We will sidestep, and to the final smirk

Dally the doom of that inevitable thumb

Hart Crane, “Chaplinesque”

Dawn. White serif letters on a black background. An empty stretch of highway. Telephone poles. Scrubby plants. Short desert trees. The Little Tramp—with mustache, cane, and baggy suit—sits by the side of the road fanning his feet with his hat. Beside him the Gamine, a beautiful street-urchin girl, ties a knapsack, gazing forlorn into the distance. Suddenly she falls in despair, head in the crook of her elbow. The Tramp moves over, touches her arm. She looks into the camera, speaks. “What's the point of trying?” The letters vibrate in black-and-white.

It was at the end of Charlie Chaplin's Modern Times that I'm pretty sure I heard Harris Mirkin crying. We were in a dark room in the university library. As the scene unfolded, from somewhere near the back of the room, I heard a few muffled sobs. Five or six seats away from me was Dr. Mirkin. I could see his length of white hair spilling from the side of his head. His wrinkled face was obscured by the dark room and the body of another student sitting next to him. I thought maybe he had suffered a strange and violent sneeze. I looked back at the film.

The Little Tramp and the Gamine begin down the road, toward us, to a sweet and aching tune played by reedy strings. As they reach the camera, the Tramp stops to make an adjustment. He draws two fingers across his lips to the corners of his mouth. “Smile!” Grinning, or maybe grimacing, they go tromping up the highway. As the shot cuts to show them from behind, there is a renewed levity to their steps, and we see a set of grainy black-and-white hills in the misty distance.

The scene recalls the California half-desert where I grew up: Paso Robles, thirty miles inland. Homeschooled, I spent my days outside in that semi-arid climate. My mom worked in the sun, planting a wildflower garden around which hummingbirds and swallowtail butterflies hovered. My dad built a fence with a scalloped top like curling waves to keep the dog in the yard. (The dog, assessing for a couple minutes, jumped it in a single bound.) They added French doors, a flagstone patio, a grape trellis. Soon, though, we were moving back to Kansas City. There were many reasons, not the least of which was the considerable debt my parents had taken on to make that home beautiful, leaving them little choice but sell it.

The TV we had then was like the one in the schoolroom—a big black box, cathode-ray tube. As a child, I would put my hands near the screen to feel the static electricity that had built up—an invisible barrier, fuzzy, like a blanket. There is an invisible barrier between me and that time now.

From the back of the room, I heard Mirkin's yelping sob again. An odd sound. It was not exactly a cough, and almost a laugh. But I don't think that's what it was. I say yelping, because I can recall how in that moment it reminded me of the sound my old, fence-jumping dog had made a couple months before, when he started having seizures. His sobs were like that, only much quieter.

I could not see Mirkin. Between us someone had leaned back. I did not get up, did not tap his shoulder and say, Are you feeling okay professor? No one else did either. They did not even look over.

The credits rolled. Someone clicked a light switch. We all blinked in the glare.

In the light, Mirkin was restored to his usual self—a funny older teacher with a wicked ability to keep students guessing. They would come to remember him as That Professor Who Looked Like Albert Einstein: his white hair falling in two snowy shocks, like the deflated wig of a clown; his white mustache fanned-out and hanging crooked over his mouth—which was also crooked, and would lift to the right side of his face when he lectured, half-smiling. He was endearingly odd. Einstein, bent through a funhouse mirror.

As the students left, Mirkin was trying to find somebody to pawn food off on. He had brought a large bag of buttered popcorn, along with plates, cups, and two or three two-liter bottles of soda. The popcorn had been distributed, but we hadn't made a dent. The sodas were easy. No one really wanted the popcorn. It was cold. The bag was large. It was more like a sack than a bag. When he finally found a student who was willing to take it, Mirkin said, “I know meals are scarce in college.” He aspirated the r in scarce, made it like an h.

I observed this because I was hanging back. I was always hanging back at the end of classes then. I could never seem to get enough time with my teachers. I was hungry for something. I wanted to stay a little longer. For information? Knowledge? Maybe it was simpler. Let's say goodbye. Or have some little ritual that meant, Thank you, Dr. Mirkin, that was a good lesson, I am your studious pupil, your words won't be forgotten. I craved the closure that such a shared moment would bring. Instead, in those days I felt the abruptness with which most classes ended: the announcement that time was up for today and we would have to bookmark our conversations there, the jarring clatter of textbooks and notebooks and binders being crammed into backpacks that were already near-bursting, the herding of forty, sixty, a hundred feet to the door. It felt like the opening of Modern Times—harsh music over an image of a clock, and then workers shoulder-to-shoulder exiting a subway stairwell, fading into a shot of sheep being funneled up a ramp. So, I lingered.

Freed of the popcorn, Mirkin practically bounced. He put his blue bicycle helmet on his head, with its little circular mirror suspended on a wire before his face. (Did the cars behind him see his cartoon face reflected in miniature off the mirror?) I cannot say what we talked about then. Maybe the next time we would meet in his office. I was not enrolled in the Modern Political Thought course which had just watched Modern Times. Rather, I was in an independent study which I shared with a graduate student in his final semester. I was only a freshman. “Sure, but you're both interested in similar things,” Mirkin had said, countering my anxiety with offhand ease.

I walked beside him towards the exit. He was shorter than me and had a bit of a funny, stumping gait. We went out the double doors and into the night. It was already dark. A cool spring evening. Across the parking lot streetlamps glowed, and the cars cruising by made distant sounds that were almost ocean-like. Mirkin swung one of his short legs over his bike easily and rode away.

∞ ∞ ∞

I may have been avoiding going home. I think I was for most of that year. I have a static image in my mind from that time that I know is a reduction of the state of my mother's health. She is curled in bed against the gray family dog. The warmth of his body eases the pain in her stomach.

She has a rectal tumor and has been assigned nine months of treatment for it. She will go through radiotherapy, surgery, and chemotherapy. She never loses her hair. Her agony is visceral, i.e., located in the viscera. She disappears into the bathroom for lengths of time, sometimes hours, it seems. She complains of how her insides are running out of her.

There were signs leading up to the diagnosis—which came one night in February, when she had stomach pain severe enough that my father insisted on taking her to the ER. She'd been having stomach aches since November. On Thanksgiving Day, I was on the couch reading Marx for Mirkin's class, while she was in bed suffering from pain that left her unable to emerge for the meal.

There were weirder signs too. The summer before her diagnosis (and before my freshman year) the cat died, a wad of cancer in his guts. A lanky orange tabby, he had warmed our laps and spilled the blood of baby rabbits whose hideous shrieks would wake me in my bedroom. He'd inhabited that space in between comfort and carnage, seeming to drip off the edge of the bed for minutes and minutes, ready to go off and kill again, but too languorous in our affection to leave. He was the sole tomcat in a litter of three kittens, all of whom were adopted. It had been one of my mom's many ways of trying to apologize for moving us across the country, away from California.

He died on the operating table. The vet said it would be cruel to wake him up. For as long as we had known him he had eaten ravenously, stayed thin. I liked how the incongruousness of his appetite and body-type matched my own. But we had noticed his crying for food becoming more insistent, constant. His form shrank. Then he had started vomiting. Weeks later he was dead.

∞ ∞ ∞

Just before my first semester I was handwringing over whether or not to take Mirkin's class, which satisfied no core requirements. To my embarrassment, my mother actually called him. Mirkin had been her teacher in the '80s, when she was working as a legal secretary, and going to school on the weekends. She recalled his sense of humor, his wry smile. “He said, 'You should always take one course just for fun,'” she said, standing in her bedroom door.

On my first day, I was nervous. A lifetime of homeschooling will do that to a person. I had been taking a class or two at the community college class for a couple years. (There, on my first day, my hands shook as we wrote short introductions of ourselves.) But I had grown comfortable with the weird band of misfortunates who found themselves at the community college. This was new. Here, I would be going full-time, with people my own age.

I sat in the third row. Mirkin sauntered in. He set his bicycle helmet on the table in the front of the classroom. There was a circular mirror dangling off the front.

He asked us to raise our hands if we were freshmen. I looked around. I was the only one.

After class, an older kid from my neighborhood recognized me. When we first moved back to Kansas City, he and another kid—my age but twice my size—used to come over to jump on my trampoline, like the kids in Paso had. Their games were rougher: Crack the egg, crack the bacon. I came in bearing rugburns, small bruises. Mom was concerned. They stopped coming over.

I was happy to see him, to have a comrade. “Oh yeah,” he said, “we'll get through this class together.” He wore a black denim jacket with political buttons. The anarchist A was unknown to me, but Buck Fush! I liked. He wasn't there for the next class, though, or any others.

Mirkin had us arrange ourselves in a U. He wanted us to see each other when we talked. If he came into class and our desks were in rows, he would say, “Is this your silent protest against the U?” Gradually I made friends. Others who talked came to sit in a bunch at the top-right arm of the U. They were: The graduate student, with whom I would later be enrolled in the independent study. In winter, after class, he'd stand outside the building and smoke and look like he was about to freeze to death. A philosophy major who wore black eyeliner, white foundation and crimson lipstick. She smoked, loved Marcus Aurelius, shared a house near campus with her boyfriend. When she invited me over, I got drunk on whiskey and ginger ale. My first friend in the class, she brought our group together. It was her idea to host a study group before midterms. She even made apple pie. I was supposed to take a piece home to my parents—my mother was not yet ill. Instead I took it home and ate it. I had to lie. After the semester ended, her father died suddenly. Her boyfriend dumped her. She dropped out. Guiltily, I distanced myself, meeting her for lunch only once at the Chinese restaurant near campus. She was full of manic intensity to be updated on my family, my life. I was reticent, unwilling to divulge much. If I mentioned my mother's illness, I downplayed it with phrases like: she'll be fine, and it's non-life-threatening. There were others: A well-dressed kid who Mirkin (mis)labeled as the resident Republican in the classroom. (“I actually voted for Obama,” he complained.) An attractive girl from Spain, with whom I never managed to have a conversation on my own—although, once we both waited for Mirkin after class. And Paul, who I ran into years later in a bar. We were both drinking, out with our own friends. “The teacher who looked like Einstein,” he said. “Yeah, I heard.”

Almost every day Mirkin rode his bike to class, a fact confirmed by the presence of the blue helmet with the mirror, sitting on the table at the head of the classroom with his satchel of books. Even in winter, unless it was horrendously cold or snowing, there it was. Sometimes in class, he sat on the table and swung his legs like a child. After class, when I was face-to-face with him in the hallways, his eyes twinkled like he knew something and I didn't. His own political opinions were hard to pin down. I would try to figure them out and get nowhere. And when he answered a question (in a way that usually led to more questions when I got back home), he would half-shrug, hold his head diagonally, and sort of flop it from side to side. One could say he took the ideas of seeing every angle, and teasing out the meaning too literally.

He was fond of unusual examples too, and he had a weird sense of humor (a word he pronounced without the r—“hum-ah”). Sometimes he perplexed us all with his New York accent.

“Say you create a Frankenstein monstah,” he said. Then, mumbling to himself, he added, “No, let's make it a bit more modern. Say you create a row-butt.”

Baffled, I looked to my friend, the girl with the crimson lipstick. In her notebook, she had drawn a grotesquely wrinkled cartoon of Mirkin.

“And the row-butt starts killing people.”

She drew a bubble coming from his lips.

“Do you bear responsibility for the killings of that row-butt?”

In the bubble she wrote, Robot!

Another time, to illustrate the short, nasty, brutish life found in Thomas Hobbes's state of nature, he said, “Say you like my bike. So you hit me over the head with a rock.”

∞ ∞ ∞

Years later, I bought a biography of Albert Einstein. I didn't read more than three pages of it. I bought it for the epigraph. (I've often thought I would be better suited to collecting epigraphs than writing the words that must follow them. Avoiding the work. Seeking the precious phrase that is the perfect complement to one's mind.)

On the epigraph page, Einstein—mustachioed, dressed in trousers and cardigan—balances on a tilting bicycle. A white shock of hair streams behind him. The shadow of his bicycle is so perfectly defined (you can almost see the spokes!) that you can tell it must have been a cloudless sunny day in Santa Barbara, California in 1933, (as the caption tells us). Below the photo, centered on the page, is a snippet from a letter Einstein wrote to his son: “Life is like riding a bicycle. To keep your balance you must keep moving.”

Now, I don't know a lot about Einstein or general relativity, but I've ridden a bike before, and it seems to me that laws of motion are everything. The moment you stop moving, stop your relentless push forward, is a bad one. The moment you say something is ended, that is the moment of death. You fall off the bike.

Suppose you are a planet, orbiting the sun. One orbit simply becomes another. That anything ends, or anything else begins is merely a human delineation, then. So why call anything complete?

∞ ∞ ∞

Mirkin brought donuts from the local bakery to his early morning final exams, and hot popcorn to film showings. Like Charlie Chaplin, he saw food as one of the inroads to the human heart. And Modern Times, like any Chaplin film, is a film about hunger. The Little Tramp is a test subject for an automated feeding gadget meant to eliminate the lunch hour. When he traps his boss's arms and legs in one of the factory's giant machines, The Tramp must hand-feed him—a celery stalk becomes a funnel for coffee, hot soup. In The Tramp's daydreams of domestic bliss, an apple tree grows ripe fruit just outside the window and a cow walks up to the kitchen door to be milked.

It takes a perceptive comedian to find laughs in the empty stomachs of the Great Depression. There are rich people who await their food angrily (the Tramp, their unfortunate waiter), and there are poor people who encounter the harshness of the law for stealing bread or a bunch of bananas. Sometimes though the laws that leave one with a pain in the gut are not societal and externalized, but individual and interior—a betrayal of the body itself.

During my mother's year in bed, the question of cause hung in the air. She had been healthy and in shape—did yoga and took dance classes. (Chaplin moves like a dancer, she said as we watched the roller-skating scene from Modern Times.) Were the witching hour bags of candy to blame, consumed with equal appetite as the black-and-white films she'd seen before on Turner Classic Movies during long nights of insomnia? Was it the aerial silks she'd taken up the year before, the strain of wrapping one's stomach in a knot and falling? Was it the doctors (as she would come to believe) and their over-treatment (zapping, slicing and chemically-poisoning) of a growth only micrometers in size? Was it random? Or cruel fate?

∞ ∞ ∞

"It's the first time the Tramp doesn't end up alone," Mirkin said in his office a few days after we watched Modern Times.

It was spring, the second semester of my freshman year. We were in Mirkin's office. On the door was an aging atlas of a world that had been flipped upside-down, so that South America and Africa were above the U.S. and Europe. It was meant to give perspective. On the shelves covering the length of one wall there were piles of books—books of philosophy, and political criticism, but also novels, plays, poetry. (More than I can remember. Their loss seems a tragedy.) Some lay horizontally on top of the ones in rows. The desk, which sat between us, was covered in books, papers, documents. We held our notebooks in our laps.

I was there with the graduate student. He was thin, and had the twitchy energy and dark, alert eyes of a small primate. He tapped his notebook with a pen, argued his points vigorously—though it was not clear, sometimes, what his points were. B.F. Skinner and Karl Marx can be combined, he seemed to be saying, they're on the same page. Mirkin dispassionately (mischievously even) offered angles of consideration.

For the independent study, we were reading Freud's Civilization and Its Discontents, and an analysis of his peers: Carl Jung, Otto Rank. We read German theorists who had tried to combine the work of Freud and Marx, and who had (quite accidentally) become heroes of the 1960s counter-culture. But there was no syllabus. Everything was ostensibly of our own design. “You're interested in Marx,” he said, with an incline of the head. “You should read Marcuse.” I wasn't really sure what our goal was. The previous semester had been much clearer with weekly quizzes, midterms, final exams. It had been ordered chronologically, from the ancient Greeks to the Modern world. We'd read Plato, Aristotle, Hobbes, Locke, Rousseau, Marx, Nietzsche. Now, we were in precarious waters, the present day. And Mirkin, who I had appealed to for answers, or at least a narrative, before, seemed to be leaving us to our own devices.

We were, I think, trying to solve for capitalism. Mirkin, I believe, was also just trying to get us to consider capitalism objectively, to see its mechanisms clearly. It was almost like he was saying, But is it really that bad? Why?

I did not only catch Mirkin crying at the end of Modern Times. When we joined his class for another movie, the 1940s adaptation of The Fountainhead, I heard those same implacable sobs during Gary Cooper's courtroom speech. What kind of person can cry at Charlie Chaplin and Ayn Rand?

There was an odd intimacy to hearing a teacher cry. Sometimes I wish that I had asked him something about it. But what could he have said? There are moments I've feared he was not crying at all, but that he was having some kind of attack, and that we bear responsibility, that the other students and I were caught in some sort of horrific bystander effect.

At one point, the graduate student announced to us that when he graduated at the end of the semester, he would be fleeing to India. He had been living on student loans all this time, and he did not have (and did not intend to find) the money to pay them back. Another time we were sitting on the hallway carpet waiting for Mirkin to come strolling up, bike helmet in hand, and unlock his office door. The grad student had been reading Nietzsche, and he was summarizing an idea for me: “First you are the camel, and you carry all the knowledge you get from your teachers. Then you are the lion, and you tear it up. Then you are God, and you remake the world in your image. I feel like I'm just learning about all this for the first time, and I am light-years behind.”

∞ ∞ ∞

I came to know Harris Mirkin in his forty-seventh year at our small Midwestern commuter school. He had grown up in Brooklyn, gone to Hobart, and, in his words, drifted into graduate school at Princeton. Then, Kennedy started the Peace Corps. “Here, when you're 22, 23, you're still sort of a kid,” he told me. “In Ethiopia, I was an adult already.” As an underclassman, I claimed his path. In French class—the only place in college I can remember being asked this sort of thing—the teacher would say, Que vous allez faire aprés université? In a mediocre accent, I would respond, Je vais entrer les Peace Corps. But now they say the Peace Corps is just an extension of U.S. capitalism, a leftover instrument of the Cold War.

Mirkin found travel important, essential. A couple years after his class I was considering a semester in London, weighing the expense and the student loans. "Sell your soul to go," he wrote in an email. But I decided against it.

When my mother was his student, he directed an adult education course on the weekends. He brought in a variety of lecturers. One came to talk about communism. “Never been tried, never been tried,” the visitor protested. He portrayed the struggles of the bent-back people. “Their backs were bent because their labor was hard.” Hunched, he pantomimed shoveling. A dark patch on the front of his shirt grew mysteriously. With shock, my mother realized it was sweat. The teacher himself was laboring through his lecture on the history of labor.

Funny how in my mom's anecdote Mirkin is only a side-character, an observer who has brought to class a performer—a politically-radical mime.

After my third or fourth class, I was hanging around in the hallway with Mirkin. With a glint of recognition in his eye, he said, “Oh! You're Peg's son.”

∞ ∞ ∞

At the end of the spring, when Mirkin gave me the assignment for my final paper, my ears actually started ringing. It was late in the semester, the thirteenth or fourteenth week. “Just write me a book report,” said Mirkin. “Maybe twelve or thirteen pages.” I was reading a book called Where the Wasteland Ends. I hadn't even read The Waste Land.

When I remember that moment, I am looking at Mirkin from below and to the side of his paper-covered desk, as though I am falling out of my chair—an Orson Welles angle, Mirkin's bookshelves towering. It was no rational response. But I found ways to rationalize it. I have a girlfriend, I said to myself. I am in four other classes. (That's a lot!) I thought we were having fun. This sudden switch, from court jester to task giver, left me feeling betrayed. I was not expecting to write a paper.

I went to my mother's bedroom for advice. She was in the first phase of her treatment, going to radiation once a week then. It was not the sort of treatment where she slept all day or looked like she was dying. Her stomach ached. She stayed in bed and watched old movies, as she had done even before cancer. I'm not sure how much I took note of any of it.

She was the one who suggested taking an incomplete. She had taken one or two in college. She said her old friend from the writing lab—my sometimes-writing tutor, and the adopter of one of our one-too-many cats—had taken several incompletes in graduate school. He'd had a sign on his desk with another epigraph-worthy quote, Good writing is never finished; it is only abandoned. His incompletes all ended at the furthest extent of their deadlines, the last weeks before graduation. But I would not do such a thing.

I called Mirkin at his office, pled my mother's cancer. He said to try to get the incomplete done in a couple of weeks.

On the last day of the semester, I saw the graduate student in the school library. Mirkin had asked him, on the same day that my ears started ringing, for a term paper of thirty pages. I asked the grad student how it was going, and he told me he had started that day. “I'm just going to get it all out in one big go,” he said. Within the year, he was on the other side of the globe.

∞ ∞ ∞

One of the rare times our university made national news was thanks to Dr. Mirkin. He had published something the Missouri Legislature found so distasteful, they voted to remove funding from our school in the amount of his salary. Our school kept him on. The New York Times quotes him as saying, “The article was meant to be subversive.”

I subverted Mirkin's plan. I did not finish the incomplete in a few weeks. I knew I had the year. In the Chinese restaurant near campus—the one where I'd met my old classmate—I avoided him. I was sitting in the window. He was outside, getting on his bike. When I saw him, I ducked my head and hoped he would not see, sinking low as I could into the booth.

I enrolled to take another course with him in the fall. I had a plan. On the first day, I would apologize to Mirkin for not finishing the paper and would promise to have it soon. In his class, I thought, I would have the reinforcement I needed to get it done.

But when I went to the university bookstore, there were no books for his class. And when I looked at the enrollment website, the course was gone. There was no explanation.

A few weeks later our next-door neighbor, a math professor with an office down the hall from him, told us that Dr. Mirkin had been diagnosed with cancer.

My mom helped me write an email, extending my care.

In his reply, he wrote that he had a brain tumor. (Tum-ah, he would've said.) He wrote that his treatments would not be severe: “I won't turn mean or into a carrot.” In a post-script, punctuated with a winking face, he said, “Don't you still owe me a paper?”

Over Christmas break, I visited my girlfriend and her family. I brought the book and a number of articles on it with me. I can still picture one—a review from its release with an illustration of the author in jeans and a denim shirt—and where it sat on the corner of the coffee table through the length of my visit.

Where the Wasteland Ends lay on my bookshelf, loomed over my bed and leaned into my dreams. I worked on the essay in fearful fits, and then I would drop it again. It had to do with nature, and some kind of radical, spiritual counter to capitalism. It was very '70s. I didn't quite get it, but I thought there was something there. I felt it verbalized frustrations that I had only vaguely intuited. Like the way the grocery store shelves were lined with food products from which all nutritional value had been removed, while people were going hungry around the world. Its claims were utopian. Things could be changed. Nature, and reverence for her (as the author phrased it), were key.

Before the incomplete, I tried to explain to Mirkin. We were in the book-strewn office.

“It's so gushy,” I said. “It's hard to stand behind.”

“That's okay,” he said, bobbling his head. “We're allowed to talk about what's gushy sometimes, too.”

“I've had some dreamy moments just walking in the park,” he offered.

I ran into him early the next year. I remember being somewhat shocked by his appearance. His hair, the two white shocks falling to each side of his head, was all but gone. Freckles and age spots were visible on the top of his head, and when he moved his eyes, I could see the wrinkles of his brow move correspondingly. There were only two white wisps above each of his ears, which seemed as if they were about to fly off to the heavens, like curling clouds of steam from a radiator pipe. He wore a drab sweater the color of earth which hung limp off of his body.

He smiled in the same crooked way and spoke in his unfaltering accent.

"Yeah, I can still get around," he said. I noticed he was no longer carrying his blue bike helmet with the little mirror.

"Don't you still owe me a paper?"

∞ ∞ ∞

Modern Times is a film about people being squashed, metaphorically and literally, in capitalism's gears. Nature is posed as a comforting, tamed opposite (in the Tramp's daydreams), as desolation (surrounding the empty, stretching highway), and as the unknown (misty hills).

Combined, the sharp edges of nature and capitalism can make a potent force.

When my fair-skinned mother was tending her desert wildflowers in Paso, eventually the sun got to her. She got a small bit of non-aggressive cancer on her nose. In some way that I did not quite understand as a child, the doctors there did not treat it properly, and when we came to Kansas City she had to have a more extensive surgery that involved skin and cartilage grafts. I remember her coming home from the surgery, accompanied by the old friend who had taken too many incompletes. She wore sunglasses, and the sides and back of her head were wrapped in gauze.

Her skin still shows the mark—a small pock on the outside of her left nostril, like the impact crater of a tiny asteroid. The cancer marked her medical record as well. Now the possessor of a pre-existing condition, she was left uninsured. This meant that when she did get the cancer that endangered her life, she was unprotected from the accumulating medical bills. Without the debt, I imagine they might have fixed up and sold the too-old and too-expensive house my dad chose when we moved back to the once-middle-class neighborhood he grew up in. I imagine them downsizing, even leaving Kansas City for someplace with an ocean or culture, as my mom likes to put it. I imagine they would travel more.

∞ ∞ ∞

Potential Epigraphs:

The way of life is wonderful; it is by abandonment.

Ralph Waldo Emerson

Objects moving through spacetime follow curved paths around the distortions caused by the presence

of matter.

John Gribbin

Every deadline simulates the final event.

Anonymous College Student

∞ ∞ ∞

I wrote and emailed the paper to Mirkin a few days before the final deadline, a full year after I'd been given the incomplete. It was no incredible feat. The results were mediocre, turn-in-able. When I got no response, I called the secretary of the poly-sci department. She told me gently that Dr. Mirkin had become too ill to work. Somehow we got his home phone number. My mom thinks we used the phone book, the white pages. After a day of hesitation, I called and spoke to his wife.

I asked if I could see him. I was surprised that she said yes. She said he was being moved to hospice on Friday, and it would be best if I came after—sometime that weekend.

He died in the early hours of Thursday. I think of him, half-shrugging—Why stop moving now?

I got the news that the professor who'd taught me Marx and the meaning of alienated labor had died while I was working at the soap factory. It was a hip place—the catalog pages showed smiling factory workers dressed in funky thrift store clothes. We made all-natural goat's milk soap and other smelly products to be marketed towards the enlightened and affluent. We cashed in on the good juju of the '70s. My job was to put labels on hand soaps, bath salts, all-natural surface cleaners, candles, aromatherapy sprays. I could do 90 spray bottles in less than 18 minutes. I put in earbuds, drowning out the screamo a coworker blasted over big stereo speakers with NPR reports on U.S. drone strikes, or the sneers of Bob Dylan, I ain't gonna work on Maggie's farm no more.

That day, I was putting the caps on mini sprays—a process which involved arranging the tiny bottles (no longer or wider than a finger) in a wooden template, fitting a cap inside of each bottle, and placing over each cap a plastic socket with a rubber head, which I would smack with a mallet to click the cap into place. It was frustrating and frequently messy. The little lipstick-tube-sized bottles of yellowish liquid would pile up on the table, and like the Little Tramp tightening bolts on some machine part flying past on a factory conveyor belt, I would get behind. A bad smack of the mallet, and I spilled them all.

I took the call from his department secretary in the empty lunchroom. The walls were orange and green and bright purple. Mounted high up was a plastic marlin, gawking at me.

I decided to stay at work.

For about a week I had an F. Then, the paper moved on to another teacher and the F became an A. I made an appointment to visit this other professor. Maybe she had something to say. Her office was gray and tidy. No crazed heap of papers on the desk. Shelves in neat rows. She told me she'd read five pages and known that the essay was A material. She had stopped reading there.

I passed Mirkin's office on the way out. The poster of the upside-down atlas was gone. I looked in the little window. No piles of papers on the desk, no books on the shelves.

When it was time to return the book to the school library, I bought them another copy. I could not part with mine, full of pencil scrawl and little strips of Post-Its spilling from the pages in a multicolored snarl. A billion little tongues, blowing raspberries.

The night we got the news, my mom and I went walking in Loose Park. It was late, a cool evening with moisture hanging in the air. It was the beginning of summer. We walked under the trees in the dark. We could hear the tree frogs but could not see them. One called brightly right above our heads. We followed the loudest chorus across the street to a house with a massive yard and a gazebo all lit up. We stood at the edge of a row of hedges, awestruck by the sound. Hundreds or thousands of frog voices raised in cacophony. They were squatters on the property of the big house, crying, Alive, alive! We were mesmerized.

My mother was full of joy that night. She was healthy, on the other side of cancer.

“You know what we did tonight?” she said. It was two or three in the morning. We were sitting at the kitchen table. “We held a wake for Harris.”

After a pause, she added, “He would have loved it.”

∞ ∞ ∞

Why didn't I just write the paper? Maybe I left it incomplete to try to prolong the inevitable. I thought my life could continue to orbit his if I never finished the work. Maybe that's just a cute way to explain away my laziness. I think I wanted to write something that felt deserving of our time together. Finding myself not up to the task, I delayed.

For a long time I followed grief's laws of motion, made Mirkin's death a gravitational hinge. I found the photos from his memorial service online, and I saved them to my hard-drive. I felt there was something about his loss that defined me, and the reply to one of my many apologetic emails poked at me, taunting: “It's okay to live with a little guilt.”

I took two more incompletes while in school. I took the full year to complete each—putting them off until the last weeks and days. After each, I swore I would never take another incomplete. A year after my degree, I drifted into graduate courses. This time I was spending my own savings, not scholarship money. Halfway into the semester I started withdrawing from classes. I'd fallen in love. Two years before we met, she'd lived in Chile—had done a semester abroad and then moved down there. I was going to travel with her to Valparaíso, and then we'd move to the Blue Ridge Mountains. (It was like a song!) My teacher urged me to take an incomplete. I stuck to my convictions. I made my clean break with academia.

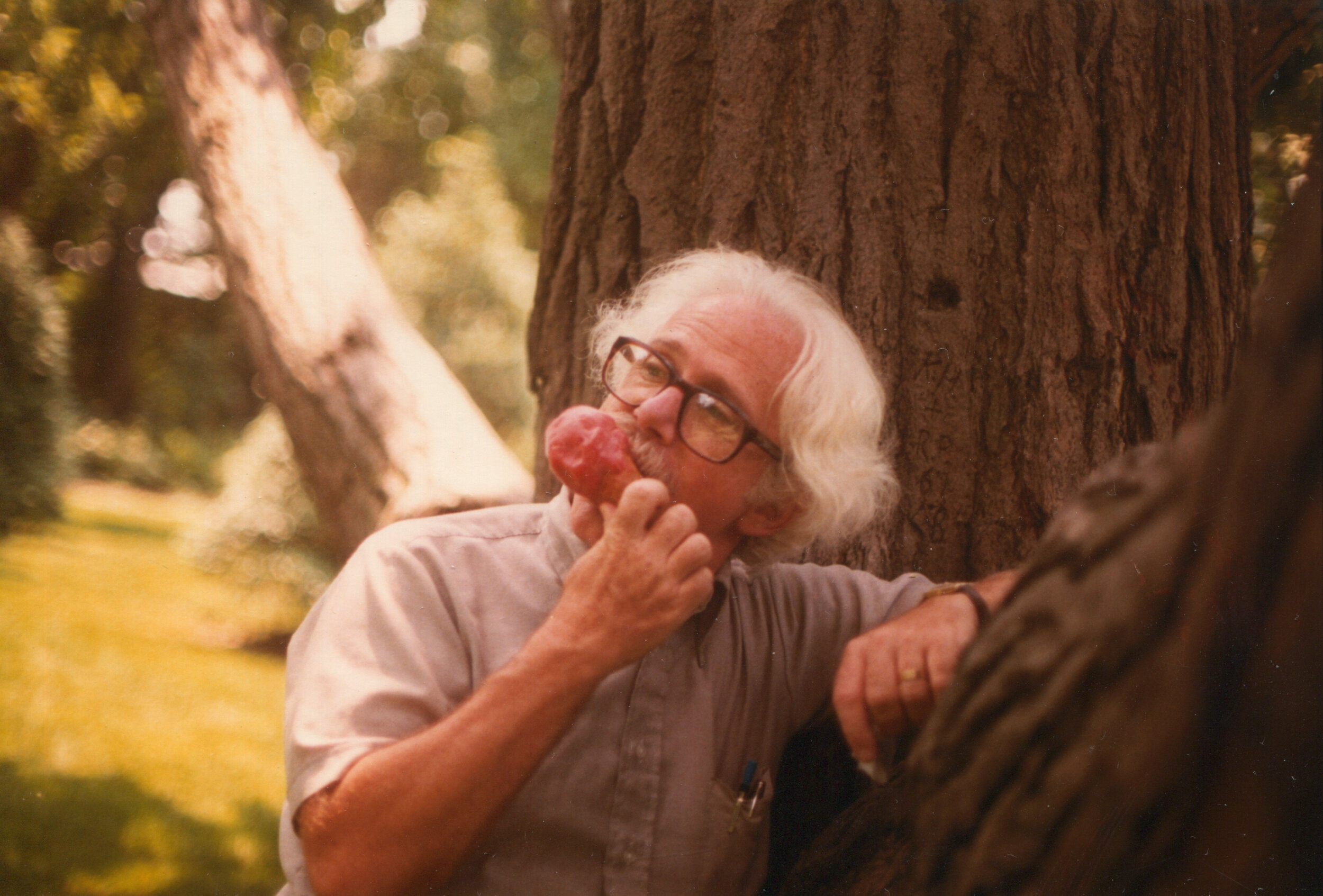

In one of the photos I saved, Mirkin is young. The only discernible difference in his appearance is fewer wrinkles. He has the same white hair, the same white mustache. His glasses frames are black and thick, like Buddy Holly's. He is in a park, leaning on a tree, biting into a turkey leg. I love this photo because I think he looks young and old, ever the subversive jesting professor, destined to fill that role. It is the Mirkin I know.

In another he is holding his grandson, smiling. In this photo, though it is Mirkin at the time I knew him, I see someone else. It is a family moment, and I feel I may be intruding. Inside me is a sense of my own oddness, my speck-like place in Harris Mirkin's life. While I was feeling guilty and avoiding him, there he was, living life.

After his death, one night I dreamed that I was standing in a long line at a wake in a big cathedral. In my hands, I held an ornately carved wooden box. I dared not open it, because I felt something menacing lurking inside nor could I give it away to anyone else.

∞ ∞ ∞

The morning I opened the Einstein biography, I remembered how accustomed to Harris Mirkin's presence I had once been. There was a time he had not been lost and irretrievable as the past, but ordinary. Never normal—he was too odd. His presence was routine, comforting. College stretched on forever. He was part and parcel of the seemingly endless cycle of my own days.

Mom's bought several books on Chaplin. She's read his autobiography, knows of the impoverished childhood, his mother's mental breakdown, and his exile from the U.S., where he made his fame. A victim of McCarthyism, he was kicked out for being a communist. Dad says he's reading the biography of Einstein but rarely has the time. For a couple weeks he shares facts about Einstein's schooling, his relationship with his teachers, his independence as a student.

All of these things go together somehow. Einstein, too, wrote of the grave evils of capitalism. They even met once, Einstein and Chaplin. A crowd gathered to applaud them. It was the silent film actor whose remark was recorded by history: “They're cheering us both. You because nobody understands you. Me because everybody understands me.”

∞ ∞ ∞

From a journal one year after Mirkin's death: I think my mom feels a certain pity for me, that I've decided to spend my summer in my room, thinking about Nat King Cole's version of “Smile.” I try to disguise the abjectness (inconsolability) of it. “Does this landscape look familiar,” I say, showing her the final scene from Modern Times. She knows why I'm watching it. “It's Paso Robles,” she says. Once, in her garden, a neighbor boy caught a small green frog in his hand. I tell her that it's not far, a few hours away. I don't tell her, but I'm excited to find that it's only a few hours from where the photo of Einstein on the bicycle was taken, and only a few years after. I can poeticize these things, I think. They make a triangle, a constellation. Constellations: a way of remembering people. Summer: the dog days, the dog star. We name our seasons by the constellations.

∞ ∞ ∞

At the end of the summer of Mirkin's death, in the dog days, my mother was hospitalized again. I was biking then—to school, to work, to the hospital, following Mirkin's precepts: “You go ten blocks one day. Ten more the next. Ten more the third. Soon, you can get your groceries.” Once I went from the soap factory to the hospital, and the fragrance that clung to me made her wretch.

She had an adhesion—a binding together of scar tissue left behind from the surgery to remove her tumor. Everything she ate, she threw up. She could pass nothing through, could digest nothing. In the hospital, a steady brown drip of stomach fluid fell into a bag hanging beside her IV. It ran from a hose that either went up her nose, or into her mouth. (A detail that, maybe, I have intentionally forgotten.)

It was only after yet another surgery, after that tube was gone, and she was sleeping peacefully if uncomfortably in the hospital bed, that I realized we had narrowly avoided catastrophe. In the following days, under the morphine drip, she stood before the big window looking onto gray clouds and rooftop with her arms spread wide, and said, “This is my sky.” She told a missionary who had stumbled into the wrong room, “I go to church in Loose Park.” I went to see the sweeping away of a sand mandala—a bright geometry of reds, blues, greens, and yellows that, in its destruction, became a spiral galaxy, a Van Gogh smudge swirling around a gravitational center. A monk in saffron robes said it was a mandala of the medicine Buddha. I brought the little plastic bag of sand to her hospital room. My father went home to shower, to sleep for the first time in days. Quietly, I fingered a guitar and watched her sleep.

∞ ∞ ∞

It was the summer before I started school, before I met Mirkin, and before Mom got diagnosed, that the cat died.

The tumor, the vet said, was close to the size of a child's fist. He could not pass anything through. Everything he ate, he threw up. If we resuscitated him, she said, he would eventually starve.

It was hot outside, but the operating room of the vet's office was being pumped with AC. We all stood with our hands on the furry body resting on the cold metal slab. There was no gore. The vet had sewn him back up. He was on his side, legs and paws turned inward toward each other, fetus-like. My little sister was there, my father, my mother. We each had a hand on him. Mine rested on a silky haunch. My sister was sobbing. Through tears my mother said, “He's still breathing,” her hand on the cat's chest. My father, the only one who goes to church, said a prayer at her request.

Later, my dad dug the hole. My mother brought the body into bed with her, and she and my sister sat petting him and crying, until he became stiff. I walked to the grocery store to buy them chocolate. I talked for a second to the cute girl who rang me up. Somehow, I felt not like such a loser as I usually did talking to a girl, like I had a place in the universe, or a leg to stand on, because there was grief in my heart that I was not letting out.

Dylan McGonigle is an MFA candidate at the Nonfiction Writing Program in Iowa City, where he teaches and writes (and occasionally plays his guitar). "The Incomplete " is his first publication.

Photo Courtesy of Kathleen Finegan.