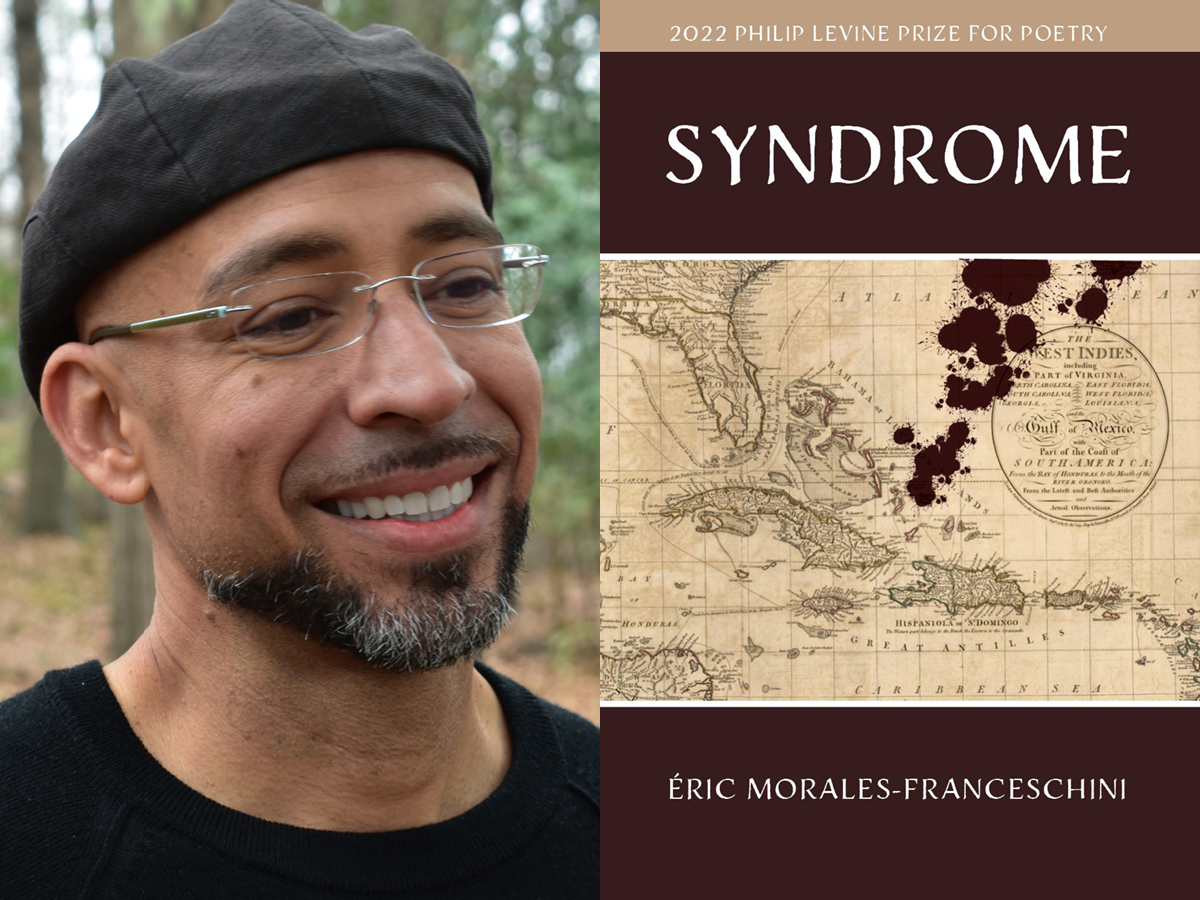

Editor’s note: In this conversation, writer Victoria Monsivaiz talks with author Éric Morales-Franceschini, winner of the 2022 Philip Levine Prize for Poetry for the collection “Syndrome,” selected by Juan Felipe Herrera.

Victoria Monsivaiz: Your poem “A hystory, otherwise known as Imposter Syndrome” suggests a sense of navigation with culture and identity, and hurdles with societal expectations seemingly both outside and inside the Puerto Rican community that you write about. For me, this brings to mind the expression “Ni de aquí, ni de allá,” which I’ve heard from some Latinx/e writers and artists who’ve experienced a similar sense of navigation.

However, I’ve also heard some Latinx/e writers and artists who are attempting to veer away from this expression, because they feel that it establishes an implied sense of “less than” or a mode of othering. What’s your perspective on the expression of “Ni de aquí, ni de allá”?

Éric Morales-Franceschini: I think it conveys a key aspect of our lived reality, namely as some enigmatic, untethered Other who doesn’t know where to call “home,” yearning to belong and feel whole but not fully welcome or comprehended here or there. That’s a stark way to put it, but it’s no easy thing to live with. Gloria Anzaldúa, of course, is the one who most convincingly rearticulated this in-betweenness as fecund, as that which enables us to think and become otherwise — a new hope arguably, or at least a singularity worthy of its own name (mestiza? Latinx?) and dignity.

But either way, we have to be wary of “ni-ni” rhetoric that doesn’t convey some of the asymmetries at stake: Some of us were born or even raised “south of the border,” while others have never stepped foot in their ancestral patrias; others can speak Spanish (or even Nahuatl, Quiche, or Quechua!) fluently, while others barely at all; some of us are legally aquí, others perpetually at risk of being deported; some of us are sympathetically welcomed as “exiles” from communist “regimes” (i.e. Cubans, Venezuelans), others stigmatized as ingrates, criminals, or worse. Insofar as “ni-ni” rhetoric doesn’t invite us to scrutinize these nuances, let alone the fact that aquí is an imperial power vis-à-vis allá, it shouldn’t be our only or most crucial category or phrase. There are others, after all: i.e. “We didn’t cross the border, the border crossed us.” Or, “We’re here because you were there!”

Monsivaiz: After rereading your book, it dawned on me how little I know about Puerto Rican history. I noticed that when I was compiling research, a lot of the material the internet would first introduce to me would primarily begin with the establishment of colonization, rather than history predating colonization in Puerto Rico.

For present and future readers who are being introduced to Puerto Rican history for the first time by reading Syndrome, what would you want them to take away from the history you’ve included in some of your poems?

Morales-Franceschini: I can never presume my audiences know much, if any, Puerto Rican history, even if those audiences are themselves Boricua! We just aren’t taught our (or each other’s) history, let alone our literature and philosophy, which is why there are so many endnotes that contextualize the poetry, in hopes to enrich and edify the reader.

On that note, the takeaways aren’t exceptional to Puerto Rico. This is a story as much about the multivariate, longstanding, and pressing injustices that so many of our kin in and from the Global South suffer as it is a story about the periodic convulsions and epic stands we have taken, or could and should take, to say loudly and unapologetically: This is not the best of all possible worlds.

Monsivaiz: Storytelling and consejos are known to be an important factor of passing down not only history (directly from points of view of underrepresented and marginalized communities that are rarely, if at all, told or seen in history books — or, books that individuals are being denied access to—such as banned books), but also ánimo, hope, strength, truth, caution, etc. What has partaking in storytelling and consejos done for you as a writer and individual, and what do you hope your readers take away from it?

Morales-Franceschini: At the risk of sounding cliché, it’s a way in which I can move others, as well as rethink ideas beyond the strictures of data, disciplinary norms, and academic jargon. With storytelling, I can more freely enlist affect, desire, intimacy, dialogue, and drama.

Stories also tend to be intelligible. A poetry that tells stories is likely, thereby, a poetry that is accessible, not gimmicky or solipsistic. I have some tolerance for purely aural, incantatory-like poetry or avant-garde experiments, but by and large I want to feel welcomed, edified, and moved by poetry, not utterly lost or simply amused.

Monsivaiz: You’ve also published numerous scholarly works that aid in exposing and dismantling colonialism, providing deeper insight into the ethos, logos, and pathos of militancy, etc. How have your scholarly works influenced your drive to create poetry? Or perhaps, why did you choose poetry as your artistic outlet to write Syndrome?

Morales-Franceschini: I suppose I’ve answered that somewhat, with my nod to the powers and indulgences of storytelling. But poetry isn’t reducible to narration, of course. And mine is no different. Syndrome has its share of etymological inquiry, incantatory prayer, rebellious hymnals, historical polemics, and speculative theory, all trying to make sense of a visceral, complex reality.

So it works vice versa: My poetry is indeed heavily indebted to my studies in history, psychoanalysis, political economy, and critical social theory; but I find that, at times, only via poetry can I adequately express the gravity and intricacy of not just a given fact, but what I should (like to) do in light of that fact. Poetry becomes thereby the occasion to reckon with reality, not just document or annotate it, and it does so by whatever creative means necessary, or at least more eclectically and imaginatively than academic norms allow. That, anyway, is why I’m drawn to it.

Monsivaiz: Has the completion of Syndrome sparked any inspiration to write another poetry book? If so, focusing on what? If not, what projects are you now eager to pursue?

Morales-Franceschini: For some time I’ve hoped to write on—and let reverberate, poetically—the summer of 2020, that summer when so many Christopher Columbus monuments were so spectacularly “decommissioned.” But for that to be a worthwhile project, I’ve had to commit to a fair amount of research, since it has led me to an inquiry on Columbus memorials and counter-memorials throughout the Americas from 1492 to today. It’s not exhaustive, needless to say, but the archive I’ve amassed is rich: papal decrees, travelogs, court cases, epic poems, paintings, sculptures, hymns, logos, etc. and their indigenous, Black, and populist rebuttals. So I suppose this next project is, thus, a sequel to Syndrome, whose last poem is “inspired” by the Columbus monument in Puerto Rico, the largest Columbus monument in the world!

Born in Puerto Rico and raised in Tampa, Florida, Éric Morales-Franceschini is a former construction worker, U.S. Army veteran, and community college graduate who now holds a Ph.D. from the University of California, Berkeley and is an Associate Professor of English and Latin American Studies at the University of Georgia. He is author of the chapbook Autopsy of a Fall (Newfound 2021), winner of the Gloria Anzaldúa Poetry Prize; and the scholarly study The Epic of Cuba Libre: The Mambí, Mythopoetics, and Liberation (University of Virginia Press, 2022), winner of the MLA’s Katherine Singer Kovacs Prize. Syndrome, selected by Juan Felipe Herrera for the 2022 Philip Levine Prize for Poetry, is his debut full-length poetry collection.

Victoria Monsivaiz is a second-generation Mexican American born in Denver, Colorado, and raised in California’s central San Joaquin Valley. She is currently pursuing her MFA in creative writing (poetry), with an emphasis in publishing and editing. She serves as president of the Chicanx Writers and Artists Association (CWAA) and works as a teaching associate at Fresno State. Her writing as of late focuses on her experiences growing up in a single-parent (and later on) multi-generational household, dissecting her current and former familial bonds.

Photo credit: Author photo by Rebecca Matthew