elvis’s father Vernon Presley in attendance. Two months and one day later, Greg Cartwright was born in Frayser, a Tennessee town of about 45,000 people, a small peninsula between two rivers that converge into the Mississippi, a hub for industrial manufacturing that required access to the rivers and rail yards. Ten miles from Graceland, rough-and-tumble Frayser fell, as did much of Memphis, as did much of the country, under the long spell cast by The King.

Frayser flourished for decades. In mid-century, the International Harvester plant employed more than 2,600 workers; the nearby Firestone plant and other industries brought more jobs. The area merged with the City of Memphis in 1958; schools and shopping centers proliferated. But by the late 1970s, the boom’s reverb was diminishing. “The men in my family worked at Firestone or Harvester, and the area was very blue-collar until the general collapse, when all the jobs disappeared,” says Cartwright. “When I was a kid it was like a small town complete with its own main drag, surrounded by more rural farmland on one side. The other side butted right up against downtown Memphis.” Frayser’s population began to decline rapidly after International Harvester eliminated twenty percent of its workforce in 1980. Another 850 jobs vanished from Harvester two years later, leaving the factory with half of the workforce it employed at its peak. In 1985, International Harvester laid off the remainder of its employees and shuttered the factory for good. Firestone, too, went dark. In Reagan’s America and well into the Clinton era, Frayser moved from middle-class stability to economic volatility.

For Cartwright, music soundtracked a humid and difficult, but oddly beguiling, town. “My dad had a large collection of records, and music was always on in the house so I was subliminally programmed from a very early age. I remember looking at records with inner sleeves and reading all the lyrics. When I was 11 or so I began writing poems and arranging them to look like inner sleeves. Then, when I was about 12 or 13, I caught the bug to play guitar. I had some of my own records and had access to all of my dad’s records.” The Cartwright family listened to the radio on Sundays while they cleaned the house, dad too busy dusting and vacuuming to bother with the stereo. This was Cartwright’s radio time, when he discovered what others in town were hearing; lingering too is a memory of riding in the car with his dad. “It seems vaguely pivotal. He made his own cassette comps of his favorite tracks and artists. We were listening to a tape of Mick Ronson–era Bowie really loud because his car had no air conditioning. The windows were always down because it’s always hot in Memphis, and the music has to be loud to overpower the sound of warm air rushing around your head. I can’t put my finger on a song but I can point to that tape.”

Cartwright’s obsession with music began early. “When I was just six years old, I had a portable record player I’d take with me everywhere I went. I inherited all my uncle and aunt’s records that were at my grandmother’s house where I spent most of my summers. She gave me all of their 45s; there was a lot of oddball Memphis stuff in there that you wouldn’t hear on the radio anymore. There was just a lot of odd stuff in general in there.” Cartwright’s grandmother introduced him to the thrills and spills of yard sales and thrift shops, and such mining for gold became a lifetime obsession for him, but in Memphis the radio was his real education. “When I was a kid listening to oldies radio stations in Memphis you would hear Pop 100 things, but you would also hear local hits, like the Hombres’ ‘It’s A Gas‚’ or the Guilloteens’ ‘I Don’t Believe.’ Those kinds of songs were really cool and really local. But the way charts worked back then was so different. Local radio really could be local. Things were different.” As an early teen with one ear tuned to the garrulous and wholly unique history of Memphis music—from Sun, Stax, and American Sound Studios to obscure local unknowns, kids in basements and garages—and one ear tuned to the hardcore shows he felt obligated to attend at The Antenna, a punk club on Madison Avenue, Cartwright began to identify, and to identify with, his hometown.

“I feel really lucky to have grown up there because it’s such a musical place, and there are so many great types of music that started there, or came to fruition there, that were such a huge influence on me,” Cartwright says. “As soon as I discovered one thing that blew my mind, I discovered something else that blew my mind, and then it really blew my mind that it came from where I lived! It’s really an amazing thing. In the 1950s and ’60s, the recording industry was exploding, and everybody in Memphis was trying to do it, and not feeling like they really had to conform a whole lot to anything in particular. You could just get lucky with any combination. You could totally make something in a budget studio, and if the right DJs played it, and if some other DJ heard it and played it out of town, you could go from a regional to a national chart hit. And so people are throwing all these crazy things against the wall, you know? They’re not attempting to sound cosmopolitan or anything, they sound like redneck people singing soul songs.”

He laughs affectionately, as much at the silliness of the statement as at the truths it embodies. “There were no limitations. And everything’s kind of blending together in this way. I get the feeling that probably a lot of regional artists feel the same way about their town. I feel like I’m lucky because Memphis was such a music town that it probably happened even more, the idea that, ‘Hey man, the kid down the street has a hit record, I can fucking make a hit record!’ There was so much of that.

“In the 1970s and 80s, after Memphis was in its decline, no one had any expectations of what you had to sound like in a band, but everybody understood the references, the Memphis references. So it was a great place to find my way as a musician. What if I’d been living in New York, or Seattle, or one of those types of places at that time? I would’ve felt more expectation to conform to gain popularity, but in Memphis everybody knew you were never going to be popular, so you didn’t have that kind of pressure to do something that would put you over the top or garner a larger audience.” The economics of the depressed city all but ensured that working musicians in the 1980s and ’90s weren’t going to pocket a lot of dough anyway. “It made it a little bit easier to follow your own path.”

An avid and committed record collector, with thousands of 45s and LPs in his possession, Cartwright can, by ear, identify a record made by Memphians. “At one point I think Memphis had more independent small labels than any other place in the country,” he marvels. “When I’m out hunting, sometimes I’ll find a record where there’s no address, a small-label thing. Even though there’s no information that tells me, or a publishing company that I can connect to something I know, I know when I hear a Memphis record. I can just feel it.” He adds, laughing: “Nine times out of ten I’m right, and in that ten percent where I’m wrong, it’s probably from Arkansas. It came from somewhere very close by!”

Cartwright’s history in bands is vast and eclectic, a testament to his tireless energy, his craftsman’s work ethic, and his love of playing live and with others. His first stable group was Compulsive Gamblers. Formed in the early 1990s with friend and partner Jack Yarber soon after Cartwright graduated high school, Compulsive Gamblers featured violins and fiddles and the occasional saxophone in addition to Cartwright’s and Yarber’s lo-fi guitars. The band released four singles before disbanding, unable to stay together after a couple of band members defected.

In the tradition of the Ramones, Cartwright and Yarber swiftly adopted the surname Oblivian and formed a band of the same name: the Oblivians played primal garage punk and became widely influential on the scene and the darlings of indie labels Crypt, In the Red, Sympathy For The Record Industry, and Estrus; sonic wanderers like so many indie punk bands, the Oblivians released material with each of these labels (and others). With Cartwright and Yarber on guitar and Eric Oblivian (pseudonym for Eric Friedl) on drums—the men circulated instruments among themselves, though never a bass guitar—the band pounded and snarled their way through dozens of singles, EPs, and albums (including a 2013 reunion). The songs Cartwright wrote for the Oblivians were generally beery and loud and snotty, and funny, but the decibel levels masked a songwriter with melancholy and melodies to spare.

When the Oblivians split up in 1997, Cartwright and Yarber, retaining their surnames, re-formed Compulsive Gamblers and released two albums, both more muscular and melodic than earlier Gamblers material, and more complex emotionally than the primitive rawk of the Oblivians. Among album releases, national and international touring, and bleary-eyed soundchecks, Cartwright would meet his wife, Esther; they’re raising three children, Andrew, Alex, and Ruby. He’s worked as a cook, a salesman, an electrician, has owned and operated a record store, done landscaping, toiled at many nameless jobs using his hands that would rather be holding a guitar. (“I’ve tried my hand at everything that seemed reasonable for a traveling musician, and even a few that were clearly not. The most likely influence of any of these was my stint working at a bookstore. Not so much because of the books but because of the people who buy books. Or steal them.”) This version of Compulsive Gamblers also fell apart—before the second album was released—and in the early 2000s Cartwright, following a stint playing too far from home in Toronto’s rootsy Deadly Snakes, began jamming with a handful of Memphis-area musicians, working his way through new material that was vastly different from his earlier bands. After a few lineups came and went, including one briefly featuring Melissa Dunn, niece of famed Stax house musician and Booker T. and the MGs bassist Donald “Duck” Dunn, Cartwright settled in with a quartet.

He dubbed them Reigning Sound. Their debut seven-inch EP was released on Sympathy For The Record Industry in 2000. Cartwright’s songwriting had found its truest and sturdiest home.

From Stanley Booth’s Rythm Oil:

“Dan [Penn],” I said, “what is it about Memphis?”

“It ain’t Memphis,” he said. “It’s the south.”

“Well, what is it about the South?”

“People down here don’t let nobody tell them what to do.”

“But how does it happen that they know what to do?”

He twirled the ukulele by the neck, played two chords, and squinted at me across the desk. “I ain’t any explanation for it,” he said.

This small exchange, casual and epochal, has been passed around by many since its first appearance in a piece Booth wrote in 1966, and was also quoted in Peter Guralnick’s indispensable history of Southern R&B music Sweet Soul Music. It captures something essential about Memphis: the tension between result and process, which is to say between light and dark, which is to say between surprise and mystery. For years, Cartwright has been writing songs of love and loss, pleasures and regrets, that respond to his hometown and its particular alchemy of independent spirit and craft. “I continue to be influenced by the place I grew up and all the music that came out of it,” he says, “as well as all the strains that passed through it, and were subsequently absorbed or evolved there. Especially all the ones that managed to slip through the cracks or were forgotten. They mean a great deal to me in a way I can’t explain. They have great qualities, but they go unnoticed and unloved. Somebody’s gotta love the orphans, and maybe they have to love a little more.”

Robert Gordon, author of a celebrated biography of Muddy Waters, a history of Stax Records, as well as It Came From Memphis—a boisterous cultural history of the city—considers Cartwright’s career as echoing the diversity of artists and styles he grew up listening to on the radio. “The part of Memphis I hear in Greg’s music is the end of the great AM radio days,” Gordon says. “We had two great pop stations that played black and white hits, and two great black-oriented stations. In the ’70s I’d sometimes tune into FM if they were broadcasting a local concert I was interested in, but it was past 1975 before my preference became FM. AM had that great sense of pop brevity in its songs. They’d hit-and-run. Didn’t like what you heard? Hang around for the next one. It would go from Beatles or Stones—the most popular of musics, to Motown and Stax to Detroit and Philadelphia and the UK, to the oddity and glam—it just kept coming. AM was dedicated to the most popular music, but Memphis AM had a very serious commitment to diversity, with a foot firmly in the Memphis scene. On all four of the stations. There were more than four, but it seemed to me like only four. I feel like you get some of that in [Reigning Sound’s second album] Time Bomb High School, in particular.

“And Greg is a serious record hound. When he had his own record store here”— Legba, which Cartwright eventually sold to Friedl, who renamed it Goner Records after the label he owns—“it may have been ostensibly about him making money in a business, but I think the true purpose was for him to hope that every record that was ever made would come through and that he would have the chance to play all of them from behind the counter. And short of that, at least the best ones would come through and he’d dive into those. It was research, in other words, and pleasure. And it happened to pay and to come with a rehearsal space in the back. Kind of ideal.”

Gordon notes that Cartwright hails from a part of Memphis that produced many garage bands and great guitarists, “so there was a path he could follow. What’s great is that, on that path, he blazed his own trail. He updated the sounds, often by tweaking retro sounds, imbued the music with his own personality, like all good artists do, and he found a supportive crowd—here at home, sort of rippling out from Midtown, to the wider region and soon enough nationally.”

Gordon adds: “I saw him DJ a party once, and it was quite like listening to a great AM radio show. It was all over the place. And all exciting.”

Photo: Jake Thomas

“If Greg was alive and writing in the early sixties, I don’t think he’d have any problems getting an office with a window in the Brill Building.”

— Mikey Post, Reigning Sound drummer

Two Sides To Every Man, Reigning Sound’s debut 7-inch EP, surprised fans who were expecting the raucous garage punk of the Oblivians. Cartwright was conscious of expectations and, anxious to progress from two-chord din, presented his new songs as a sampler for Reigning Sound’s debut album, Break Up . . . Break Down, released on Sympathy For The Record Industry in 2001.

Cartwright’s saying, Look, you’re as likely to find the Everly Brothers and Harry Nilsson in my records as The Cramps and the Misfits. The EP’s three songs inadvertently laid out the major styles that Cartwright explores in Reigning Sound. The A-side is “Here Without You,” a haunting, mostly acoustic cover of a song from the Byrds’ 1965 debut Mr. Tambourine Man; the B-side features two Cartwright originals, “West Texas Sound,” a hoarsely sung, driving garage stomp that he’d previously recorded with Deadly Snakes—less a song than an extended grunt—and “Pretty Girl,” a casually exultant beat ballad with a chorus that scores an epiphany. The latter tells the story of an ordinary moment: a guy leaves a party with his girl; fumbling for his keys in the dark, he turns as she kisses him on the cheek, and he’s rendered speechless by the simple gesture and her beauty, a beauty he knew but never felt so strongly. Like Tom Petty in “Here Comes My Girl,” Cartwright half-sings/half-talks his verses about the quotidian stuff—arriving somewhere, departing that place—until, struck and startled, his chorus (“Sha la la la la la lee, the pretty girl’s with me”) bursts through the routine with lyric color: the barely articulated surprise that a melody gives, or scores, or makes.

Joe King Carrasco once said, perhaps half-jokingly, perhaps in deadly earnest, that all he aspired to in his career was to write a song as good as ? and the Mysterians’ “96 Tears.” I ask Cartwright if there’s a song out there that he considers such an achievement, as something to aspire to. “For a rock and roll song, I hold Danny Burk and the Invaders’ ‘Ain’t Going Nowhere’ in pretty high esteem. It’s a Memphis record from ’66 or so but the vocal is super snotty and punk and the riff is so hypnotic that it almost resembles something from the first Suicide LP. It’s a sound and an idea that really inspires me to make something equally powerful. I also really like ‘That’s Alright By Me’ by Gene Clark. It’s a late track for him but just as good as anything he ever wrote. It’s definitely a vibe I shoot for sometimes, or at least a measuring stick for me as a writer.”

A slab of homegrown hysteria, “Ain’t Going Nowhere,” was produced by Sun Records guitarist Roland Janes at his own Sonic Studio, and released on his ARA label in 1966. It’s a brief and frantic 12-bar blues, Jimmie Crawford’s lead guitar bravely channeling Link Wray, drummer Eddie Sheridan’s drums forging the rocky shore into which the whole thing, made of adolescent nerve, threatens to crash-land. Clark, a founding member of The Byrds, wrote and recorded “That’s Alright By Me” sometime in the late 1960s after he’d left the seminal band, but the song wasn’t released until after his death in 1991. Using an early Johnny Cash spirit in its plucked acoustic, Clark’s sing-along marries loss with acceptance (“I know you think you must go, that’s alright with me”), though underneath that melody there are some anxieties. A salient line in the first verse must have struck Cartwright the first time he heard it: “my sensitivity is dying.” Obscure ’60s garage rock, and a folky, acoustic-band gem from a singer-songwriter. Ends of the sonic spectrum. What’s in between except everything?

Here’s a parlor game: try and distinguish Reigning Sound’s cover songs from Cartwright’s originals. There are usually two or three songs from other artists on each Reigning Sound album, historical templates, spirit cousins to the tunes that surround them. From the Beach Boys, the Everly Brothers, Carl Perkins, and Sam and Dave to the Guilloteens, the Carpetbaggers, Glass Sun, and Flash & the Memphis Casuals, Cartwright’s covers range over the sonic map, touching on popular and obscure acts, nationally known and locally incubated. “What attracted me to Reigning Sound wasn’t the original stuff but their and Greg’s take on the Memphis ’60s garage covers they did,” says Ron Hall, Memphis music historian, record collector, and author of Playing for a Piece of the Door: A History of Garage and Frat Bands in Memphis, 1960–1975. “I was blown away by ‘Don’t Send Me No Flowers,’ ‘Stormy Weather,’ ‘I Don’t Believe,’ ‘Brown Paper Sack.’ They blended so well with the original stuff, many younger fans here thought they were original.” He adds, “You have to be careful with a good songwriter like Greg, to overpraise the covers as opposed to his own stuff. But Greg seemed to enjoy the fact that I loved the stuff.”

A record dealer in Memphis for more than thirty years, Hall has known Cartwright for a long time. (He discovered later that he and Cartwright’s dad attended the same high school.) Hall feels that, having grown up in Frayser, Cartwright had a different kind of exposure to the “Memphis vibe” than kids who grow up in the Midtown area. “To be frank, it was more of a redneck area so he was probably exposed to heavier rock sounds. His knowledge of the soul stuff is far better than my own. He went beyond who the artists were, he researched writers, producers, studios, wanting to know where the effects, warmth, vibe came from. I remember one night him coming to my house with a batch of records and him having cool West Tennessee bands I hadn’t heard, but also knowing about small studios in the area where obscure soul stuff was cut.

“I was impressed by his passion to know about each record. I miss that.

Greil Marcus, from his recent book The History of Rock ‘n’ Roll in Ten Songs: “Regardless of who writes it, no successful song is a memoir, a news story, and no such song does exactly what its author—and that can be the writer, the singer, the accompanist, the producer—wants it to do. One must draw on whatever new social energies and new ideas are in the air—energies and ideas that are sparking the artist, with or without his or her knowledge, with or without his or her consent, to make greater demands on life than he or she has ever made before.” He continues: “That is true for the songwriter; it’s true for the singer. The song, as Louise Brooks liked to quote ‘an old dictionary’ on the novel, ‘is a subjective epic composition in which the author begs leave to treat the world according to his point of view,’ but the song, as it takes shape, makes certain things rhythmically true and others false, makes certain phrases believable and others phony—and someone speaking to the world by himself or herself is never solely that. Other voices, those of one’s family and musical ancestors, other singers competing on the charts, movie characters, poets, historical figures, present-day political actors, are part of the cast any good song calls up, and calls upon.” Marcus is describing the long, enigmatic route between experience and expression, between the “I” and the “We.” Cartwright may be writing from the storehouse of lived experiences, of living people with whom he relates and collides, but those experiences, those real people, assume an abstracted, generalized shape, become silhouettes into which the listener can step and see that she fits.

“He’s rooted in tradition without being slavish about it,” says Alex Greene, guitarist and organist in Reigning Sound from its inception to 2004. “He can evoke decades of songcraft, but steers clear of obvious clichés. One thing I appreciate is that there is a literary quality to the characters, images, settings, but he avoids the overly wordy writing of, say, Elvis Costello. He’s more like Joe South. Smart, but earthy.” Mikey Post: “What separates Greg from the pack is that every song he writes tells a story. There’s a clear picture painted in every lyric. He doesn’t make you wade through a bunch of flowery nonsense to get to the heart of the story. It’s also the subject matter—love lost, love found, and all the joy and misery it brings. Everyone’s been in love, and lost love in some way or another, so it’s very easy to relate to his songs.” Larry Hardy, head of In the Red, a Los Angeles–based label that has issued several Reigning Sound records, notes, “One thing I’ve always been impressed with in Greg’s songwriting and delivery is his ability to write lyrics that are pretty emotional and vulnerable yet the way he sings it is completely powerful and energetic. He’s written lyrics that are so sad and melancholy that they can move me to tears under the right circumstances, like after a bad break-up, but the way he sings them is so soulful and strong.” Greene: “A big draw for me is Greg’s voice. There are so many varieties of affected singing out there in the indie-rock world that it was a tremendous asset, in my mind, to be working with an unaffected soul-slash-rock-slash-country singer. There is a great honesty in his voice. It’s hard to come by these days.”

“I mostly sing about the obstacles of being content,” Cartwright tells me. “Not because I want to wallow in them but because they are universal subjects of meditation. Even joy itself is bittersweet at times. People immediately connect with that struggle.” He adds, “Happy people don’t need you to say you understand. As an artist I don’t have much to say to happy people. And that works out great because they’re busy being content. For the rest of us, coming to terms with rejection, failure, death, and the fragility of love is very important. Some people are self-conscious about these things and maybe they don’t want to talk about them, but sometimes it just feels good to know you’re not alone. Books and music do this better than possibly anything else.” Cartwright acknowledges that he can’t write outside of what he knows, “not convincingly. Everything I write about is either about me or something that happened to someone I’m really close to. For the most part it has to be something that happened to me, something I’ve thought about a lot, or something I’ve felt. Most of it is things that have happened to me. Life gives you plenty of fodder for being sad.”

“When you make a big mistake, it never leaves your mind completely,” he said to Austin Ray. “It’s always there to reflect on, especially when the sensation comes around to make the same mistake again and you think you’ll get a different outcome. I’ve always got several strings of thought going on when I try to write songs. I could be thinking about something that happened to me, or a friend, twenty years ago, and also thinking about some conversation or gossip I heard in a bar. It’s all those things converging, where, in a way, you jump from one to the other, and you can tell a story that seems real. I’m all for that. That’s an aesthetic I strive for—something that’s emotional but also crafted, at the same time, to be a good pop song.”

During our conversation, Cartwright considers something, and then laughs loudly. “A lot people say to me, ‘Boy, you’re writing all these really sad songs, you must have a really horrible relationship with your wife.’ No, no, no, no! In fact, I found that not until I got into a really good head space and was in a relationship where I felt really good about myself that I was able to write sad songs that I felt could really connect with people.” He said to John Jurgenson, “I can write a handful of party songs, but I can’t fill up an album with them. For whatever reason, the thing that I return to are the sad songs. Doing the sad songs allows me to be happy.”

The paradox? “When everything goes wrong, love won’t leave you a song,” Cartwright laments on 2009’s aptly titled Love And Curses. “And no blue melody could ever please me.”

He’d begun seeing Esther, and he wanted to write something to say to her how happy he was. “I’d been in limbo for a while, not really understanding what it was really about to be in love with somebody, and that somebody can help you. They can be kind to you, and you can be kind back to them, and it’s such a wonderful thing. It’s basically saying thank you for this experience.”

He’s describing “I’m So Thankful,” a stirringly carnal song from Break Up . . . Break Down. The album is moody and despondent—check the title—quiet, downbeat, no rockers, an album that Alex Greene said “really captured the sadness of living in Memphis, more than any other record except perhaps Big Star.” The closing song, bruised by all that’s come before (“I Don’t Care,” “Goodbye,” “So Goes Love,” “So Sad”), sounds at first weary, defeated, until Cartwright begins to sing, and the bitterness you thought you heard turns out to have been something else, filled with desire. The performance by the band—Cartwright on guitars, Greene on organ, Jeremy Scott on bass, and Greg Roberson drumming—is stark, compact, and powerful, and recognizes that the chorus (“Let me show you how much tonight”) is so sensual that all they have to do is ride the offering. Beyond Cartwright’s emotional, high-register vocal, the only drama in the playing emerges from the shadowy, urgent push of his guitar into the chorus—anything else would be too much, might turn this man’s passion into something aggressive, a display of testosterone for his benefit, not hers.

“I’m So Thankful” is one of indie rock and roll’s great love songs. Every time I listen to it, I picture Elvis on the other side of the studio, ghostly, singing “Power Of My Love,” from 1969. The correspondence is not unlikely: Reigning Sound recorded many of their albums, including Break Up . . . Break Down, at Doug Easley’s and Davis McCain’s Easley-McCain Studio, a nondescript, two-floor, square building in east Memphis on Deadrick Avenue on a dead-end road near a Walgreens and an AutoZone. The setting is unremarkable, but the musical history of the building is pronounced. (It was harmed by fire in 2005, and shuttered; in 2009 it was re-born at another location.) Built in 1967 and known as Onyx (now as American East), the structure was the first in Memphis to be purpose-built as a music studio. It was conceived by businessman Don Crews who’d been partnered with Chips Moman at the legendary American Sound Studio where over a hundred hits were recorded by, among others, Bobby Womack, B. J. Thomas, Dusty Springfield, The Box Tops, Joe Tex, Neil Diamond, and Aretha Franklin, and where Presley—riding his fabled “comeback”—cut “Power Of My Love.” Before forming American Sound, Chips Moman was an engineer and producer at the Stax studio. Follow the line on the map: Stax to Moman to American to Crews to Onyx to McCain-Easley. The cultural and aesthetic lineage winding its way to the back room in a tiny building on Deadrick Avenue startles.

In 1990, Easley and McCain moved into Onyx, re-made it, and re-named it, ushering in an analog renaissance era for local and out-of-town punk and indie bands, recording in addition to Reigning Sound, the Grifters, Sonic Youth, Pavement, the White Stripes, and many others. Easley and McCain set up shop the same year that American Sound Studios was razed and replaced by a parking lot. “It had water damage, and termites had totally eaten the control room out. It was in really bad shape,” McCain says.

“Power Of My Love” is almost too much: too swaggering, too cocky, the dubbed-on female vocalists’ soft-porn bordering on silly, yet the braggadocio is tempered by Presley’s half-grinning lived-in vocal, and by the superb, muscular ensemble playing, especially by Gene Chrisman, the American Studios house drummer who helps transform what could have been strutty boasting into visceral, sensual confirmation. The recording captures the excitement of the excitement going on in the room. The song was written by Bernie Baum, Bill Giant, and Florence Kaye who, collectively, or in pairs, were responsible for composing many songs from Presley’s Hollywood-era, including some solid tunes (“[You’re The] Devil In Disguise,” “Spinout”) and some groaners (“Poison Ivy League,” “Queenie Wahine’s Papaya”). Apparently having inhaled the same redemptive fumes Presley did in 1968, they produced “Power Of My Love,” a lascivious song that Presley could believe in, revel in, have fun with, not out of contractual obligation but out of genuine joy. His song swaggers and brags, Cartwright’s pledges and proposes, both originating in the body and in the body’s promises of pleasure and gratitude. Singing at McCain-Easley, on the cusp of a career helming a great American rock and roll band, did Cartwright see Elvis, Moman, and Crew among the many Memphis ghosts?

Photo: Kyle Dean Reinford

June 26, 2005. Reigning Sound is playing a set at Goner Records, the former site of Cartwright’s record store. Cartwright has recently left Memphis and settled in Asheville, North Carolina; a positive move for his growing family, but in other ways unsettling for the River City native and devotee. The band is supporting their most recent album (their third, following 2002’s lively and rocking Time Bomb High School), a brutally loud record called, naturally, Too Much Guitar. The album was created by default: a clutch of quieter, more folk-rock songs had been laid down and mixed at Easley-McCain, but when guitarist and organist Alex Greene subsequently left the band to devote time to his growing family, Reigning Sound, reduced to a power trio, headed back to the studio, compelled to re-record the songs that had been reliant on Greene’s moody, subtle playing.

One tune, “If You Can’t Give Me Everything,” was utterly transformed in the process, greedily exchanging downers for uppers. What began as a muted, Velvet Underground–styled kiss-off was amped up into a litany of vicious, desperate demands—“Get your foot out of my door!”—the chord changes moving from sleepy to torturous. You’re surprised that it’s the same song, yet you still believe each was written by a different man. (Cartwright: “Doug Easley said, ‘I liked it better when you were playing it slow.’ And I said, ‘Maybe you’re right. Let’s go back in and cut it, and slow it down to where it was.’ The intended release was the slower version.” These original quieter tracks were compiled, with several other stray songs, on Home For Orphans, released in 2005; a single from these sessions, “I’ll Cry” backed with “Your Love,” was released that same year.)

At Goner, some of the voltage is still sparking. Near the end of the set, Cartwright launches into “Two Thieves,” a song he’d written while in Compulsive Gamblers, the final track on the Gamblers’ final album (2000’s Crystal Gazing Luck Amazing). A threnody for two of Cartwright’s friends who’d died from substance abuse, “Two Thieves” moves among affection and disappointment, grief and frustration, and provides a chorus that’s the very embodiment of sighing bittersweetness: If the two of you had met, both your mothers would have wept—two peas in a pod, or just two thieves on the nod. On the Gamblers’ recorded version, Cartwright’s voice is weary, unaffected; he’s singing from the inside of discovery, and the discoveries are somehow both unhappy and celebratory. The band—Cartwright (Oblivian) and Dale Beavers on guitars; Jack Oblivian on drums; Brendan Lee Spengler on organ; Jeff Meier on bass—falls into, or it’s more accurate to say that the song begins in the middle of, a Dylan/ Band “Big Pink” murky mood; the musicians are tired-sounding, but alert, open to the possibilities of the newness of grief. The song’s almost too painful to hear. In an exquisite, exhausted vocal that competes with a devastating slide guitar and pushes against his top register, moving with and knocking against the simple melody and transcendent changes, despondent, searching for the shape of the melody will make, Cartwright universalizes his experience with friends and lovers who are reckless and beyond our help. “Two Thieves” is one of Cartwright’s most personal songs, and one of his greatest.

Wearing black boots, black slacks, and a black T-shirt, Cartwright plays backed-up against CD bins and band posters, standing just a few feet in front of the patrons who’ve come to Goner Records to see him and the latest Reigning Sound lineup (David Wayne Gay on bass, Lance Wille on drums). They get through the first verse and the chorus of “Two Thieves,” played at an oddly brighter pace than the original, as if the band is willfully avoiding the song’s sorrowful pull. Cartwright sounds distracted as he starts the second verse; he’s pulled out of the song. And he abruptly ends it: “Hold on, I gotta stop,” he says. “I’m getting electrocuted like hell. I don’t know what it is …” Someone off-mike suggests that it must have something to do with the ground. A moment later, stepping to the front, chuckling, Cartwright says, “And with that we’ll change mood,” and launches his band into the snarling anti-anthem “We Repel Each Other” from Too Much Guitar.

Too much. Cartwright, a formalist wrestling with the bedlam of grief. In Robert Gordon’s It Came From Memphis, local legend Jim Dickinson says, “Memphis is about making chaos out of seeming order.” In another world, poet Adrienne Rich: “In those years formalism was part of the strategy—like asbestos gloves, it allowed me to handle materials I couldn’t pick up barehanded.” I’m getting electrocuted like hell.

For years, virtually every day, Cartwright wrote out in his garage, on his acoustic, playing with chords, waiting to see what corner the next change would turn, what was there, always letting the music lead him to discover what he felt like talking about. Eventually, life broadened, deepened, became more complex. After the move to North Carolina, his teenage son took over the garage as a place to store his stuff, hang out, forge his own environment, as kids must do, and the house’s sunny front room became Cartwright’s workshop. “It’s kind of apart from the rest of the house, so I get a little bit of privacy. If I have a day free and all the kids are at school I’ll get out the four-track and sit and work on melodies and record things so I can have them to listen to later, try and work on them, push them a little bit further. Work out melodies and lyrics.” His albums and 45s and music biographies are crammed into the front room, which is a plus: “If I want to take a break, listen to something, or if I have an idea that I’m working on and it pops in my head, like, What would be something that would be a nice signpost of where this should go? I can listen to it and it might inspire me.” Once—if—he gets something going with two or three chords, he’ll start humming a melody. “And once I have a melody line going then I know what the lyrics should maybe do. Not necessarily what they should say, but at least what they should do.”

I ask him what he means. “Once you come up with a melody, you can play that melody with any instrument, right? You can hum it, or you can sing it, or you can play it with a guitar, or a flute, or whatever. So you know what that melody’s gonna do, but that doesn’t mean with a vocal that you have to fill up all that space. You can either say a lot or say a little. You can fill it up with ideas or you can make it very simple, or …I don’t even know how to say it.” Here he pauses, trying to explain a mystery to himself. “Once you understand how the melody should work, then you start to tweak the melody and figure out if you have a rapid-fire type of lyric or if the lyric is kind of lazy or if the lyric is gonna be behind the beat with the melody. Once you understand the chord arrangement and the melody, then you kind of get into the nuances of what the vocal is gonna do. I might even graduate from humming something to actually singing something, just so I can see how the words set, you know, if the words should be long, or short, or how they twist around the melody. Those words may not stay at all. Sometimes they work out to where I actually use them, and sometimes I realize, Okay I like the way this works, but this is not what I want to talk about.”

Then what? “Well, it’s funny. I can sit down and be in the mind to write one kind of song and play a couple chords and kinda get something going and then realize, No, I don’t think a major chord is going to work here, I think I need a minor 7th here. And then I realize, Oh, I’m not in the mood to write that kind of song at all, I’m in the mood to write this kind of song. Once you get the juices flowing you never know what might pop out, because what your mood is right that minute might or might not reflect in the song you write. I could be just as content as can be and write something very melancholy. Sometimes it’s even easier.”

What does a minor chord do for you? “I love minor chords. They can be powerful and triumphant and lonely all at the same time.”

In his twenties, serious about his craft, Cartwright faced a dilemma shared by many songwriters, post-1977: is there space for me in the anti-melody mayhem of punk rock, post-punk, and hardcore?

He felt the tensions early. “The first time I wrote a band name across the back of my jacket I was imitating what punk kids were doing, but I didn’t know what punk really was yet, or who those bands were,” he admits. “I thought you were just supposed to exclaim your love for an artist that other people didn’t know or like or talk about. So I went to school with a jacket that said ‘Nilsson’ across the back. At the time, my dad was the only adult in my sphere who listened to his records so it seemed very personal.” Cartwright felt and heard a certain punk attitude in the maverick Harry Nilsson—“There was something very dark there”—even if he couldn’t name it. “The albums, they were really strange. Kind of quote-unquote punk, but pretty. I remember reaching my teenage years and listening to that song: [sings] ‘You’re breaking my heart, you’re tearing it apart, so fuck you!’ To a kid, you’re just going, ‘Yeahhh! Curse words!’” When Cartwright grew up and listened to hardcore punk records, he felt “a little silly for equating my hero with this scene, but at least no one at my school could laugh at me, because they didn’t even know what or who he was anyway.”

Cartwright dutifully attended shows at The Antenna, but felt a bit like an outsider, acutely feeling the distance from his friends and peers who were punk and hardcore disciples. “That was a problem for me when I was in my early teens, and I started meeting people in high school who were into rock and roll,” he admits. “I found out pretty quickly that they were into things I didn’t know anything about. They were into hardcore and things that musically didn’t really make any sense, stuff that was played so fast and with such abandonment of any concept of melody. I said to myself, I don’t really understand this, but I’m gonna go to shows. And I’m not gonna pretend that I didn’t understand some of it and that I didn’t like some of it, but for the most part I didn’t get it. I tried and I tried.”

The bands and artists he did respond to were groups like The Cramps, Tav Falco’s Panther Burns, Gun Club, the Misfits, “things based on things that I understand and that I like. These people have figured out a way to put a new spin on all these traditional forms. And that is what I’m built for, because I can’t do the other things. My heart really wouldn’t be in it. I wouldn’t know how to do it earnestly because I don’t understand it. And that’s not to say it isn’t good, it just didn’t click with me.”

Doug Easley, whose partner Davis McCain was for years the soundman at The Antenna, has a wide-angle take on many young Memphians’ attitude toward punk rock, an outlook that’s steeped in the tradition and history of the city. “It seemed like Memphis punk happened, but the musicians couldn’t really reject what had happened musically because they actually liked the past. Sometimes I think it’s like Memphis was pissed because the rug got pulled out from under them when things died. We played the old songs in a new fucked-up way.

“Gotta stay current? Yeah, right.”

Speaking with writer Fred Mills a decade ago, Cartwright observed that because his albums had remained under the radar, he hadn’t had to deal with wide attention. “That keeps things right where I like it: I sell enough records so that whoever puts my record out will let me do whatever I want, but not so much attention that a major label would sign me to a contract where I have to do what they want me to do.”

Cartwright has tasted some measure of conventional commercial success, most tantalizingly in 2007 writing songs for, co-producing, and playing on former Shangri-Las singer Mary Weiss’s comeback album on Norton Records, Dangerous Game, a release that garnered positive reviews in major places (and landed an anxious Cartwright and band backing Weiss on Conan O’Brien’s Late Night. “All these people asked me, ‘Why were you wearing sunglasses? Were you trying to look cool?’ And I reply, ‘No. I was just so nervous. I needed something in between me and everything else’.”) But Norton, too, is a small enterprise run by devoted but cashstrapped owners. Happily loyal to indie labels, Cartwright has had to weather problems endemic to them, such as poor distribution and limited recording and promotional budgets. Larry Hardy, whose label In the Red released Time Bomb High School, Too Much Guitar, and Love And Curses, was pleased with Reigning Sound’s sales figures. “Their records sold well, by my label’s standards, anyway. It depends on how you define conventional success. Greg’s not really the sort of guy who is willing to go out and do a lot of the bullshit song and dance you have to do to get to that quote-unquote next level. I think it would sicken him to deal with that. I’d hope that he feels he’s achieved success already. He has a lot of fans, respect amongst his peers, and he’s doing his music for a living.” He adds, “I think Greg’s music ranks him alongside all the greats who came out of Memphis. He’s incredibly successful in my eyes.”

In 2014, Reigning Sound signed with Merge, a major independent label that has scored commercial hits with Arcade Fire, Spoon, and She & Him, and has issued critically celebrated, influential albums by Neutral Milk Hotel, Magnetic Fields, M. Ward, and others. Released in the summer of 2014, Shattered—recorded in Brooklyn, New York, mixed by old family hands down at Easley-McCain—features a new Reigning Sound lineup, with Post on drums, Benny Trokan on bass, Mike Catanese on guitar, and Dave Amels on organ (those four also play, sans Cartwright, as The Jay Vons). The bulk of Cartwright’s songs on Shattered—there’s one cover, Garand Hilton’s smoothly aggressive “Baby, It’s Too Late”—lean heavily into Memphis’s long, warm R & B and soul shadows, generally in the band’s take on the Stax sound, and particularly in how they evoke the taut, economical, and expressive ensemble playing of Booker T. and the MGs. (The Stax band has long been a touchstone for Reigning Sound; original organist Alex Greene remembers telling himself, “‘Okay, I’m going to pretend that I’m Booker T. moonlighting in a folk rock group.’ I love Booker T. Jones’s simplicity and sheer grooviness.”) New songs like “In My Dreams,” “I’m Trying (To Be the Man You Need),” and “Starting New” mine the effortless-yet-urgent, every-note-counts arrangements of the Stax sound, collapsing emotional turbulence and romantic chaos into charts and changes, the whole thing a melodic balance of passion and decorum. Other songs touch on sleek, ’70s soul call-and-response grooves, rustic country strings, and rootsy pop.

Listen to “I’m Trying.” It’s a song I desperately wish I could hear Sam and Dave sing in some alternate universe, trading lines and pridefully exhorting each other. You half expect Cartwright to drop in a spoken section during the guitar solo—a clichéd arrangement would insist on it, and Amels gives the singer the organ-spotlight—but such a move would be corny here. Better to evoke the past, to let familiar notes and moods and arguments fill the empty spaces as Cartwright and his band go on singing and playing. Remember the young couple in “Pretty Girl”? That epiphany didn’t take; they rarely do. The revelation of a kiss and the rush of her beauty faded—the next morning, in line with all of the others after it, and the days pile up, dragging regrets and responsibilities and all kinds of adult noise behind them. All caught up on the things I said I’d do, If I don’t pay enough attention to you, just know I’m trying to be the man you need. The “sha la la la la la lee” that in an earlier time sang of surprise and gratitude, is now gibberish from someone else’s life. What’s the currency of a kiss on the cheek in the dark? Got no money or fancy clothes, but a true, true heart, I’ve got one of those. He’s trying.

Chicago’s Empty Bottle, on another occasion. I’m waiting again for Greg Cartwright to hit the stage. This time I know who he is. The opening band, the third opening band, is playing for a long time, their generic psychedelia and extended guitar solos casting a pall (over me, anyway). I turn to look past my shoulder to gauge the size of the crowd— it’s packed—and there’s Cartwright standing behind me, towered over by Dave Amels. Too shy to introduce myself, I turn away but not before I register a look on Cartwright’s face of impatience blended with politeness. He wants to get onstage; he wants to sing. I wonder what he’s thinking: The opening song? A 45 he scored at Salvation Army that afternoon? Some girl? He wants to go on and let loose his changes, let them please and surprise him and us again. He wants to sing. And now I picture him in dad’s car. David Bowie’s Aladdin Sane or Pin Ups is playing, all of the windows are down, and outside in Tennessee it’s so hot that the roads melt and the trees sob, that old story. Cartwright’s gone, wending his way among what the chords offer as promises, as surprises, as elevation or sinking, as stories in the air.

Many thanks to Rich Tupica.

Reigning Sound’s discography—like Compulsive Gamblers’ and the Oblivians’—is widely and enthusiastically spread among labels, and over albums, EPs, singles, split-singles, and various-artists compilations. Don’t be fooled by the gaps among the releases, because Cartwright’s always busy: he’s contributed as a writer, performer, and/or producer to many bands during Reigning Sound’s existence, including the Detroit Cobras, the Reatards, The Cuts, the Horrors, and Mr. Airplane Man. In addition to Mary Weiss’s Dangerous Game in 2007, he wrote for, played on, and co-produced the Parting Gifts’ Strychnine Dandelion, released in 2010, and toured with them. In 2009, Cartwright released a solo acoustic album on Dusty Medical Records, Live At Circle A (“Recorded live at the Circle A, Milwaukee WI, March 26, 2006, at 2 o’clock in the afternoon”), which is highly recommended; his voice sounds ageless.

Reigning Sound’s family tree has roots that go back decades. Though separated by a dozen years, Break Up…Break Down and Shattered are cousins in sound, performance, and vibe; on the other side of the family, Time Bomb High School and Love And Curses are sonically related. Too Much Guitar is the black sheep: loud, rancorous, rude, impossible to ignore, the family member who everyone secretly hopes shows up at the reunions. Here’s a selected discography:

Albums

Break Up . . . Break Down (Sympathy For The Record Industry, 2001)

Time Bomb High School (In the Red, 2002)

Too Much Guitar (In the Red, 2004)

Home For Orphans (Sympathy For The Record Industry, 2005)

Live At Maxwell’s (Telstar, 2005)

Live At Goner Records (Goner, 2005)

Love And Curses (In the Red, 2009)

Shattered (Merge, 2014)

EPs

Two Sides To Every Man 7” (Sympathy For The Record Industry, 2000)

Abdication . . . For Your Love (Scion, 2011)

Singles

“If Christmas Can’t Bring You Home” (Norton, 2004)

“I’ll Cry” (Slovenly, 2005)

“Black Sheep” (Norton, 2006)

Notes

Unless noted, all quotations are from conversations with JB, September and October 2014. Some of my observations about Cartwright originated and were first published at No Such Thing As Was.

Information about the naming of Elvis Presley Boulevard from The Times-News (Hendersonville, North Carolina), June 9, 1971.

Information about Frayser, Tennessee’s history from Frayser: A Turning Point, Comprehensive Planning Studio, Fall 2006, Graduate Program in City and Regional Planning, University of Memphis.

“Seriously, if it weren’t for my wife . . . ,” Jordan Reyes, Delayed Gratification (2012).

“When I was just a six years old . . . ,” Rich Tupica, Turn It Down, 2009.

“When I was a kid listening to oldies radio . . . ,” David Bevan, Scion, Vol. 3, 2011.

For a solid overview of Compulsive Gamblers’ and the Oblivans’ histories and their place in the garage punk underground, see Eric Davidson’s terrific We Never Learn: The Gunk Punk Undergut, 1988–2001 (Backbeat, 2010).

Stanley Booth, Rythm Oil: A Journey through the Music of the American South (Vintage, 1993).

Information about Danny Burk and the Invaders’ “Ain’t Going Nowhere” from Ron Hall, Playing for a Piece of the Door: A History of Garage and Frat Bands in Memphis, 1960–1975 (Shangri-La, 2011).

Greil Marcus, The History of Rock ‘n’ Roll in Ten Songs (Yale, 2014).

“…not convincingly. Everything I write about…,” Tupica

“When you make a big mistake, it never leaves your mind completely,” Austin L. Ray, Creative Loafing, 2013.

“I can write a handful of party songs … ,” John Jurgenson, Wall Street Journal, June 26, 2014.

“It had water damage …,” Joe Boone, “The Easley-McCain Era: Two Memphis Engineers Influence the World,” Memphis Flyer, June 5, 2014.

“The albums, they were really strange … ,” Tupica.

“That keeps things right where I like it … ,” Fred Mills, Detroit Metro Times, 2004.

“All these people asked me …,” Ryan Leach, Bored Out, 2014.

Joe Bonomo was named the music columnist for The Normal School in 2012. His books include Field Recordings from the Inside, Sweat: The Story of The Fleshtones, America’s Garage Band, Jerry Lee Lewis: Lost and Found, AC/DC’s Highway to Hell (33 1/3 Series), Conversations With Greil Marcus, and, most recently, No Place I Would Rather Be: Roger Angell and a Life in Baseball Writing. He teaches at Northern Illinois University and appears online at No Such Thing As Was. Visit Joe on Twitter and on Instagram.