Alexandra Chang’s latest short story collection, Tomb Sweeping, dives into many lives undergoing a transition or change, for the better or for worse, all acted upon by the same humane desire: ambition. From a rupturing immigrant family haunted by flies, to a sister rivalry inundated with love and hatred, to the question of whether complicity and guilt are, or should be, passed down through generations and bloodlines—each riveting story places ambiguous morality and the fragility of dreams at the forefront.

In this interview, Alexandra and I enter a conversation about trust, disorientation, and disillusionment. What happens when our ambitions work against us, and how do we navigate a world with so many systemic forces opposing us?

Phoua Lee: A lot of the main characters in your stories aim to lead a life of purpose. I’m curious about the definition of a “purposeful life” in both American and Chinese cultures. How does that definition inform your stories?

Alexandra Chang: What you’re noticing with these characters in my stories and this shared quality among them is totally right. A lot of them are seeking a sense of purpose or a sense of meaning. Some of them are very ambitious and unabashedly ambitious. Some of them are disillusioned after having a sense of purpose and realizing that their purpose put them on a harmful path or a path that led them to some sort of loss.

In American culture, we have the idea of the American Dream. We live in a very late-stage capitalist society where purpose often equates to financial success in some form, and usually, that is translated through having a good career. There are characters in my book who are striving for not only financial stability but also wealth. For example, in “Cure for Life,” we have a character who comes from a lower-class background who is dreaming of the American Dream, of class mobility, of getting himself out of his “lot in life.” He isn’t necessarily able to do that. A lot of the characters are coming up against these walls where what they’re hoping for is out of reach because of who they are, because of where they are in life, and because of systemic forces.

Then we have the purpose that you’re hinting at as well. What does it mean to have purpose in life from a Chinese background or Eastern cultural background? There are characters in my work who are trying to find meaning in their relationships with their parents, especially aging parents, and that sometimes contradicts the same drive they’re going for in American culture. With “Persona Development,” Patricia has achieved what she should be achieving by the time she’s in her early thirties. She has moved up in her career. She’s financially successful. She’s doing well in her job, and when she becomes pregnant, all of that doesn’t satisfy her anymore. She feels this thing that’s missing, and she’s trying to figure out what kind of life she can lead that would make her feel at ease or like there’s alignment between what is purposeful for her and what is purposeful in the grander scheme of life, and that’s outside of the American Dream.

It turns back to family. My characters often turn towards family if they are Chinese, Chinese American, Asian American. They turn toward family, turn towards history, and find purpose or meaning through those relationships. Some characters hold both worlds. In “To Get Rich is Glorious,” there is a character who goes against what is expected of her in the filial sense and wants something more from her individual life. You have characters who have a wide range of definitions for purpose.

Lee: What you said about purpose and success reminds me of a certain trend I’ve been seeing lately. When it comes to purpose, the American definition is different from the Chinese definition, but at the same time, there are intersections. The Chinese “let it rot” movement is a protest against hard expectations and lack of economic opportunities for Chinese youths, wherein the youths embrace a deteriorating situation and “give up.” This movement has transferred over to America as the “bed rotting” trend, and now some American youths are posting social media content about being in bed all day as a form of self-care. So these two cultures are bouncing off of each other.

Chang: There is so much pressure on kids and young adults to do the best in their class, go to the best schools, then get the best jobs, and then you’re “fed” for much of your life, like if you work really hard and you get all of these things, your life will get better or your life will be easier. Somewhere along the way, a lot of people—like these very smart kids—are realizing, “No, that’s not true. You’ve been feeding me lies. My life is not going to be easier. It’s not going to be better.” So there is that question of what’s the point of putting all this effort, time, and energy toward something that will never fulfill me.

I think a lot of millennials—people in my generation—have had to deal with disillusionment surrounding work and productivity. We should all embrace bed rotting a little bit more. It’s a response to all of these pressures that are not healthy for humans and for existing.

Lee: Your story “Li Fan” blows my mind. It makes sense when read conventionally, start to finish, but it also tells the same story with different nuances if read backward. It’s startling because this piece starts with death, and when we think about someone who has passed away, we first start with their death, then move on to their life and accomplishments throughout the time we’ve known them, a sort of memory commemoration that mirrors the structure of this story. How did the concept of death influence your decision to structure this piece as reverse chronological?

Chang: When I think about structure and story, especially regarding the content of a story, it has to match. It has to feel like the two are working in tandem to enhance the form overall. I’m not the first to write a story that moves chronologically backward in time, but I have read several and it had been in the back of my head: I want to write a backward story one day.

I had this character in my head of the Asian recycling woman. This is a character I had an interest in for personal reasons. My own dad at one point went around the neighborhood and collected people’s recycling out of their bins. I’ve seen plenty of Asian recycling women in all of the cities I’ve lived in. This type of person can often be invisible, dismissed, or treated with disdain. I’ve seen people come out and be like, “Hey, don’t take that out of my recycling.” Why? What is the impulse to treat a person in that way? The question of “Who is this character? Who is this person?”—those are motivating questions for me any time I write a story.

In terms of the backward story and this character, it occurred to me that the two could be joined into something productive. How did I start with death? I’m not sure. It just felt natural. It felt like the right move. This is something that I’ve done before. “Tomb Sweeping” also starts with the ending. It starts with death. It is this impulse to start at the end and try to explain that end. I’m a writer who does not like to hold their cards close to the chest. I want to lay it all out there so that the mystery is not about what’s happening, what’s going to happen, or what the character is keeping a secret. I want the mystery to be about the emotional stakes, the unanswerable questions like, “How do we live in this world under these conditions? How can we survive when there are all of these forces opposing our survival?” In “Li Fan,” it’s like, “What is value in life?” It’s more of an emotional mystery that I’m concerned with, so it made sense to start at the end and move back in time.

Lee: Right? As readers, we’re always so embroiled in getting to the end, getting to that big twist, but at the same time, what if that big twist is at the beginning, and it’s up to us to unravel it and figure it out?

Chang: Sometimes, the greatest pleasure of reading a short story is the disorientation at the beginning. You go into a story with a general sense of trust in the writer, and that trust is given a certain length or extent. Having a story with a lot of disorientation in the beginning goes against what the reader is expecting and anything that we are naturally comfortable with. My hope is that once the reader figures out what is going on, there’s a huge payoff.

Lee: Now that you’re talking about disorientation and the trust that the reader has in the writer, it brings me back to many of the main characters in your short stories. I realize just now that I don’t trust any of them. That’s what makes it so honest and sincere. Usually, authors are like “How can I endear this character to you? How can I make you like them?” Your characters are so real and multifaceted that while I was reading I was like, “How do I know if you’re telling the truth?” They all felt like unreliable narrators to me.

Chang: I’m not interested in likability with characters. I am drawn to characters who are complex, contradictory, and very particular in the ways that they might exist in the world, and that they are capable of holding contradictory views. That is how I see people. I don’t believe in the pure objectivity of a person’s view. What I’m concerned about is that a reader believes that this character exists.

My characters have desires, and they might come from good places, yet they still mess up, or they have these selfish impulses that lead them to make strange decisions. Or they lash out. They are driven by anger or guilt. With any first-person narration, it is my belief that there is no reliable first-person narrator. No person can be fully reliable in terms of telling the truth.

Lee: I guess I’m the “naive reader” because, most of the time, I automatically side with the narrator. I’m like, “I’m on your side, and I believe everything you’re saying.” It refers to what you were saying earlier about the trust that the reader has for the writer, which naturally transfers to the narrator.

Chang: You’re trusting that the writer is not going to trick you. You want to build trust as a writer, but that’s different from the character. The character is their own person. We have a natural inclination to side with the first-person narrator, but sometimes that’s where you can see a writer surprisingly and satisfactorily play with that trust. That builds trust with the writer even though it doesn’t with the narrator.

Lee: The trust for the narrator being different from the trust for the author—these are concepts I’ve never considered before. I’m glad to be able to talk to you about this.

In a past interview, you said that you had written up to four endings for FuFu in “To Get Rich is Glorious.” I’m curious what one of these alternative endings might be! How did you arrive at your current ending, and what do you think makes it work?

Chang: Great question! My first draft had an ending where FuFu was in prison, and the last vignette was of her lying in her cot and staring vacantly up at the ceiling. I sent that story into workshop, and nobody really commented on the ending that much at the time. I got one note saying, “Maybe you could try a different ending.”

I sent it to George Saunders, who is one of my professors, and he is a very, very careful and nit-picky reader. He pointed out that the ending wasn’t in line with the way that the character had behaved throughout the story. What you choose to put into a story really, really matters. He said, “Yes, FuFu, this character, I completely believe that at one point in prison, she does lie there and stare vacantly often to the distance or ceiling. That is believable. But the way that she behaves in this story and the momentum of this story doesn’t fit in terms of how this story would end for her.” He pointed out that she was very defiant from the beginning. She’s always constantly trying to assert herself in the world. Wouldn’t she continue to try to do something under her circumstances?

That’s when I tried a couple of different things and did some more research. I wanted a return to her family member. I found this thing when I was researching that just fit. It made perfect sense. In these Chinese prisons, there was one prison that had a mother-daughter day where all the mothers visited their daughters in prison and looked at all the things they had accomplished. They had sewn some stuff, they had cooked, they put on a play and the play was about being a good mother or being a good daughter. It’s a return to duty to your family. I thought, “What would FuFu do?” She would obviously be the star of this play, and everyone would think she’s doing so well because she’s done so well throughout her life. Only her mother is able to see that this is a facade, and she hasn’t actually changed. Her ambition is still there.

Lee: I’m getting a lot of that too, from the last line in the story about the tilt of her mouth with the pride that remains undiminished.

Onto what you said about endings and our expectations for endings—we usually talk about endings in terms of the story structure, like is this how the story is expected to end, or is this how the reader would expect the story to end? I’ve never considered it in terms of characters. Saying that your ending was based on how you structured FuFu—that totally makes sense now.

Chang: I understand the struggle. I think endings are very hard.

Lee: Because you want them to be expected, right? Like, the reader knows they’re going to get there eventually. But you don’t want them to be too predictable, and that’s where the difficulty lies.

Lee: There is a quote from “To Get Rich is Glorious” that says, “It seems, in this case, he who grows up without want has the luxury of satisfaction. She who grows up wanting is never satiated.” To add to that, why are your main characters with underprivileged backgrounds so compelled by ambition? How does attaining a better life tie in with class, status, and reality?

Chang: That is a question I’ll probably continue to ask in my work. This comes from growing up in a certain class and having a desire for class mobility, to have a life that’s not determined by scarcity and trying to make it to the next day. A lot of my characters live in this future they desire where they don’t have to worry as much and there’s less stress. That helps them continue to live—the hope that this future exists somewhere. That hope and that desire can also be dangerous because it makes them turn away from what might be causing some of these problems. We can experience class on an individual level.

In “Flies,” the characters are living in a pretty crappy house that they’re renting, and this is causing a lot of stress on this individual family, and this child who is realizing that her family is not financially stable. There are ruptures because of this.

We can experience class dynamics on a broader level, like in “To Get Rich is Glorious.” Some things are out of one’s reach because of systemic problems and societal forces that are beyond an individual’s control. Sometimes, that can be very confusing for people. A lot of these characters want a better life because they are from marginalized, lower socioeconomic backgrounds, and they are turning towards this hope because they’re told this will make their life better. The reality is that this is not within reach for many of them. This disconnect is what causes a lot of drama in their lives.

“She Will Be a Swimmer” is another story that starts with a foreboding. There’s no safety net there. What the main character is trying to build for himself in this country as an immigrant is like trying to build a house on little toothpicks. It’s going to fall apart, and nobody will be there to catch him. That is the reality for many people in this country, immigrant or not.

Lee: That ties in with my next question, dealing with parent-child relationships in an immigrant dynamic.

In “Farewell, Hank,” Adrienne refers to herself as controlling, which is nonconforming because it is usually the parent figure who holds these attributes. But in an immigrant family dynamic, sometimes there will be a “controlling daughter” figure and this is because she is more assimilated to the American culture and because of that knowledge, takes it upon herself to be a sort of guide and advisor to her parents. We see this role again in your story, “Persona Development,” where the main character Patricia has a fixation on monitoring her elderly parents. What led you to incorporate this relationship dynamic in your story and how did you capture such intricate details?

Chang: I am the oldest daughter of immigrants, so I would say that I’m the controlling one in our family. Shout out to all the oldest daughters of immigrants! This is a parent-child dynamic that, like you’re saying, is very particular to a kind of identity. It’s a whole way of being, then there’s the sliver in there of being the oldest daughter—the daughter who somehow takes the lead in the family because they are this guide, this translator, and because the parents end up needing to rely on someone who can be the conduit between two worlds.

Both Adrienne and Patricia have similar traits in the sense that they are over-controlling types, not only in the sense of controlling other people but also controlling themselves or certain parts of their own feelings or lives. That gives them a sense of—not even peace—but a sense that they can control parts of their life that appear chaotic to them. The chaos typically comes from parents, especially aging parents.

What was really important in depicting this kind of parent-child relationship was that it not be flat or become a trope or a stereotype that readers might be overly familiar with or be able to put into a box. That’s where those particularities that you’re mentioning come in. The quirks and strangenesses that exist in these characters and these relationships, something as minute as Patricia watching her mom sing and being like, “Wow,” and she continues to watch it. That shows multiple levels of relationship: the control, the desire for closeness that a lot of children of aging parents feel, and also just love too—a very complicated kind of love. It’s through those details that a relationship becomes particular. That emotional feeling can somehow rise into the universal. It is through particularities that a story can become universal.

Lee: There’s a misconception about how the more broad and general you are, the more readers would be able to relate. Usually, they say that if you get too specific, that’s when readers are like, “Oh, no, I’ve never experienced that before in my life.”

Chang: In terms of the human emotional range, we have shared emotions. We’ve all felt angry, frustrated, desirous, hopeful. Many of us, hopefully, have felt loved and loving towards others. To elicit those emotions in fiction, it is through being particular. If you say, “Johnny loved Mary,” that doesn’t make me feel anything. If I were very specific, like “Johnny did this and that, and Mary left town, and he didn’t see her for three years,” it is through story that we’re able to conjure those emotions on the page.

Lee: What comes across strongly in “Cat Personalities” is the estrangement between two friends. There is growing tension between the two as they start insulting each other using their cats, to the point where there is an undertone of comedy and absurdity. How much fun, if any, did you have portraying these bitter truths of friendship?

Chang: I definitely had fun. When I’m writing, I need to be able to have fun in order to continue, even if it’s about something that is painful or that hurts or that is a little bit dark. A friend breakup can be dark, but it’s more painful because we don’t have very good scripts for what to do when we’re drifting away from a friend, or when we don’t want to be friends with someone anymore, or feel like we can’t be friends with someone, whereas we do have very clear scripts for breaking up with a romantic partner. Friend breakups can range from something absurd to fizzling out and ghosting each other. There’s no closure.

In this particular story, I wanted to lean into the absurdity and this feeling that you can’t talk about how you’re not compatible anymore as friends. They have to talk about it through their cats because they don’t have the language to talk about it directly. It’s a funny concept to me. It was inspired by a real-life moment when someone said something about my cat that felt like they were saying something about me. So that’s where I ran with it.

Lee: That’s funny. My thought the entire time reading this story was that this is what happens when two non-confrontational people argue.

Chang: Yeah, definitely playing with the “catfight” idea a little bit too.

Lee: Our closing question: What are you setting your literary sights on, to be explored in your future works and projects?

Chang: I’ve talked publicly about one project that is an expansion on “Cure for Life.” It takes place in the world of the grocery store in “Cure for Life” and has a lot of similar questions about class, ideas of success, and labor. It follows a bunch of people who work at the grocery store together—a very high-end, bougie store where they’re servicing people in this town who are of a much higher class than they are, and this dynamic between the workers and their customers and the dynamics between the workers themselves. That’s one thing I’m working on.

I’m also in the early stages of starting another project that asks the same questions I’ve asked in my first two books about the self. Who are we in relation to others and in relation to the larger world, and how do we form a sense of self in relation to everything around us? I’m expanding that a little further to be about the nonhuman world, not only human society, but about the planet, animals, and what is beyond just human understanding.

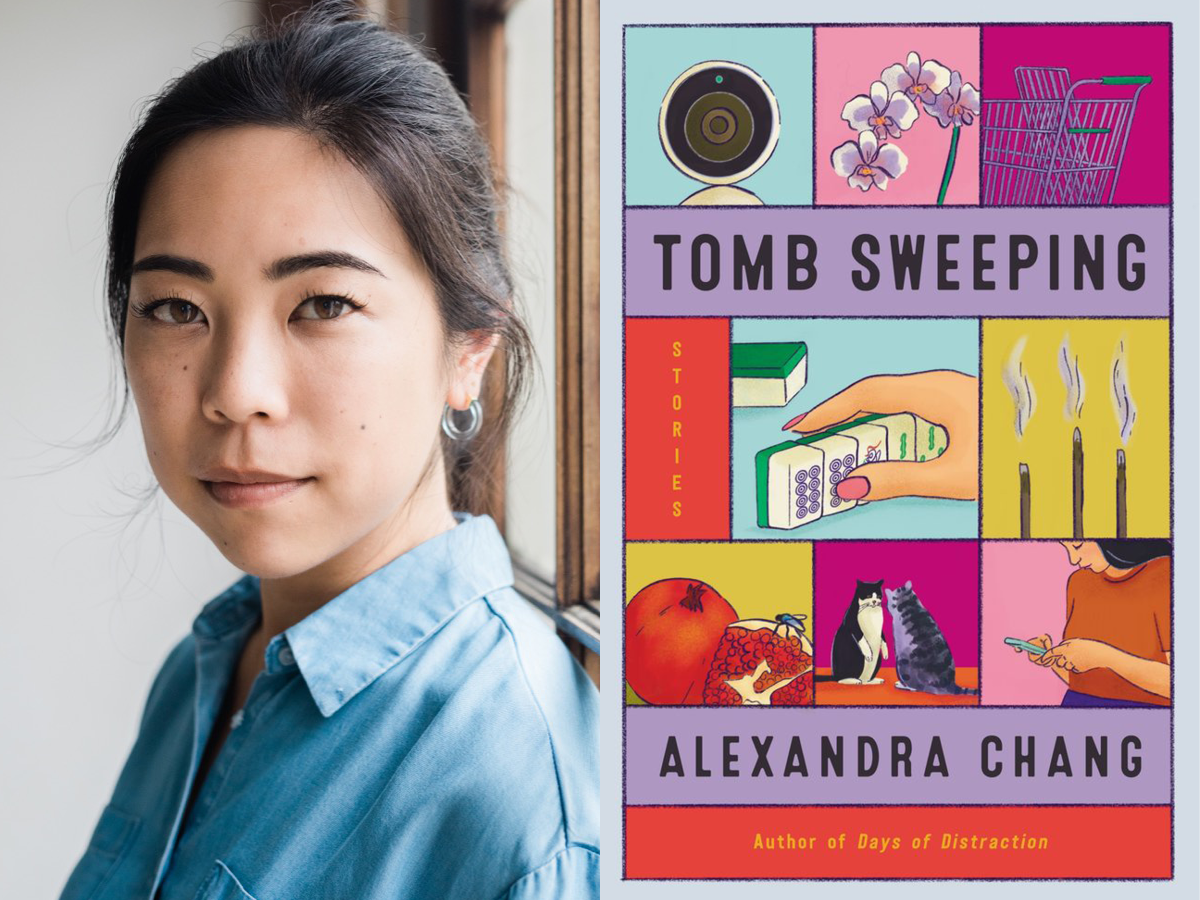

Alexandra Chang is the author of Days of Distraction and Tomb Sweeping. She is a National Book Foundation 5 Under 35 honoree, and she currently lives in Ventura County, California.

Phoua Lee is a Hmong American writer from California. She is an MFA Creative Writing student at California State University, Fresno.

Photo credit: Author photo by Alana Davis