There are two things I remember about rich kids and poor kids. The rich kids drank Coca-Cola and rooted for San Francisco. The poor kids drank Pepsi and rooted for Oakland.

-

My mother always says: I wish you would have known your father before the accident.

-

My brother and I are at home watching the third game of the 1989 World Series just like everyone else. The A’s won the first two 5-0 and 5-1 respectively and everyone knows the Giants don’t have a chance. This is our year.

The teams are warming up when the screen of the television flashes yellow and purple before fuzzing out to gray as Al Michaels interrupts Tim McCarver and says, “I tell you what, I think we’re having an earth—” and with that the broadcast fails. The screen flips to a green ABC background with the words World Series plastered across it. We feel a rumble 120 miles away from Candlestick Park in our little town of less than 5,000 people.

-

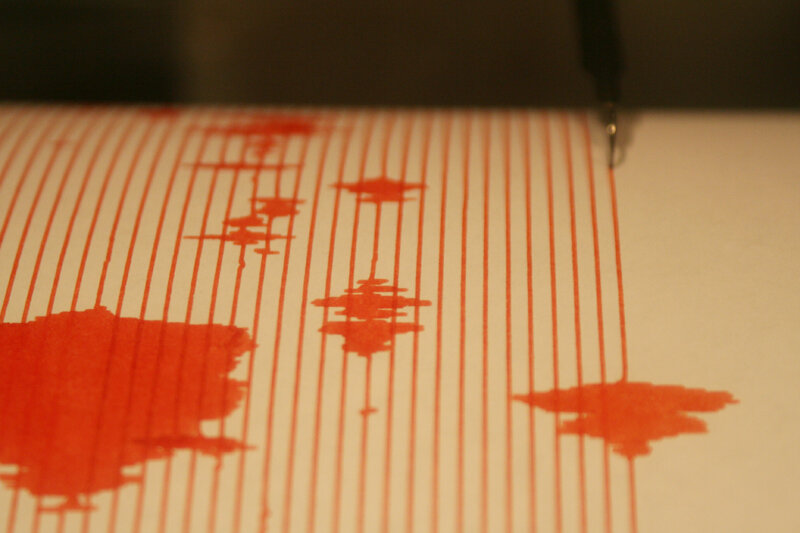

This is around the time when I learn that there are other kinds of quakes. Those not just caused by the earth shifting, but by internal seismic shifts in a person’s psyche known as a psychotic break. In some cases, stress from traumatic events can be stored within a person and stuck inside until the force becomes too great, sending shockwaves through your grip on reality. These waves affect those nearest the epicenter the most. But just like with physical distance, these ripples can be carried across time, even generations.

-

My father’s accident occurred in 1972, a decade before I was born. A 30-foot fall to concrete crushed the bones of my father’s body. The radiuses jutted out four and six inches from where they belonged in my father’s arms. His hip bone eight inches out of the body. His back broken in more than a dozen places. A man who witnessed the fall and visited my father in the hospital was unable to shed the image of a plummeting man from his mind. This witness said, “I didn’t think there was any way you could survive a fall like that.” How they put my father back together is a mystery, how he ever walked again, and how the arm that broke his fall wasn’t amputated are all small miracles. But as my mother says, he was never the same. How could he be? Events like these change the course of a person’s history.

-

Part of the Bay Bridge caves in and the Marina catches fire. The Cypress Street Viaduct collapses, killing forty-two people. All hell breaks loose and it happens on live television. Emergency personnel pull people covered in blood from collapsed buildings. The debris pins people underneath. Irretrievable people. News anchors urge citizens to turn off their electricity and gas while staff in the background run back and forth in panic.

My father grips a Budweiser and smashes the can before tossing it towards the kitchen. It rattles across the linoleum where segments have been pulled away revealing patches of plywood exposed and vulnerable to rot. Drops of beer soak into the floor my mother just cleaned. My father tells my brother and I to go to our rooms, but we are glued to the very images he doesn’t want us to witness. Deep down, he wants to shield us, protect us from an unsafe world outside the walls of our home.

-

The truth is, we rarely had Pepsi. We drank generic sodas and got the cool red, white, and blue can only on special occasions accompanied by my mother’s tacos. A white trash version that involved ground beef and fried flour tortillas. Iceberg lettuce. Maybe you had a version too and that’s cool, something we can joke about—but I’m telling you, unless you were a poor kid, you don’t totally get it. Most of the time my father was not home for these tacos. My mother kept three or four rolled up on a paper plate in the microwave for when my father finally came home smelling of generic beer and cheap whiskey. Budweiser too was only around when my father had picked up an especially well-paying job.

My mother tells my father to pick the can up and clean the spill. My brother, four years older than myself, sneers at my father. “Yeah, dad,” he says.

I am gobsmacked. One does not talk back to my father.

-

A psychotic break is not an abrupt chasm in a person. In fact, the term isn’t used that much anymore. Psychosis usually comes with a notable decline, with various symptoms occurring sometimes for years. It’s important to try to recognize the signs before a crisis emerges. My father believed that people, his closest friends, were sneaking around and up on him. He believed my brother and I were stealing things, hiding things from him. The one time my brother called the cops, he accused my mother of sleeping with the man who asked her if she wanted to press charges. She did not.

-

Many earthquakes have foreshocks, warnings of what might be coming. The Loma Prieta earthquake had two. One in June 1988. And one in August 1989. Unfortunately, one can only identify a small earthquake as a foreshock retrospectively. In California, each earthquake has only a 6% chance of being followed by a larger more devastating quake and the state has too many earthquakes to think in foreshadowing terms. In fact, every year, more than 10,000 earthquakes occur in Southern California alone. Potentially many, many more. But most are too small to be felt. It would drive a city mad to assume each earthquake could be followed by something worse. You just have to hope for the best.

-

The room is silent for a moment except for the footage of the disaster rolling in the background. And just like that. Snap. My father lunges towards my brother, repeating for him to get to his goddamn room. I cannot see my father’s face, but I know what my brother must see inches from his own. Reddened skin. Distended veins. And sputters of spit flying toward him. When my brother freezes in eleven-year-old fear, my father shouts, “Move your ass!” Which he does. Maybe it’s because my brother runs that my father cannot help but chase his prey. My brother slams the door behind himself in time to prevent my father from entering. My brother may feel that he is safe behind the locked door. But only for a moment.

-

1989 was also the year the Berlin Wall fell on November 9th. Three and half weeks after the Loma Prieta earthquake, Peter Jennings describes the news as sending “shockwaves” through Eastern Europe. Images of celebrating Germans, both East and West, flood the television. I watched the news clips on my laptop in New Orleans twenty-two years after they occurred. I’d been hired by an architect who was working in Berlin in 1961 when the wall went up. He designed the first hospital in the city after the end of the war. The erection of the wall is the focal point of the book the architect hired me to write, not its fall. But something about the lives of two separate cities breaking down, spilling into one another, captivates me more.

-

The first time I experienced psychosis, I was fourteen years old. It was brought on the way it often is in adolescence: drug use. I was smoking weed that had been laced with PCP and essentially lost 90% of my contact with reality. A small tether to the here and now actually made me feel crazier: to suddenly have the false world crack open into what I perceived as real only exacerbated the long stretches where I was somewhere else entirely. I did not know it until weeks later that “honey dipped” was code for angel dust to the person rolling the blunt. I naïvely believed honey was actually involved. I had flashbacks for months and panic attacks for over a decade afterwards. It felt as though the walls of reality might crumble down at any moment and I had to fight to keep myself from falling apart with them.

-

My mother chases my father, afraid of what he might do. She tugs at his arm, pleading for him to stop. He yanks away and backhands her across her left cheek. He catches her before she hits the floor and throws her against the bedroom door. He punches holes all around her head, so that my mother appears haloed and holy in the wreckage.

-

As the fire blazes through the Marina, collapsing buildings knock out the hydrant system. Civilians aid firefighters running fire hoses towards the bay. The fireboat, the Phoenix, which had nearly been cut from the city budget, helps to save the Marina District.

-

As an adult I’ve become so privileged that I’ve traveled to Mexico three times. Real, authentic tacos are one of my most favorite things in this world. But my mother’s tacos—those kind of awful, but amazing bastardizations are something else altogether. They hold in them such a sad sweetness. The possibility of my childhood being taken from me. And so when you tell me we should have a white trash taco party, I’m with you, like fully on board, and yet so far apart, it’s as though we’ll never meet.

-

The second time I lost contact with reality, my boss, the architect, had died. He was the first person to pay me for my writing. When others questioned my role, he defended me. He told me I was a talented writer. It was something my own father could only ever tell me when he knew he was dying. Before that it was always dismissed as a waste of time. My father complimenting my writing was his greatest attempt to bridge the distance between us. To knock down the barriers he himself had built there. Of course, this was also accompanied by the idea that we should write a book together about all of his conspiracy theories.

After the architect’s death, the book I was writing, The Walls of Berlin, got canned. A year of my life, a friendship, and an identity I badly needed disintegrated. The interior walls I’d erected as a defense against the outside world came crashing down and the parts of myself I’d avoided for decades came rushing to the forefront of my psyche. Just like the East Germans demanding access to the West, the separate sides of myself converged in a way I could not make sense of. The reunification too painful for comprehension.

At home I hid in my bedroom chewing on my pillow or articles of clothing on the floor to stifle the sound of my howls. These beastly cries were accompanied by uncontrollable shaking, body-breaking tremors, what I learned later are referred to as crying jags. It’s true that this may not fall under the label of psychosis. But who can say? Seeing a therapist was not a luxury I could afford until many years later.

-

Sometimes you shame me for saying I was ever poor. You remind me that we always had food and a roof over our heads; what more could you want? I fall silent, because of course you are right, and I was never trying to imply otherwise.

-

The fall of the Berlin wall, at least its timing, occurred due to a mistake during a press conference. When asked when the new rules regarding East Germans travelling west would occur, a confused spokesperson, Guenter Schabowski, stumbled and replied, “Uh…Immediately.” What followed was described as a mass exodus.

-

The lack of money wasn’t that bad. The abuse by my father wasn’t that bad. And that’s what I said for decades, if I said anything at all. If I’d been ridiculous enough to have a self-help mantra that’s what it would have been. If it came up, I quickly dismissed it as: meh, it wasn’t that bad. And it wasn’t, not really, right? For a long while, I became one of those tough badass bitches who drinks too much whiskey, smokes indoors, and fucks men—sometimes women—just to discard them into friends she can call up anytime she wants, just to break them again. I’m not going to lie about this, I enjoyed all of it. The detachment and air of coolness I projected was more addictive than any substance I ever ingested. One time a close friend told me my mental instability was too much for her to handle. I admit, that was hard to hear. So I drank more. And felt less.

-

It’s estimated that the earthquake caused six to ten billion dollars in damages. In addition to the sixty-three people who died, the Loma Prieta earthquake injured over 3,700 others and 1.4 million people lost power. However, it’s also speculated that had it not been for the World Series, the death toll would have been significantly higher. The quake hit at five after five – during rush hour traffic – but because most people had left work early to watch the game, the roads held less commuters than normal.

-

Eventually, at least for some people, stored trauma can catch up with you, break you wide open, and depending on any number of factors, you might never be the same. You might not be able to return to being that badass bitch. Some people might say that’s a good thing. You might become fragile. You might experience life from that point forward as though your insides are on your outside. Exposed and vulnerable to rot. Susceptible to silencing, even though for the first time you’re ready to share a story about who you are and where you are from. You might be willing to admit the deep longing you have for flour tacos fried in vegetable oil and stuffed with ground beef. Non-organic—fed terrible corn products—ensuring the demise of the world through climate change—beef. You might want to tell people about it so that they might understand what those tacos mean to you. You might want to be seen for who you really are and not the socially conscious person you pass for most days. Despite not having had those tacos in years, the stain of where you are from can never be washed away. You are your father’s daughter. And that makes you the monster. God forbid you ever admit that. God forbid that you admit your best self might have been that self-destructive girl. Oh, how you miss her!

-

The Loma Prieta earthquake took its name from the nearby range in the Santa Cruz mountains. It registered as a 6.9 on the Richter scale. The largest earthquake in California since 1902. It was a beautiful fall day in October—thirty years ago. But if I’m being honest, I don’t really remember the Battle of the Bay nor the earthquake that shook two cities. I don’t remember the fall of the Berlin Wall. Not really. I don’t remember these pinnacle moments in time nor those that followed like the other kids do. I remember my father breaking down the bedroom door with his bare hands and slinging it into the living room before me. I remember not recognizing the madman jumping up and down on the door screaming at all of us to get the fuck out. I remember being piled into my mother’s car with my brother and driving not ten minutes before turning around and going back. And I remember the look on my mother’s face, swollen and pink, as she says we can’t afford to leave him, that she can’t take care of us on her own, but that everything will be ok.

-

Sometimes my partner catches me talking to you. He says affectionately, “what are you muttering about?” or “who are you talking to?” And briefly, for a moment, it pulls me back from the ongoing conversation I’m always having with you about this or that. I’m embarrassed because I had no idea I was speaking out loud. I smile and tell him no one. Just myself, I say. But you’re more than that, aren’t you?

Lee Ware is a writer and editor living in Portland, Oregon. Her essays and short stories have appeared in Green Mountains Review, Oregon Humanities (Beyond the Margins), Propeller, Connotation Press, Ekphrastic Review, and elsewhere. She was the 2019 recipient of the Tom and Phyllis Burnam Award for fiction. Lee is currently pursuing her MFA at Portland State University where she teaches composition, serves as the nonfiction editor for Portland Review, and co-curates the Filament Reading Series. She is currently working on a novel and a collection of essays.

Photo by viviandnguyen_ on Foter.com / CC BY-NC-ND