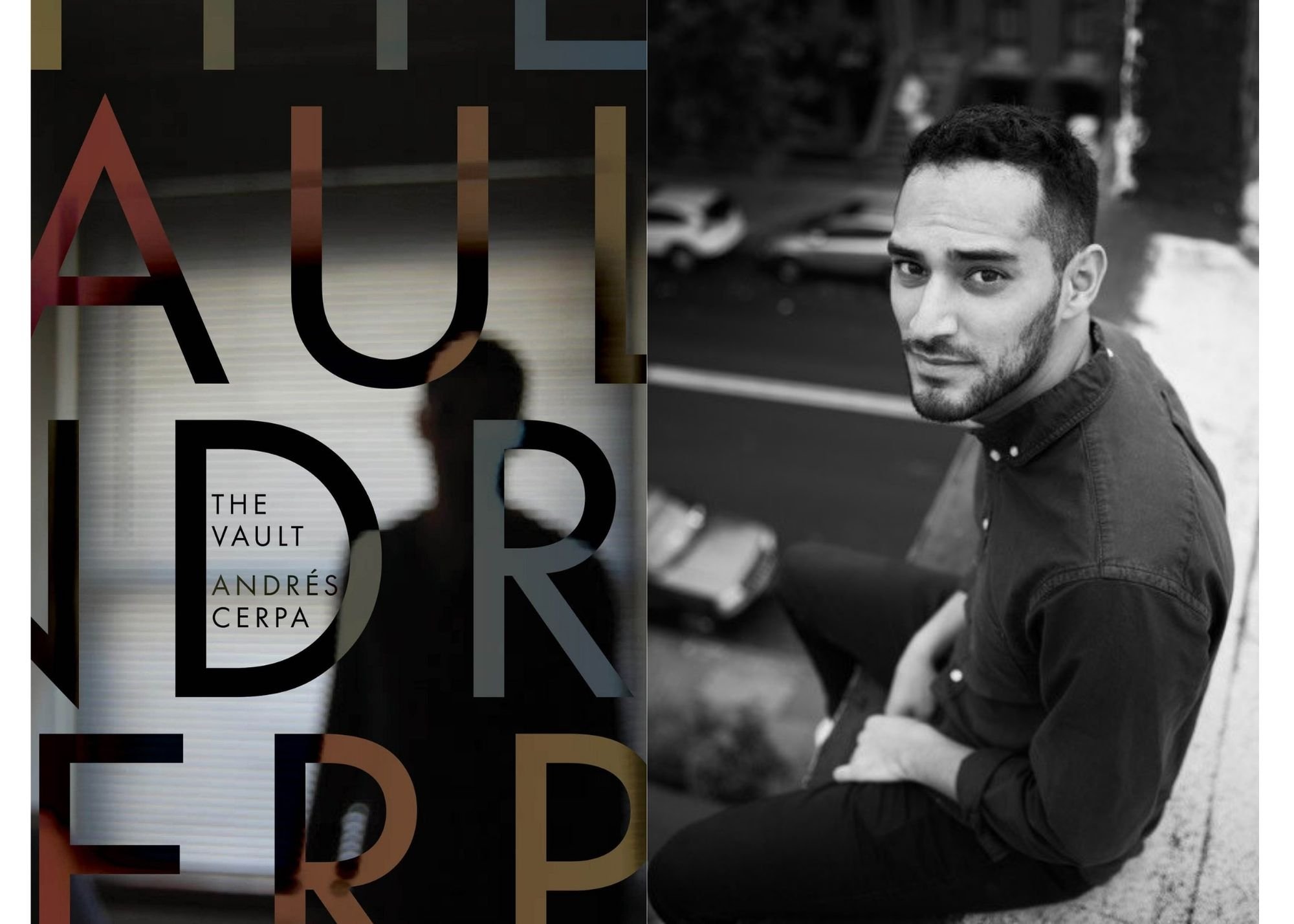

I met Andrés Cerpa on a video call; he Zoomed in from New York, while I was in Fresno, California. During our conversation, he read to me from his newest poetry collection, The Vault, written about the ocean of grief and remembering. We discussed his creative process while constructing his second book, the writers Larry Levis and Franz Wright, and his projects for the future. The Vault, published in June 2021 by Alice James Books, is currently longlisted for the National Book Award in Poetry.

Rebeca Abidial Flores: First of all, I just want to say congratulations on your book being longlisted for the National Book Award! This is exciting. What does this recognition mean for your poetry and for you as a writer?

Andrés Cerpa: I think for me as a writer, the award is interesting because the book is kind of like doing the work by itself. I’m releasing it into the world and it’s making its way to being noticed, and it’s being closely read by people that I admire. Maybe more people will read it because of this, which I think is awesome. That’s what it’s all about: It allows for more connection and for people to see the book.

Flores: [At this early stage of the interview, Andrés reads me the untitled poem on page 72 of his book straight from memory.]

Cerpa:

To remove my own heaven,

I walk. Snarl the field.

Hitch my boat & lie down.

It’s simple plan,

be simple. Make tea.

Wake up & breathe a bit before the future.

It’s a long walk home

Walking backwards.

I’ve yet to give my oar to the sea.

Flores: You read off the dome!

Cerpa: I read the poems to myself so often during their construction, and I’ve recorded myself reading them to kind of see how they flow and work, that they just kind of get in there. As I write new poems I feel like some older ones get pushed out, but The Vault is still pretty fresh in my mind.

Flores: Reading it out-loud becomes a part of the construction of a poem, or of a singular piece? And you create the whole book like that?

Cerpa: I’ll be reading individual pieces while recording myself. I read different drafts of them, trying to find out how to work on that page or that piece. And then in the construction of the book, I’ll record different orders over and over again to see the relationship between poems or between sections. I end up by the end of it having listened to myself reading the poems quite a bit.

Flores: The audio component is very much a present process of your work. How often do you feel yourself going back to those recordings?

Cerpa: Not necessarily every day. Recording happens a lot later in the process, like after I’ve had a lot of forms and refining. I think my process is that I write a ton. I write and write and write, and then exhaust whatever idea or momentum that I’ve been working with. Then I go into the recording stage. Returning to the poems is super important in terms of every draft then becomes recorded. Recording the entire book and then listening back to it is a little maddening. I’ll tell you, no one should listen to themselves talk that much. [Laughs.] But you know, it’s a tool that you’re using.

Flores: When we enter The Vault, it starts mid-sentence. And soon enough, word by word, line by line, page to page, we are led into the deep darkness of grief. We began fragmented and searching. What was it like designing this opening? Did you always know it would feel splintered?

Cerpa: Thank you for that reading of it. I constructed the poems like starts and stops. In a certain sense, I’m attempting to generate momentum even past the opening. I was really busy during the time of construction, and I think the form of my life sort of began to enter into the form of the poems. The process of writing, especially like a longer work, long sequence or a book, is that you’re revisiting poems or revisiting an idea and hoping that you can catch the momentum of what has happened before.

The lack of punctuation and starting mid-idea is the implied narrative that’s looming in the background but not necessarily coming to the forefront at all moments. This is a symptom of the starting and stopping that I’m doing. Constructing the book is a device for me as a writer to enter it more fully. I like to drop myself in. If I’m there mid-sentence, mid-story, if everything is kind of jumbled, then maybe I can catch the momentum that I had previously and continue on riffing. It becomes a tool too, and then it kind of bled its way into that first section.

Flores: In the beginning sections of the book, there’s an image of the ocean and water that creates this purposeful visual darkness in the book. What it was like to work with a visual image?

Cerpa: We didn’t have the image until much later. The guiding line is the verse that’s in there:

Let there be a vault to divide the waters of heaven

from the waters of the earth.

I think that gave me direction throughout the book. You’re writing it over years and there’s these two very distinct sections and that gave me something to look at. There’s a wall above and beneath and so in a certain sense each section is looking more closely at that divide. I always had the idea that there would be something in the middle but I didn't know what that was. It’s wonderful to work with Alice James Books because they move towards imagining.

Flores: How did the letters to Julia and Gregorio come? Did the letters come piece by piece, or did you write each letter to the person receiving them one by one?

Cerpa: When I think back, it came piece by piece, and in a certain way I think that happens because they’re sort of like letters that aren’t meant to be sent. They’re letters that can’t be said because they would disrupt something. So, there’s disruptions inside of the book, but I also feel like they’re disruptions inside of the speaker’s life, and there’s this question of whether to let in or let out. The first poem of my first book is a letter, so I think that I’ve come back to this idea of letters and questioning what I would like to share, what I would not like to share, and what my speakers are holding close to themselves.

Flores: Are you the kind of writer that needs to bank? Like, you need a lot of work in the bank before you can start roaming? Or do you move things around as they come?

Cerpa: I think I need a set. I need enough pages to make a whole book, and that comes pretty quickly for me. I’ll have my poems and I’ll try and order them, put them together, see what is resonating off one another. I’ll highlight lines from a poem that I don’t necessarily love, but I think that there’s a line there, and I’ll just arrange the poems as if they are a book. I put a clip on it, and then as I continue to write I’ll hold all my new poems next to the older ones, and then it’s almost like an annex. Then I take poems out and bring poems in. I think it’s really successful when I write a new poem and I think, oh okay, this is speaking to what these other maybe two or three poems are doing, and I can take those three out. I start with quite a bit of writing and then try to hone it down. It’s good to see what I’ve been thinking about, what images are circling, and by reading my own work I can see where I want to try and go next.

Sometimes I think that there are moments that are connected, and taking a step back together with the reader, pausing, making, or reminding them of an amalgamation of images or ideas and then propelling forward. I think there are moments of pause and I think I learned that from Larry Levis, especially in his long-form poem “The Perfection of Solitude,” where there are these moments where there are a bunch of images that have already been sort of brought up and cycled through in a quick, small snippet, and then it moves forward.

Flores: Larry Levis is from my hometown, Fresno! Poetry is a big part of our writing and communities here, so thank you for the Larry Levis love. I listened to your recording of your book’s title poem, “The Vault,” on Poets.org. At the end, you said: “I wrote this poem to love the world more.” Do you feel that way now?

Cerpa: I think so. Franz Wright was one of my favorite writers, and as wild and complicated as that human was, something about how his poems are sad but he was happiest when writing them. I think that I get to live out and explore a variety of different ways of being inside of the world inside of my poems. In those explorations, I hope that I find a better way to live or a perspective that I can stand behind. Not all of my poems or speakers do the right thing. They make mistakes, they’re horrible in moments, and they have lots of different regrets. But I think that being able to stop and see those things helps me be appreciative of what’s in front of me, of my actual waking, moving life outside of the desk and outside of these moments of writing.

Flores: Are you excited about what’s next? Do you have any projects that you're working on that you’d like to share?

Cerpa: I'm working on a third book right now and it’s going well. I did a lot of writing over the summer, and over the past two or three years I;ve actually done a wild amount of writing. So much that it has become unwieldy, I would say. I’m looking back and seeing what I have inside of this third book.

Andrés Cerpa is the author of The Vault, longlisted for the 2021 National Book Award in Poetry; and Bicycle in a Ransacked City: An Elegy, both from Alice James Books. He was raised in Staten Island, New York. Twitter: @_AndresCerpa

Rebeca Abidail Flores is a Salvadoreña and Mexican-American writer and visual artist from Fresno, California. She is interested in how ideas of work and play interact with culture and community. Rebeca has been a fellow in the Laureate Lab Visual Wordist Studio under Juan Felipe Herrera, and a curatorial partnerships associate at SOMArts. She holds an MFA from the University of San Francisco. Twitter: @becafloress