right here.

By car there’s only one way in: Take the county road due north until it dead-ends in our gravel driveway. Simple as that, we say, but folks don’t believe us sometimes. There must be something implausible or far too easy about a straight shot with no bends or turns, the only impediment a crooked stop sign we seasoned locals tend to ignore. The road doesn’t just end but extends into our driveway. Old maps show a line reaching up through what’s now our garage into the fruit orchard we planted years ago. Engineers once dreamed of a wider throughway, maybe a two-lane bridge spanning the river to the north. But now that we’re here—rooted into the soil, nestled into these woods for good—the threat of encroachment exists in the abstract only.

Two survey lines and an east-west crossroad further fix and legally bound an area shaped roughly like this:

What you see (turtle? umbrella? humpback whale?) is what you get, but people still get lost from time to time. On summer days we can tell by the crunch of hot tires on loose gravel, the breathless inertia of weekend voyagers stopped cold by navigation betrayal. When he was alive my father kept a stack of printed directions, handed them out with a reassuring smile. Now we just wave on approach to show we’re friendly and point back up the road. Most come here in search of “the other side,” but there’s only one way out and several ways around or through or over. “It really depends,” I offer supportively. Then a humble retreat and more crunching gravel. This turtle-umbrella is the end of the road for us, but for others it’s just the beginning.

Here’s another view from the family archive:

I’ve tried (in my head at least) and something always goes wrong between “intersection” and “small concrete bridge.” This is not so surprising in a post-GPS world. Every week I drive to and from the city for work, and all it takes is one freeway redirected or a new stoplight installed to see decades of “southwesterly direction” collapse into the soft chaos of outdated instruction. Continue straight ahead, by all means, but if you get lost that general store in _______ burned down years ago.

“We’re on the road!” we shouted in unison, hardwired to the moment when Dad steered the Chevy wagon off that final two-lane blacktop. As kids we could care less about left and right, forks and crossroads. Weekend trips to the farm started up there and ended right here, is all we needed to know. Fat strips of redacted time filled the emptiness in between.

the site of a tragedy.

Before cars, county roads, and stop signs; before smart phones, GPS, and fat strips of redacted time, the Reverend Adam Payne, traveling “New Light” preacher, departed on horseback from Plainfield, Illinois, riding generally in a southwesterly direction.

The year was 1832, but the article I’m reading was written by C. C. Tisler in 1938. Amateur historian and staff writer for the Daily Republican-Times, Tisler opens his July 1 “Ramblin’ Around” segment with a brief description of the verdant bottomland my great-grandfather had purchased the year before.

Then he tells a scary story.

Eighty-plus years separate my reading from Tisler’s writing; more than a century his writing from the event he describes. Two hundred years, more or less, and I’m here to report that the Reverend Payne, no stranger to the Illinois valley, “firmly believed the Indians would not kill him,” but kill him they did somewhere “on or near” the place I call home.

I don’t know why the good Reverend believed what he did. A large, imposing man with broad shoulders and a full gray beard, he may have assumed his impressive stature and noted gift for oratory would protect him from the Myaamia, Kiikaapoi, and Meskwaki farmers fighting back against decades of settler displacement.

He’d long since broken ties with the church but drew large crowds attracted to his booming voice and fierce evangelism. He was a devout Christian, an ordained Elder of the Schwarzenau Brethren. Raised in the Dunker (German Baptist) tradition, he was industrious, charitable, temptation-averse, and given to song. He despised the mean and refused to go to war. He was blameless in public and in private. He was hopeful of the imminent return of Christ. He was a godly man on horseback, and he was white.

None of this saved him from a “ghastly” fate.

The initial attack occurred somewhere northeast of Marseilles, Illinois. Then a chase ensued, driving the injured horse and rider farther west. When the horse fell dead, “Indians danced about the Rev. Payne whooping and yelling.”

Unarmed, the wounded man could not defend himself—or, quite possibly, the pacifist Payne decided not to. What he may have believed in those final moments is anyone’s guess, but the end came quickly. “A tomahawk was buried in his skull. Then his head was cut off and carried to the Indian village.”

The story would have ended there but for the arrival of a “degenerate half breed” named Mike Gerty. While no friend of Adam Payne, Gerty had “some respect” for the New Light preacher. Enraged by what he saw, he “grabbed a tomahawk” and set off in search of Payne’s assailants, but calmer moods prevailed, thus averting a second tragedy.

Gerty buried the severed head. A few days later Sheriff Walker buried the rest of Payne’s body on the open prairie, “possibly on what is now the Marsh property.” The Reverend’s belongings were mailed home to the grieving family. Among his possessions: a Bible, a spy glass, fifty dollars tucked into his coat pocket.

It’s a myth many years in the making, a special kind of ramblin’ indeed. A spot somewhere on or near the family farm was the end of the road for Reverend Payne, but for people like me it was just the beginning. My great-grandfather knew it, C. C. Tisler knew it, and now I know the moral of the story too: Land stolen then torn to pieces to be bought and sold can be reassembled to resemble a dead preacher whose buried body can’t find its head.

a garden of the mind.

Excavation had readied us, leveling the back slope to a flat expanse of hard-packed clay. The house was in, the kids on their way, so all we needed to make the land whole again was a truckload of compost, a few hand tools, a couple dozen long weekends, and two bodies in motion realizing an old dream peeled open to absorb the hot summer sun. We’d made a living as teachers and planners, organizers and thinkers, so in the fierce cold of winter and waiting out spring’s colossal downpours we got busy reading books, jotting notes, talking things through. Love was in the works and joy flooded our neural networks but sometimes frustration and a silly fondness for going negative threw jagged ego into selves otherwise firmly tipped toward going nowhere. We’d never done anything like this before. We had the advantages of location, resource, inspiration, and wherewithal, but sadly no book, website, or YouTube channel can tighten the bolts on two aging humanoids swapping feedback for the good of some pet project or untried idea. Friends and neighbors asked how it was going. All we could say was not yet but never not ever. We looked to dead grandparents and faded childhood memories to find answers to questions etched into our notebooks with fingers cramped from a full day’s raking and shoveling. We’d been given our instructions: Identify form elements (earth, water, air, heat); draw connections inside and outside the body; observe the living presence of all other beings (animal, vegetal, mineral); be aware at all times of bodily positions and movements (standing, kneeling, bending) especially when handling a chainsaw or hugging a chicken or pausing for a moment to parse the melody of nearby indigo bunting. In the beginning we favored hugel mounds—those marvels of permaculture design whose hulking shapes in the dense morning fog made our young garden look like a prairie graveyard. Somebody joked once about buried bodies but we just smiled and kept planting anyway. Years passed with the help of rain barrels, discount hoses, visiting relatives, our daily share of 430 quintillion Joules of solar energy, and finally, when the backs and joints started giving out, a new method to stave off hopelessness one of us potted over breakfast one morning as “simplify/amplify.” It’s like karma, almost, this never-ending concert of choreographed intention and purposive, consequential doing. But something in the bumpy contours of our shared aspirations kept us ever searching for a better way. Hugel conspired in the background by slow-baking all that compost, old hay, newspaper, oak leaves, and crumbled branches we assembled in soggy layers that damp spring day I still remember for what the cat did when neither one of us was looking. We didn’t notice at the time, but the new structure we came up with last winter looks a lot like a bisected cerebral hemisphere: four lobes and four functions, essential for yearly plant rotation, quarters so efficiently balanced we couldn’t resist naming them North, South, East, and West.

We seem to be building a zone-five microplanet complete with “rhubarb islands,” “radish circles,” and (at the borders) aromatic “mint hubs” and “marigold stations” placed strategically to keep those marauding deer and gophers at bay. We wish they would nibble elsewhere, but really, where on earth would they go? A million acres of industrial corn and soybean surround us. Massive combines hogging both lanes on the highway remind us. Every June, without fail, the yellow crop duster swoops in, banks over the house a half dozen times to fully saturate the two big bottom fields. The pilot flies so low I swear I can see the bright white of his laser-focused left eyeball. I wave sometimes to show I’m friendly but he’s too busy tapping gauges to notice that guy down below licking a finger to see which way the toxic wind is blowing. Down here we’re okay, is the point, but out there beyond our nitrifying and daily watering is another story altogether. Parietal processes taste and touch; occipital vision; frontal cognition; temporal memories. Add sunlight to the mix and watch it grow: a mind, a field in which every kind of seed can be sown. Or a field, a mind in which fresh ideas start to form. We like hollyhocks in the background, native bee balm scattered with abandon on fish-bone swales. But that’s next year’s plan, the loam of future thought, word, and deed. Right now, I reach for the shovel, feel the kiss of another blister. Safe to say this body in motion needs a new pair of non-leather gloves.

in the description.

“perhaps the forerunner of what the state should do” (Tisler).

These folks mean well, I think, when they bring up my dead relatives. As conservationists they’re in the “forever business,” always focused on the future, but that doesn’t mean we can’t pause for a moment to reflect on the past, especially if it serves up a good story, a usable myth to help garner loyalties, stoke sentiment, maybe spark a little interest in the donor class.

Like the weather my mood today is cloudy and contradictory. On the one hand, I’m all in for this two-hour group hike through upland forest and small hill prairie. I grew up here so I’m familiar in general, but fine detail blooms on the north-facing slope. If we walk generally in a northeasterly direction, taking a hard left at the fence post where as a kid I always veered right, we may catch a glimpse of what survives: wild sarsaparilla, rattlesnake plantain, harebell, smooth shadbush, shooting star, hop hornbeam, tall forked chickweed, and so much more. I’m lifting these plant names from a list appended to the ecological description I found in the family archive. J, Director of Watershed Programs and our guide for the day, says that list, compiled over forty years ago, was just the beginning.

On the other hand, I can’t get my head around words like “relict” and “restoration” and “natural conditions.” Even “the beginning” is a tricky proposition when hearts and minds are dead set on forever. J knows all about my great-grandfather, who bought this place (story goes) with the intent to restore it. I’ve shared the C.C. Tisler article with her and D, Director of Land Preservation, but D and J don’t need me or an old family keepsake to remind them that intentions are one thing, actions another. Great-grandpa JP may have wanted, back in 1938, to give the land “a long rest from cultivation,” letting it “group” (Tisler’s words) “under the conditions of a century ago.” But his plan took shape in the abstract only as the land worked tirelessly through four generations, including my own.

“This used to be good woodland,” J says against a backdrop of towering white pine, hickory, sugar maple, and American elm. I’ve learned not to take what J says personally because “good” here isn’t about the woodland itself but an over-crowded canopy choking off growth down below. To restore light and life to the understory requires thinning branches, taking out a few trees, controlled burns, periodic reseeding. My great-grandfather had a notion, a rough idea, but these folks have a full-blown Management Plan with a clear objective: “to assure that the Protected Property will be retained forever in its natural scenic and open space condition.” The goal, in short, is “pre-settlement” goodness in a post-goodness world.

Across the river is what we’re up against—a once plush woodland razed to make room for more farmland. Uprooted tree trunks and severed branches smolder on the muddy riverbank. At first I don’t get it, then B, my neighbor to the west, explains: “There’s nothing that guy won’t clear. Nothing sacred.” The man’s intentions, in other words, are strictly utilitarian, profit-driven, and firmly rooted in a settler-expansionist mindset whose only limit is the reach of his legal holding. “That’s why special acres like yours are so important moving forward,” D says as we turn to retrace our steps back up the hill. As director of preservation, he’s making a case he doesn’t really have to make. Not today, anyway, with the smell of scorched timber so close and cloying in the moist afternoon air.

Without trying, D and B are helping me understand the truth about forever—that it works both ways and travels the earth in every direction, thwarting all human attempts to move forward by going backwards. Even the Plan acknowledges that conditions will change over time, that management activities will need to reflect those changes. It’s one of my jobs, for example, to keep an eye on insurgent “undesirables” (buckthorn, honeysuckle, phragmites), taking steps to remove, mitigate, and control “on at least an annual basis.” I’m all in for the shared workload and fully embrace a future-forward ethos, but the undesirables are adding up and the years keep getting ahead of me. When will it end, I wonder, or is this just another vaunted beginning? The goal is “pre-settlement,” but which settlement (French? British? U.S.?) and how pre? The State of Illinois sets the terms for dedication—no development, restricted use in perpetuity—but how does legal dedication, even with the best intentions, erase two centuries of planned devastation? It’s hard to get my head around this forever business when what the state “should do”—now, in the future, or in 1938—exists as a brutal consequence of what the state has already done.

“Watch your step,” J reminds us as we scale the last slippery slope. She’s concerned for our safety but we should also walk mindfully, paying attention to where we tread. One ironic consequence of benevolent exploration is the damage left behind by a steel-toed hiking boot. Following this narrow deer path is both impractical and, given pitch and angle, nearly impossible. So I tread where I tread, off trail and on high alert, noting in my head that this group excursion is just another form of human incursion. To make amends I join others in plucking garlic mustard, one of the most undesirable undesirables of all. This plant will grow anywhere, in full sun or dense shade. Its roots ooze a toxic chemical that prevents other plants from growing. “Actually changes the soil composition,” J adds, waving her hand over its delicate white blossoms. Then she yanks it, roots and all, from the soft, sandy ground.

Perhaps I wouldn’t (or shouldn’t) go so far as to say that white people are garlic mustard, intention the ooze, but the thought does cross my mind as we break right at the fence post and head for home. Everyone’s walking more briskly now as an ambivalent rain threatens with greater certainty. We’ll do this again someday but no one knows when. For now, abundant gratitude propels us forward on a grassy plane leveled long ago by melting glaciers.

“To the greatest extent feasible,” J says, quoting the Plan verbatim when I approach with one final question.

But that’s not what I’m asking. I’m not talking about preservation. I could rephrase, try again, but something tells me now is not the best time to bring up that kind of species survival.

in process.

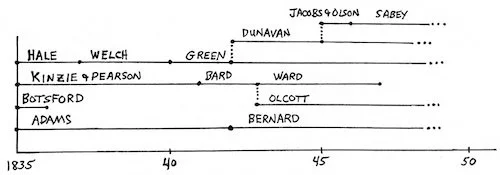

Even the names give off an aura of durability. Like coordinates on a map they mark moments in time, but time understood as divisible segments, much like land parceled out to be bought and sold over time. Each entry tells a story whose plot always turns on money. On June 15, 1835, John H. Kinzie and Hiram Pearson buy seventy-two acres (at $2 per) from E. D. Taylor, receiver. Six years later, on July 16, 1841, Kinzie and Pearson sell to William Bard ($550) who in turn sells to John Ward and Thomas W. Olcott ($ unknown) on the first of August, 1843. The process goes on for thirty-odd pages until, several decades later, time grinds to a halt in the lull between title transactions.

Dull in the abstract, the story comes to life when I sketch a rough chronology in my writing notebook:

I give up after fifteen years because the jumble of names and dates proves too unwieldy. In this stream of overlapping entries, I can’t always tell who owns what, who holds title and who doesn’t, who’s moving in and who out. What impresses me most, in the end, is the vigorous pace of turnover as one ownership claim yields to the next.

The timeline itself presents a problem, specifically my decision to plot transactions using points on a grid. I’m trying hard to understand land as process, but I keep defaulting to land as thing in a world made up of things. “It’s in our language,” Richard Epstein writes in “The World as Process,” and “nothing is more fundamental in our experience than this perception.” This land is mine; I own it, which is to say that I myself am a thing and this land is a thing, and to own it is to bear a special relation to it. In the language of the world as process, however, ownership in this narrow sense is inexpressible. Instead we “think principally of the impermanence,” of “being with the land,” of interacting, intermingling, flowing with the process, “perhaps controlling its flow but as much controlled by its flow.”

It’s not easy to see the world as process—to look at a rock, for example, and see the “flux of all” in its contained singularity. According to Epstein, those of us steeped in Western culture are so habituated to the grammar of things that we find it “extraordinarily hard” to imagine an alternative. I study aerial photos from my grandfather’s day and see signs of change. What once was a wildflower meadow is now an overgrown woodland. That cornfield across the river used to be a long stand of hardwood trees. Taken together the images suggest a world very much in flux, but all I can think about are things back then (woods, meadows) in relation to things as they are now. “Talking of change,” Epstein writes, “we find ourselves talking about things beyond any particular time.” This talk reveals a fundamental worry about the world “out there”—as it was, as it is, as it could be in the future.

Such worries were inexpressible, maybe impossible, in the time before land was thing. Now they show up everywhere—including in my diagram with its straight lines and imposing right angle. Anchored in the abstract, the story I’m telling erects a wall of fictional origin, as if Kinzie and Pearson (et al.) were the first to interact with this land. But what about the flow of people and process before 1835? By then almost all of Illinois had been surveyed, completing a project that started with the U.S. Land Ordinance of 1785. The plat map for the township I live in was certified in 1822, securing for private sale lands appropriated in the cessions of 1804 and 1816. In 1830, Andrew Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act, reaffirming the U.S. government’s unflagging commitment to settler terrorism as a cornerstone of domestic policy. Two years later, in the summer of 1832, Congress passed “An Act to Grant Pre-Emption Rights to Settlers on the Public Lands,” followed a month later by “An Act to Enable the President to Extinguish Indian Land Title within the State of Indiana, Illinois, and Territory of Michigan.”

Meanwhile 1835 proved a landmark year in the execution of public surveys when William A. Burt invented his “True Meridian Finding” instrument, later renamed Burt’s Solar Compass. Burt’s prize-winning device dramatically improved rectangular surveying and was instrumental in mapping, monetizing, and resettling the western United States well into the 1850s. As John Bowes remarks in “Indian Removal beyond the Removal Act,” removal in the Great Lakes region “was a business as much as it was a policy,” cutting a well-marked path for people like Kinzie and Pearson to “make money off the process.”

But that was then and this is now. And now is a pivotal moment for those of us born and raised in the land of the process. My family holds title to a little over one hundred acres of colonial flow, a stretch of impermanence we won’t own forever because “it” doesn’t last forever. I live here and will probably die here and find it extraordinarily hard to imagine an alternative. I couldn’t exit the situation even if I wanted to since living at all is living “off” the process in a country founded at the intersection of genocide and saleable rectangles. Every road and road sign is a reminder, as is my address when I enter it on the Native Land website to confirm that I live on or near the original homelands and traditional territories of Kiikaapoi, Peoria, Kaskaskia, Meskwaki, Bodéwadmiakiwen, Myaamia, Očhéthi Ŝakówiŋ, and their descendants.

It worries me to think that this acknowledgment doesn’t change a thing. It may speak to things “beyond a particular time,” but it doesn’t do much about time itself, the long accrual of names, dates, money, and resources adding up to the lucrative fiction of permanent holding. It’s in the language, the language in us. Nothing is more fundamental than this perennial mis/perception.

unsettling on the inside.

You came here as a Young American trembling on the inside as you tumbled into a world rife with beginnings, projects, designs, expectations. You came tumbling and soon you were scrambling through fields, over hills, in shallow waterways, not alone in your semi-private “country of the Future” (for others had tumbled with you) but presumed whole, self-contained, and possessed of an internal, untutored worldview manifesting on the outside as discrete, unassailable “you.” The rush of human experience came to you, as it comes to all, as neural potential become actual in a conditioned universe expanding outward but always dissolving/reforming like eddies in a stream in an endlessly fluid field of possibility. As a young and mostly carefree Young American you didn’t think much about neural potential or fields of possibility. Nor did you know—although you must have sensed, on the inside—that what made you both Young and American was the living residue of an “expansive and humane” Young American Genius or Destiny concocted long before you were born as a fictional counterpoint to the insidious inhumanity of Young American imperial conquest. Years would pass before you as an older Young American would sit down one summer to grapple with the local implications of this inhumanity, and just as a few seconds separate the first word of this sentence from its last, so too do decades of retribution energy fill the gap between a younger you’s experiential tumbling and the older’s experience of scrambling, right now in this moment, to find humane possibility in the trembling felt at the emergent and always dissolving edge of now. Here just prior to the present moment, reflecting on the past—or rather just prior to reflection (destabilized, dysregulated)—you cannot begin to understand this place, this land of fields and hills and waterways, without unsettling this place that is America in you. Generational throughput and the myth of American Genius stops right here, in the healing rush that comes just prior to completing this sentence. But as an older Young American you can’t begin to heal what’s insidious inside you without the help of sentences humming in the background like a nervous system ready at a moment’s notice to respond to what happens next. What happens next. Things arise and pass away but the stream endures. The stream is ground and refuge, noisy with neural activity and teaming with potential. Here in the substrate (below ground, in refuge) you want to believe anything’s possible—new designs, new projects, new beginnings, new Americas. How very American of you. But as an eddy of potential coalesces then dissolves, so too does this experience of being so very American rise out of and fall back into an ever-evolving field of unstable energy. This is how life begins and ends for you, but it has nothing to do with Destiny. Beginning again, at the edge of now, you may feel a particular feeling like falling. But just when you think you’ve found that edge, there is no you, no now, no feeling.

Works Integrated

Biles, Roger. Illinois: A History of the Land and Its Peoples. DeKalb: NIU Press, 2005.

Bowes, John P. “Indian Removal beyond the Removal Act.” Native American and Indigenous Studies, 1.1 (Spring 2014): 65-87.

Emerson, Ralph Waldo. “The Young American.” Essays & Lectures. New York: Library of America, 1983.

Epstein, Richard L. “The World as Process.” ETC: A Review of General Semantics, July 2016: 213-232.

Indian Land Cessions in the United States, 1784-1894. American Memory Collection, Library of Congress (www.memory.loc.gov).

Muller, Richard A. Now: The Physics of Time. New York: W.W. Norton, 2016.

Native Land Digital (www.Native-Land.ca).

Natural Land Institute, An Ecological Description of Marsh Relicts, LaSalle County, Illinois, September, 1980 (author’s copy).

Tisler, C. C. “Ramblin’ Around.” Daily Republican-Times, July 1, 1938 (p.4).

Ward, Larry. America’s Racial Karma. Berkeley: Parallax Press, 2020.

White, C. Albert. A History of the Rectangular Survey System. PDF version (web). Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management, 1983.

Bill Marsh is a writer, teacher, and non-Native land custodian living on Kiikaapoi and Potawatomi land. His writing has appeared in Allium, Bayou Magazine, Briar Cliff Review, Cimarron Review, Copper Nickel, Timber, Ruminate, and Writing on the Edge, among other journals. His work has received multiple Pushcart Prize nominations and two of his essays are cited as Notables in Best American Essays 2021 and 2022.