Before moving back to Miami after seven years away, my husband and I lived together in Miami Beach, Chicago, Nashville, and Seugast, a tiny hamlet in Germany. Sometimes we had roommates. Sometimes we had a yard for the dog. In Germany, our house was surrounded by forests and fields, but the dog was back in the States. Our first house in Nashville had two bedrooms; in order to access one, you had to walk through the other. The second room was an addition, poorly executed. It had no insulation and was at least ten degrees colder than the rest of the house in the winter. Eventually, we stopped using it, except for storage. When my sister came to live with us in that house, we put her bed in the dining room and hung a curtain. The bathroom was so small, you could sit on the toilet and rest your chin on the sink at the same time.

Our second apartment in Chicago was a studio. It was in the basement, and had two large windows, one on each end of the room. But the windows faced north and south, so the room was perpetually dark. Because it was in the basement, our windows looked out onto people’s feet passing in the courtyard. We never saw our neighbors’ faces. Because the apartment was in the basement, the building’s pipes ran the length of the ceiling. The plumbing was bad. One day my husband came home to find me standing over the toilet, yelling, as the water spilled out of the bowl. The water was not clean. The apartment backed up onto a parking lot for businesses. The lot was used for the businesses’ dumpsters. We had a door off our kitchen that let out onto a porch, if a porch is what you would call it. My husband sat there in the afternoons and evenings, smoking, and picking at his guitar. He often left the door open. The latch didn’t hold very well. At night, you could see the rats from the dumpsters crossing the lot, small shadows.

One morning, after I’d left my husband at work, I came back home with the dog. I opened the door and heard a skittering in the kitchen. The dog rushed in growling. I’d grown up in Florida, where cockroaches the size of my index finger are common. They moved silently, though.

I used a flashlight to search the apartment. I shone the beam in the space between the wall and the refrigerator, and what I first took to be a large clump of dust and hair turned toward the beam of light and looked at me.

The super came and the dog and I stood on the porch listening to the super crash through our room. He called from the doorway to say the rat was dead, but I never saw him carry out the body. When I went back in later, I thought I knew what it felt like to have my home broken into. Only I’d never heard of a thief that left it’s shit all over the floor, in the bed, little sacraments of excrement around the base of the toilet.

***

My husband is at the kitchen table studying calculus. That looks interesting, I say, glancing over his shoulder at the heading in his textbook Geometry of Space. It is, he says. He launches into an explanation of the equation he’s working on. He’s excited and waves his hands in the air. He stands and uses a dry-erase marker to scribble on the glass door leading out to the yard. I try hard to follow what he says. It has been over a decade since I last took a math class.

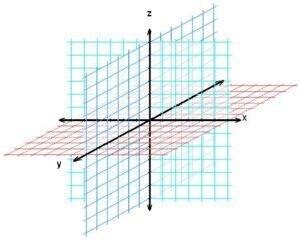

Later, I flip through the textbook myself. To locate a point in space (three dimensions) we need three numbers. We represent any point in space by an ordered triple (a,b,c) of real numbers. To represent the points in space, first choose a fixed point O (origin) and three directed lines through O perpendicular to one another, called coordinate axes ( x-, y-, z-axis ).

My husband tells me the point of origin can be any arbitrary point. It can be this, he says, pointing to an empty soda can on the table.

It could be you or me? I ask.

Sure, he says. You or I could be the center point of origin.

***

The first night out with the man who will become my husband, we agree to meet at a bar. We sit side by side. It is the first of many nights we spend like this. I ask him to tell me his life story, so he says he was born in Miami, but raised in Minnesota. Oh, I say. No wonder you don’t have an accent. Right, he says. Then he says his family moved to Santa Fe, which seems strange to me, but I have no reason not to believe him. When he tells me his family lived in Portugal next, I shake my head. You’re full of it, I say. He shrugs. Maybe.

Later, I’ll learn that Bob Dylan did this sort of thing—this reinvention of himself. Later— soon—I’ll learn that the man who will become my husband is, just then, trying to become like Bob Dylan.

We will sit in the stairwell of his apartment building smoking Marlboro Virginia Blends. He will pick at a poorly tuned guitar, will play me songs he’s written. They are no different from Dylan, except the lyrics are changed. His voice has the same quality, like sand against glass. But sand and glass are nice words alone, so we fool ourselves into believing they go well together. Later I will learn he makes his voice this way on purpose. My husband, and Dylan, too. People say Bob Dylan can’t sing, but if you’ve ever heard his first album, or Nashville Skyline, you know that’s not true. My husband’s family says he cannot sing. But if you’ve ever heard him sing a song about the father who’s not there, you know that’s not true either.

Around this time, I’ll pay special attention to the moon. I will remember it, full, and sitting on my husband’s shoulder, just outside the passenger window. Around this time, it will linger like a shadow. Later, when we’re living in Germany, we will go months without seeing it at all.

***

The shape of the universe is determined by comparing its critical density to its actual density. Based on this comparison, there are three competing ideas about the possible shape of the universe.

The universe is curved like a saddle. This is called an open universe. If this is its shape, the universe will expand forever.

The universe is spherical. It will eventually contract. It is closed and finite, though it has no end.

The universe is flat. Its expansion will slow over an infinite amount of time. It is infinite in size.

***

My husband and I came back home from Germany to Miami with our daughter a year ago. I didn’t know it then, but I was pregnant with our second child. We moved in with my parents to save money.

My parents’ house is large enough: five rooms, a formal living room and dining room, as well as a family room. But our life is squeezed into only a few hundred square feet. Our daughter’s bedroom doubles as the guest room. When family comes to stay, she sleeps in bed with us. Even without guests, she finds her way into our bed most nights. When she is not there, I think of her across the house. I think of her in the wide open space of her bed, and I fear that she is lonely. In bed with us, we are all allowed only enough space to fit the width of our bodies. In the mornings, I find her curled along the plane of my husband’s leg, her feet in his face, her hands under her chin.

Our second child, another girl, has a portable crib in our room. She wakes often. Some nights I am too tired to sit up with her, so I carry her into our bed as well. Every inch of mattress is used up. All the covers are on my husband’s side of the bed. I use my infant daughter for warmth, her small hot head against my chest, her warm mouth at my breast.

Most mornings, my baby daughter wakes before everyone else. I carry her into the formal living room, lay down on the couch in the dark, balance her on my chest. It is the only time the room gets used, I think, these early hours of the morning.

When it is just my husband and me in bed together, our bodies are two parallel lines. Once upon a time, we lay perpendicular, knees intersecting thighs, palms like coordinates along the clavicle.

***

When my husband and I first started living together, it was in a studio apartment near the beach. Maybe I imagined it, but the whole room smelled like salt. In the afternoons, the apartment grew hot; one side faced to the west.

We lived a few blocks from the water. We went to the beach to swim in the ocean maybe twice, but most days I would run along the marina, past the port’s entrance and onto the sand. Early evening was the best time to run. Not so hot, and not so many people.

I ran north toward Fifth, the high rises to my left, the wide open space of sand and ocean to my right. I listened to music through earphones—the same songs over and over—and I could not hear the water. Could hardly hear my own breath.

The apartment my husband and I shared had one of those miniature refrigerators. I guess the landlord thought the space would never be used by more than one person at a time, that a small, cold box was enough. The fridge had the kind of freezer that is just a little shelf filled with ice. Every once in a while, my husband or I would have to break the ice up with a knife to fit anything inside. The only thing we kept inside was a bottle of vodka, which we replaced every couple of days. My husband doesn’t drink anymore, not since just before our second child was born.

***

Here are the shapes bodies can make:

A triangle. A square. A rectangle. Parallelogram. Rhombus.

When I carried my daughters inside me, my body was a sphere. My body was the universe, closed and infinite, but with no end.

***

Our first house in Chicago was on Seminary, a few blocks north of DePaul and the Fullerton red line stop. We could hear the El as a distant rumbling from our bedroom. We lived on the second floor of the house, which looked alright from the outside, but was really quite shabby. The front staircase leading to our door was old and felt precarious going up. The stairwell was dark. I’m not sure we ever found the lights. The steps creaked under us and seemed like they would give way any day, so we used the back staircase instead, which was external to the house and led to a new, wood deck that we hardly ever used. The door off the deck led into the kitchen. The linoleum in the kitchen was coming up, and I think one of the cabinet doors fell off before we left that house. But the kitchen had a dishwasher and that was nice. The first bedroom was off the kitchen to the left. For some reason, that bedroom had two doors, one of which we kept shut. The room was long and narrow. Next to it was the second bedroom, which was half the size of the first, so small it could only fit a full-size mattress and nothing else. Because we were two and our roommate was one, we gave her the smaller bedroom, and she hardly ever left it except to shower and go to work. Across the hall from our bedrooms was the bathroom. Next to that was what I suppose could have been a dining room, except it had a pool table in the middle, which had been left there by a previous tenant. Because it was so cumbersome to move, the landlord had left it as well. We used it as a dinner table sometimes, so in the end, I guess that room was the dining room. Next to it was the living room. The only furniture in there was an old china cabinet, also left by a previous tenant, two bean bag chairs, a coffee table, and the television. The living room had two good-sized windows which looked onto the street. Across the street was a church, and we joked that our neighbor was Jesus. Our other neighbor was a bar, about four buildings down on the corner, frequented mostly by DePaul students probably. We only went there once or twice. There were many other bars in our neighborhood, and probably thousands more in the city. Around the corner from the house was Jonquil Park, which, in the spring, was filled with college girls in bikinis, laid out on beach towels or blankets, trying to get whatever sun they could. We would only stay in that house for three months.

***

Because many people have some difficulty visualizing diagrams of three-dimensional figures, you may find it helpful to do the following. Look at any bottom corner of a room and call the corner the origin. The wall on your left is in the xz-plane., the wall on your right is in the yz-plane, and the floor is in the xy-plane. The x-axis runs along the intersection of the floor and the left wall. The y-axis runs along the intersection of the floor and the right wall. The z-axis runs up from the floor toward the ceiling along the intersection of two walls. You are situated in the first octant, and you can now imagine seven other rooms situated in the other seven octants (three on the same floor and four on the floor below), all connected by the common corner point O.

***

The day we moved into our first place in Chicago, there was no electricity. It had been shut off weeks—maybe months—before, because the last tenant hadn’t paid any of his bills and then had taken off to California or Florida or somewhere. We’d learned all this about the old tenant before we’d even left Miami, but we didn’t know about the electricity until we were about eight hours outside of Chicago. The handyman had stopped at the house to leave the key for us, and then called to tell me. The electric company said it would take three to five business days to get someone out to turn it on.

It was the end of March. When we arrived in the city, daylight was already fading.

The man who would become my husband and I had driven since the early morning, from northern Florida, though we’d started in Miami the day before that, pulling a U-Haul trailer behind our car. If I’m remembering it right, the trailer was only about three-quarters full.

We pulled our mattress from the trailer and set it up on the floor of what would be our bedroom, then hooked the dog back to her leash and went looking for a liquor store and some place to buy flashlights. We were only a few blocks off Lincoln Avenue, and the three-way intersection of streets confounded us in a way that made crossing it that first time terrifying. We felt lucky to find a drugstore nearby, though we hadn’t noticed any liquor stores yet. I stood in the cold with the dog while my husband went inside for supplies. He came back out excited, a bag in each hand.

You can buy liquor in there, he said.

We went back to the house and put every blanket we owned on our mattress, drank half the bottle of whiskey, slept fully-clothed. We even left our coats on.

***

The man who will become my husband is trying to become like Jim Morrison. Maybe not as sullen. He looks good in leather pants. He drinks a lot, and after a night at the bar near our house, he lies down in the middle of the street. I’m not sure what the purpose of this is, but he yells at the sky while he does it. It is well past midnight.

***

I am thinking of wide open spaces. I am thinking of the way wind moves through an open field. I am trying not to be sentimental about this. I am trying, only, to remember. I am walking on the perimeter of this little German village. Maybe it is summer. Maybe it is only starting to be warm. From far off I hear the church bells chiming the quarter hour—which hour, I’m not sure. From far off I hear cars, trucks, tanks passing along the highway. The wheat in this field is still green. Pale, as though painted in by watercolor. The wind passes through and bends the stalks like a hand passing through a curtain of hair, like water rising and falling. I close my eyes and it’s water I hear. When I’m lonely like this—when I feel too far away from home—I picture myself near the ocean, even though my home is still miles away from the shore. Even when I’m home, I hardly make the trip to see the water.

When I was a child, my mother used to read a book to my sister and me. We called it The Lupine Lady, even though the book itself had a different title. In it, a young girl promises she will grow up to live by the sea. And she does. And she plants flowers. It is a nice story, but now that I think of it, it’s not a story at all. The girl becomes a woman, and, apart from one hard winter, and a bad back, never encounters any difficulties at all. Maybe it’s this story that taught me how to write non-stories, how to shape my characters so they move through life without problems. They fall in love. They travel from place to place. They wind up by the sea, or they don’t.

Rose Lopez is earning her MFA in creative writing from Florida International University. Her fiction has appeared in Big Muddy. She currently lives in Miami with her husband and two daughters.

Photo on Foter.com