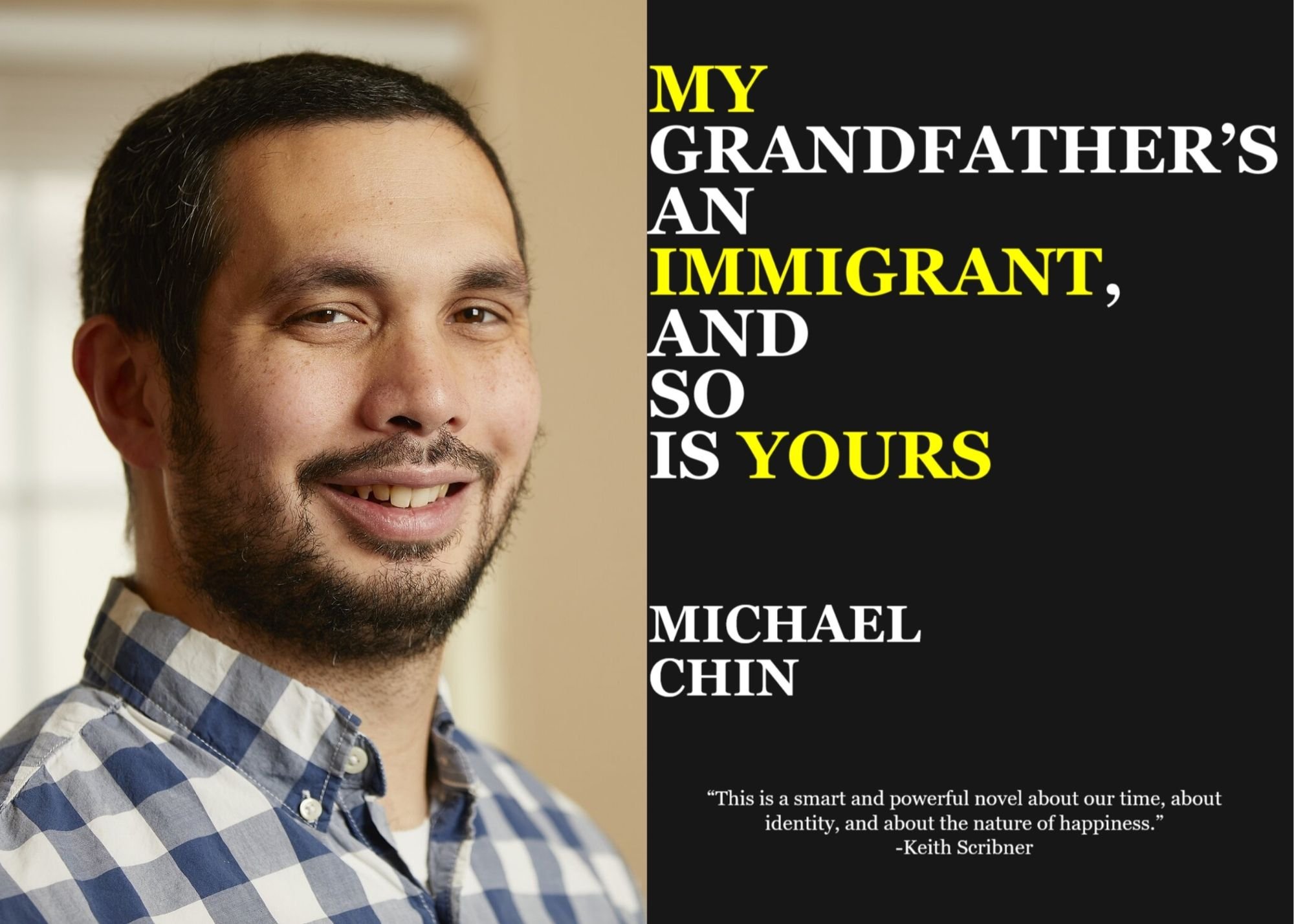

Michael Chin is the author of three short story collections, The Long Way Home (Cowboy Jamboree Press, 2020), Circus Folk (Hoot ‘n’ Waddle, 2019), You Might Forget the Sky was Ever Blue (Duck Lake Books, 2019), as well as three chapbooks of flash, poetry, and essays. His debut novel, My Grandfather’s an Immigrant and So Is Yours, published in September 2021 by Cowboy Jamboree Press, recounts the experiences of Billy Chen, a half-white, half-Chinese high school senior who considers his identity, community, and belonging among the tumultuous backdrop of the 2016 election cycle.

In an email interview, Michael and I discussed the observational narrator, writing third-generation immigrant identity, and the intertwining of the personal and the political for better understanding our world.

Mialise Carney: Throughout your novel, there is a focus on the negotiations between belonging and otherness in small-town America, especially related to race, ethnicity, and immigration. Main character Billy Chen lives in a mostly white, conservative town in New York state and grapples with being treated as an outsider in the community because of his half-Chinese heritage. What interested you in writing about this topic, and how did you come to the title?

Michael Chin: I’ve been writing about Shermantown—the fictitious town where most of the novel is set—for quite some time. It started as a stand-in for my own hometown, then began absorbing interesting tidbits I heard from other people about the places they were from, and evolving further as I imagined the place, creating more purely fictional elements that have served different stories. There’s an old glove factory that put half the town out of work when it went under but left the surrounding area smelling like leather. There’s a riverfront shopping district, but the river has mostly dried to a trickle by the time it reaches Shermantown. There’s a mental hospital at the top of a hill overlooking the town that factors into “Answer Woman,” the story I published in The Normal School back in 2016.

The novel, like its setting, is mostly fictitious, but definitely draws from autobiographical elements. I grew up half-Chinese in my own small city in fairly conservative upstate New York. I hadn’t previously written a great deal about that element of my life experience or identity, but in 2017, as public debate reached a fever pitch during the first year of the Trump presidency, I found myself called to tell a story that paired my personal past with the collective present moment. (I should also note that my wife and I were expecting as the pieces of this story took shape in my mind; I think knowing my son was on the way also galvanized me to revisit parts of my own boyhood.)

I was at the gym one day, reading an article on my phone calling out Trump and a number of conservative political figures and commentators for their own statuses as the children or grandchildren of immigrants. I have a Chinese grandmother and late grandfather who were immigrants, too, and the title My Grandfather’s an Immigrant, and So is Yours came to me as a prospective essay title. I consider myself much more experienced and skilled in the craft of fiction than creative nonfiction, and so the essay ideas soon merged with the novel ideas and the concept of the book really came together from there. After a cooling off period—most notably, the period when my son was born, as we adapted to life as first-time parents—I started writing with a fervor, mostly while my son was sleeping under my care. The first draft came together over that spring semester of 2018, alternately drafting on my laptop, my phone, scraps of paper—whatever I could reach when my son was, often as not, asleep on top of one of my arms.

Carney: I was about Billy’s age during 2016 and I think you captured the experience of coming of age during that election cycle so accurately—the assumption that everything would be fine because it always has been and then the world-shattering realization that it’s not, which parallels the reality of becoming an adult so well. What interested you about writing the experience of coming of age during the 2016 election?

Chin: I’m so glad these pieces came across as authentic to someone who was at a similar point in life to Billy! A big part of what I tapped into was my own experience as I was closer to Billy’s age for the 2000 election, in which Bush-Gore felt impossibly contentious and controversial—little could we have known where the world was heading.

In the end, a novel so concerned with matters of identity, and specifically ethnicity and the cultural inheritance that comes with being a third-generation immigrant, felt like it couldn’t help but reckon with the Trump campaign and administration. On a practical level, I could only write in the past tense in an honest and informed way about the campaign and opening stages of the presidency, given the timing of when I wrote the book. Beyond that, though, I think your questions capture precisely what I was reaching for. The personal and political are always intertwined at some level, and I think they’re often best understood as a filter or lens on one another. Here, we have twin experiences of worlds irrevocably changing, maybe fracturing, and the quandary of how life will possibly go on.

Carney: In this novel, you grapple with many complex social issues, especially from the perspective of a young man who is trying to understand his relationship to these experiences—racial profiling, micro-aggressions, school shootings, police brutality, coming out, sexual assault, consent, and mental illness, among others. How did you navigate giving space to each of these issues, especially from the perspective of an observational narrator who watches, rather than experiences, much of it happening to other people?

Chin: This is such an astute reading of Billy’s place within the novel, and I’m appreciative of your thoughtful perspective on it! I wanted this book to capture a snapshot of Billy’s life, but also a snapshot of the broader world he’s living in. While none of the social issues and sources of trauma you reference are truly new, I know I hardly thought about most of the ones that didn’t directly affect me until more recently, as they gained traction in the media and public discourse, and perhaps as I grew a bit more mature and aware of my own privileges and the world around me.

So, a part of their inclusion is to highlight the challenges of coming of age amidst a more socially conscious world, but also, similar to the backdrop of the 2016 presidential election, to paint a fuller story of the moment Billy comes of age within.

Carney: Billy recounts the story of his life and last year in high school toward an unnamed “you” he meets later in college throughout this novel. The reader receives glimpses about her life and relationship to Billy throughout the narrative, especially how she differs from the secluded Shermantown that Billy grew up in. Could you talk a little bit about the significance of having Billy recount his experiences to this unnamed “you”?

Chin: The “you” started out as an extension of the title, which I honestly wasn’t sure if I’d be able to keep given the conventional wisdom around not using “you,” and the seams being a bit too visible when it came to me trying to play with the line between “you” as a character and “you” as a direct call to the reader.

By the time I’d finished the first draft and another couple passes at revision, “you” had become a better-defined character in her own right. From there, the feedback from my initial set of readers came back pretty uniformly that they liked “you,” but she wasn’t on the page enough, so she grew progressively more present in the drafts to follow.

Ultimately, I feel as though the “you” offers the reason for the telling. I don’t consider this a very conventional novel in terms of story structure, and over the iterative process of drafting, I came around to the idea of this book being a lot like the storytelling I would do in early romantic relationships, when I wanted so badly to share my whole whole world with this person who felt vitally important to me, who I couldn’t wait to have fully immersed in my life and the world I’d known. So, the “you” becomes the reason for Billy to reflect upon his hometown, his youth, and most particularly the past year and a half or so of his life.

Carney: One aspect I found interesting about your novel is the role of the internet. I haven’t read a lot of stories that integrate social media into the everyday life of characters in an authentic way, from stressing over Facebook friend’s requests to how Billy’s mother writes Buzzfeed-esque lists as a way to communicate with her son. How did you decide to utilize the internet and social media in your story, and why was it important as a way for the mother to communicate with Billy?

Chin: The internet and social media are such integral parts of so many of our lives that I tend to feel like most contemporary literature set in contemporary times organically ought to include it (or else have some real intentionality in not doing so). I’m grateful that social media didn’t exist (at least in any of its modern forms) when I was in high school, but a lot of Billy’s interactions with Facebook mirror how I imagine I might have approached it had it been a part of my world at that stage of life.

The clickbait lists were in no small part on my mind because I’ve authored that kind of content myself on a freelance basis off and on over the years to help make ends meet. In applying the job to Billy’s mom, though, it became a way, too, of exploring a modern parenting relationship and the ways in which—more generally—I think a lot of us write a lot of things with vague intentions the words are reaching a specific audience. It’s not the most direct or necessarily healthiest way for a mother and son to communicate, but as the book goes on, I think of the lists as one of the main ways this mother stays in communication with her teenage son.

Carney: This novel has a nostalgic tone and reminded me of many classic coming-of-age stories I read as a teenager, especially the eclectic friend group which was reminiscent of The Perks of Being a Wallflower. What were some of your influences for this novel, literary or otherwise?

Chin: I’m definitely a sucker for coming-of-age stories myself. One of my earliest literary influences was John Irving whose most successful novels tended to span lifetimes; maybe it’s a function of reading them in my own teenage years, but I gravitated to the teenage parts of them, capturing simultaneous sensations of how awkward every moment can be, but also how electric it is to enter a stage of independence with first loves, leaving home, figuring out a place in the world, etc. This attraction to coming-of-age narratives crosses over to my favorite TV shows, Buffy the Vampire Slayer and My So-Called Life, each of which achieve some of their greatest successes in striking a balance between taking their teenage characters seriously, but also not shying away from the absurdities of being that age and simultaneously broaching adult responsibility and realizing how ill-equipped you really are for it. I think the sensibilities of these shows are embedded in a lot of my own writing about younger people.

I’d be remiss not to note that I’m also someone who has had the same set of three closest friends for about twenty years, a bond that’s in no small part emulated in the friendships depicted in this book. Each time we meet up there’s some sensation of entering a time machine back to who we all were when we were around eighteen years old—for better and for worse—and I think I’ll always hold onto some nostalgia about that time in my life.

Carney: You have published several story collections in the last few years as well as three chapbooks of flash, poetry, and essays. Could you tell me a little bit about your writing process, especially across genres?

Chin: I consider my greatest strengths as a writer to be that I’m a prolific idea generator and churn out first drafts quickly and with confidence. That’s counter-balanced by the fact that I drag my feet and am instinctually a bit lazy when it comes to revision. It’s a testament to my mentors and friends in writing—particularly my MFA cohort (and surrounding cohorts) from Oregon State University who have, time and again, “kept me honest” in that regard—offering sound feedback and helping me recognize where projects still need work.

I work on my writing almost every day, but between teaching full-time and family life, it’s usually not for more than half an hour each day. I typically try to write as early in the day as I’m able, because I’ve come to recognize that it’s easy for writing to slip to the bottom of the to-do list if I don’t tend to it ahead of more practical things I’m supposed to do like answering student emails or doing the dishes. I hope to have more time to write someday, though I do also think there’s value in clicking save and closing a file while I’m still excited and want to do more, to keep that momentum rolling from one day to the next.

Carney: What’s next for you?

Chin: As for now, I have multiple book projects in different stages—one I’m actively sending out into the world, others in different states of drafting and revision. I’m definitely most at home in the fiction world, and all of the well-defined projects I have meaningfully in the works are in that genre. I’ve come to embrace not knowing exactly what’s next in terms of which project will be done when or see the light of day first (or at all). I’m staying busy, though, and am confident I’ll have more words out in the world before long!

Michael Chin was born and raised in Utica, New York and currently lives in Las Vegas with his wife and son. His debut novel, My Grandfather’s an Immigrant and So is Yours (Cowboy Jamboree Press) came out in 2021, and he is the author of three previous full-length short story collections. Find him online at miketchin.com and follow him on Twitter @miketchin.

Mialise Carney is a writer and MFA student at California State University, Fresno. She is an editor at The Normal School, and her writing has appeared in Hobart, Maudlin House, and The Boiler, among others. Read more of her work at mialisecarney.com.