I am eating myself, slowly, from the outside in. Salted skin and blood. I gnaw my nails, chew the strings of flesh that peel from the edges of my fingers. A crescent moon of nail, bitten free, orbits my always restless tongue. My nails beds swell angry and red. I hide my hands in public—except for when I bring fingers to mouth again.

“What do you have to be sad about?” my younger brother asks me.

I have been eating myself for as long as I can remember. Perhaps from the womb. At night, I sleep with my thumb fisted and pressed against my lips, soothed by the smell of my own flesh. There is a picture of me on the sidelines of the soccer field—ten years old—listening to my coach with my teammates. Our uniform is yellow and green, and my mother has sewn puffy yellow wings to a bright green headband that I wear below my high ponytail. Named the Hickam Hustlers, we are fast.

In the photo, my hands are in my mouth.

“I wanted to show you what you look like,” Mrs. K, a soccer mother, says to me when she hands me the developed photo a week later. “See how unattractive you are when you bite your nails?” She does not call me a monster or yellow-winged demon, but she doesn’t have to. I know what it means to be ugly, to do ugly things.

Sometimes, often, I draw blood. Then I suck the metallic beads like a vampire, lick the line of red.

Small bits of flesh and drops of blood are ingested at the traffic light while I wait for green.

My advice to you: Don’t write memoir.

When my boys were babies, I ate their fingernails too. I swallowed their soft moon nails with joy, returning them in bits to my belly. My nails leave my body with regret—holding tight against the tearing, blood to mark the trail. Their crescent points, sharp and painful in my throat, shred in the passing. Consuming my sons, though, was like eating taffy, warm and soft and satisfying like the sea.

You will have all these philosophical ideas about memory. In fact, you will write them into your book—all this about slipperiness of the past, little t and big T truth. Horseshit. Neither self nor family goes down easily. Even your babies grow older and become so much harder to swallow.

When I was twenty-two, I grew my nails long. The only time in my entire life when I did not bite them. I painted them pink, filed them daily with an emery board. I could not recognize my hands; they were a stranger’s. I spent long periods of time just gazing at my pinkie finger as if it were a lover. I had a lover then. He was the reason I had stopped biting my nails. He had proposed to me one night—down on a knee, fancy dinner, everything arranged into a scene worth telling—and placed a diamond solitaire on my ring finger. He had spent three month’s salary on the ring—or at least that is what he told me—he lied a lot—about fourteen-carat gold and the women he did not fuck.

People would be looking at my hands, so I stopped eating them for a time.

I would like to say that when he left me four years later for another woman—her nails long and curved like her blonde hair and round breasts—that I returned to eating my own flesh, but it was long before then—maybe just after the wedding—the one—my own that is—that I left early because my lying new husband was tired and wanted to be done.

“What do you have to be sad about?” my younger brother asks me. He thinks my memoir is about him. I am sure my parents believe that any fault is their own. But I am the one chewing.

In high school, I read in Seventeen magazine that you could paint your nails with Tabasco sauce to stop the gnawing.

In college, I coated the small squares of nail that I had not managed to consume with a clear flavored polish that tasted bitter in my mouth.

No matter. Bitterness and pain were easily accepted in exchange for the pleasure of tearing. The ripping created a staying, a staving off; the nibbling, a ceasing, momentarily, of the rest.

Little makes me happier than when one of my nails—always hopeful, fingernails, always trying to grow again, even in hostile conditions—grows enough that I can peel it off, seam of blood, and then to mouth.

Sometimes flesh remains on the nail.

Sometimes the flesh is only to be consumed as a hangnail.

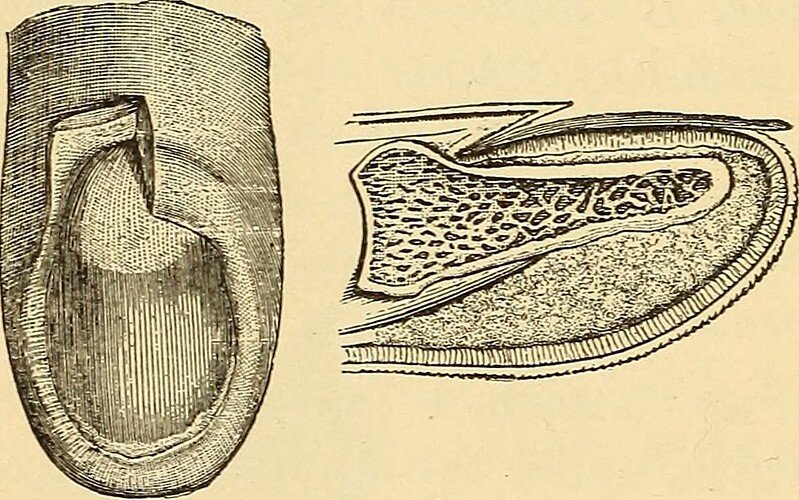

Medically, a hangnail is the tearing of the eponychium, the thickened flesh alongside the fingernail or toenail. Eponychium comes to us from the Greek—epy, on, and onchium, little claw—the flesh surrounding and protecting our claws. The eponychium prevents infection, which explains why the flesh around my nails grows angry and red. It is not safe from me.

Nails are leftover claws—a means of defense for other mammals but domesticated on our bodies. They are made from the same material as horns and hooves and hair, and the reason for their continued existence remains debated by scientists. After all, we do not need claws. We have nothing to fear.

Dave Eggers writes toward the end of A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius that memoir is always an act of cannibalism. You must consume others in order to write about yourself. Mother, father, aunt, brothers, into your maw.

Or at least that is my memory of that memoir. But memory is an unstable and tricky thing. What is true for one person may not be true for another.

(That’s the kind of horseshit I mean.)

I could suggest that the tearing of nail from skin—bright pain, short-lived but so pleasurable—reminds me that I am alive. It roots me to the present. It is real and true—pain is. Real and true in a way that language and memory are not.

But I would be lying. To eat yourself alive is not affirming. In fact, onychophagia (from the Greek for “devouring your claws” or sacrificing what you need for protection) is on the spectrum of OCD. Pathological grooming.

Does writing—by its very need to nail down the chaos of experience to the syntax of sentence—always entail a winnowing?

I cannot stop biting my nails. I don’t want to. I am tired of trying to be good.

I eat myself more than I eat food. Most days, I wait to see how long I can go before I have to eat something other than my own flesh. I love the hollow feel of my belly, the knowledge that I have taken nothing in.

I am very skinny.

When hangnails become infected, it is called paronychia. The infection can cause deformations in the nail itself (see the index finger of my left hand for an example). Treatment for paronychia includes lancing the swollen areas. This doubling of damage—first the trauma of the tear, then the trauma of infection—would be akin to not only writing about your aunt’s childhood bedroom but also revealing how she suffered sexual abuse at the hands of her father.

Paronychia is caused by trauma to the cuticle—from all the biting. Every time I bring hand to mouth I traumatize my body—pen to page, fingers to key—but then isn’t all writing a kind of violence? Not to get too dramatic, but what does “I” even mean? Who exactly has been distilled into that slender, hollow-bodied line?

This past semester a student of mine wrote about the ferocity of caterpillars, how they behead themselves as a final act in chrysalis. Before emerging as a butterfly, they must digest themselves—eat themselves from the head down. What gets consumed—the flesh—becomes the butterfly—cells programmed at birth to sacrifice themselves at the appropriate moment.

I know, nice metaphor: you must consume the world around you, your very self, in order to make art. Beauty.

But my fingers swell and bleed, and so many in my family have been hurt. By me. Not a lot of butterflies flitting about.

I have shown that I can stop biting my nails—remember those pretty pink-tipped fingers belonging to the stranger—but I don’t. I just keep eating.

I am no caterpillar, no butterfly. I could claim some pretentious need to make art. I could say the pain is what it takes to find the truth, so suck it up. But I see you, nibbling only. You haven’t even fully ripped off your first nail. Do you know the pressure your mouth must maintain to keep the blood coming? Do I tell you to get the Tabasco before it is too late?

I am ashamed of my hands, my habit, my constant craving to devour what matters most. And the irony does not escape me that I starve my body while I feed on myself and family.

I am not alone. Both the praying mantis and the black widow often eat their partners after mating. Sand tiger sharks and tiger salamanders devour their own as well, as do more domesticated animals like chickens and hamsters. The most shocking example of animal cannibalism, though, might be the chimpanzee—a mammal with whom we share an enormous percentage of our DNA. In the late 1970s, Jane Goodall recorded many instances of a female chimpanzee eating her own babies or those of others. What makes this example so remarkable is that scientists have yet to explain why. Instances of cannibalism in other species can be tied to specific evolutionary reasons or needs but not with the chimpanzee. The violence just happens. Goodall writes, "It is sobering that our new awareness of chimpanzee violence compels us to acknowledge that these ape cousins of ours are even more similar to humans than we thought before." It is our nature to consume.

Yet, of my wider circle of close friends and family, I am the only one to publish a book-length memoir.

And the vast majority of adults do not chew their nails.

So clearly not everyone is devouring what is sacred to them.

“What do you have to be sad about?” my younger brother asks me.

Doctors can determine your overall health by examining your nails. They can read your cuticles, your nail beds, and name your sicknesses.

If you see a clear path out of here, please let me know.

Perhaps it is our nature to consume, yet I am alone in my devouring. As a memoirist, have I eaten more than my fair share?

“Self Pity, thy name is Sinor” writes a reviewer on Amazon about my memoir.

What if all this devouring of self and family, the bleeding, the ripping, the tearing, the swelling, is not art but vanity? A sick pathology, a disease.

That is the fear of course. It is what you work so hard against.

You begin to nibble at the edge of the just-growing nail, try to catch a corner, some purchase, a place to stand. The nail resists the pull from flesh, spots of blood trace the site of trauma, but the nail does come, and the pain is temporary, and you are trying so hard to be careful, to contain the pain to a specific site, your body alone, you are trying so hard, and tearing so carefully, and sucking every drop of blood, removing every trace, thinking that maybe the scoring is clean. Nail to mouth, jagged crescent tips against cheek and then the long sharp journey down the esophagus. No one has seen.

But a week later, the photo arrives, proof of your monstrousness. Cannibal that you are.

Or, a week later, an email saying that a reader has devoured your words in a weekend and she has been transformed: caterpillar to butterfly.

Either way, you can’t stop. The habit is so old, the act so familiar, and your nails keep on growing. Here, catch the edge and tear.

Jennifer Sinor is the author of several books, including Letters Like the Day: On Reading Georgia O’Keeffe and the memoir Ordinary Trauma. Her forthcoming essay collection, Sky Songs: Meditations on Loving a Broken World, will appear in the fall of 2020 from the University of Nebraska Press, and her essays have been published in many literary journals including The American Scholar, Utne, Creative Nonfiction, and Gulf Coast. The recipient of the Stipend in American Modernism as well as nominations for the National Magazine Award and the Pushcart Prize, Jennifer teaches creative writing at Utah State University where she is a professor of English. She lives in Logan with her husband, poet Michael Sowder, and her two sons.

Photo by Internet Archive Book Images on Foter.com / No known copyright restrictions