We were stopped

at a red light, I was in the passenger seat,

and a guy crossing the street looked

at the Buick, then at us

Read More

We were stopped

at a red light, I was in the passenger seat,

and a guy crossing the street looked

at the Buick, then at us

Read More

Every night he dreams in infrared. Five, six weeks now, the world a thermal scan of itself. The map becomes the territory. A series of targets and the not-yet-threats in between.

Read MoreWinners and Finalists Announced for the 2014 Normal Prize in Nonfiction, Fiction, and Poetry

Nonfiction Winner: “Learning to Breathe,” by Jon Kerstetter

“The subject matter of "Learning to Breathe" is what initially pulls us with its heat, but what's more impressive about the essay is the way it circles back on itself and its terrible subject, its irresolvable difficulty, each time opening up to bring something else into its orbit: triage, breathing, how to consider the enemy, faith, responsibility, and focus. Yet at the center of all this gravity is the pair, binary stars, each turning around the other: am I a soldier-doctor or a doctor-soldier and how do I reconcile and negotiate the two? Read the essay.” – Ander Monson, Nonfiction Judge

Nonfiction Finalists:

“Interrogating Old Muskego,” by Jennifer Bowen Hicks

“Broken Sword,” by Matthew Gallant

Fiction Winner: “Our Mom and Pop Opium Den,” by John Jodzio

This was a really strong batch of finalists and though it was hard to choose, "Our Mom and Pop Opium Den," really stood out. The writing is so confident and clean and the story is witty, strange, and a little sad—a lovely combination. – Roxane Gay, Fiction Judge

Fiction Finalists:

“Storm Windows,” by Charles Haverty

“A Proper Bargain,” by Debka Colson

Poetry Winner: "Perennials," by Shelley Wong

Exquisitely crafted, underscored by an aching musicality, "Perennials" reminds us that regret and longing are elemental forces. Divided by oceans and silence from a beloved, the speaker's memory glitters with blossoms, arias, and fish sauce. In other words, with temporary pleasures, which remind us of the fleeting nature of all human relationships. This is a moving and startling poem. – Eduardo Corral, Poetry Judge

Poetry Finalists:

"Naubade," by Sam Sax

"Day of the Dead," by Jennifer Givhan

By Christina Hayes

Christina Hayes: Many of your short stories circumvent stereotypical perceptions of the South. What do you think about the recent phenomena of reality TV shows that seem to both exploit and exaggerate southern stereotypes (Duck Dynasty, Here Comes Honey Boo Boo, Redneck Millionaire)? How do you, as a writer, navigate these stereotypes in your work?

George Singleton: I was writing a whole novel based off the character Uncle Cush from the story, “Operation,” but then I saw some episodes of that show with the crazy uncle, and I realized he was a lot like Uncle Cush. I thought, damn, people are going to think I copied that dude. So I ditched the novel. (For what it’s worth, I wrote A&E last year and said I would never watch that show, nor buy products advertised in the time slot, because of the anti-everything comments from the one cast member.)

I’ve never seen the Honey Boo Boo show, or Redneck Millionaire. I’ve seen the ones about Louisiana swamps, and ax men, and mountain men. Listen, I would be willing to bet that a lot of writing done down here that never gets published in magazines has grandmas spitting snuff while rocking on the front porch, and so on. The South is diverse and complicated, let me tell you. There’s the Old South (“Wouldn’t it be great if we’d won the Civil War?!”) and the New South (“Hey, I can afford to join Augusta National now, seeing as I made all that money in textiles”). Nowadays, there’s the New New South—“I don’t play golf, but I could join Augusta National if I wanted, seeing as I invented a new way to process grits down at my low-country farm, which made me a billion dollars, that all those old codgers buy before embarking on a Civil War re-enactment.”

I try to have what seem to be stereotypical southern characters act in surprising and good-hearted ways, I suppose. Not so much that it’s beyond willful suspension of disbelief. I couldn’t pull off someone using racist terminology suddenly giving away his estate to the United Negro College Fund, I doubt. But I’ll probably try, sooner or later.

As for stereotypes, too—notice how zero of my characters, in any of my books, have used racist terminology. Goddamn. There are enough problems in the country without having characters spout off hurtful epithets twenty times per page.

CH: In Between Wrecks, most of your narrative voices are outsiders or have outsider perspectives within this rural southern culture. Why choose to have outsiders serve as narrators throughout these short stories?

GS: To be honest, I’ve never even considered it, though I guess in a way I consider myself somewhat of an outsider. Although I’ve lived in the South for 48 of my 55 years, I still feel as though I don’t fit in. I’ve never killed a deer. I read books. I don’t chew tobacco. I do like stock car racing, though. I’ve been known to drink bourbon.

Seriously, I guess most stories can be categorized as “a stranger comes to town” or “this character feels uncomfortable within the setting, for various reasons.” I guess I choose the latter, for better or worse.

CH: Your writing is often noted for its ability to find humor in pain, and Between Wrecks is no exception. Are there any particular writers you’d say influenced your interest in the grotesque?

GS: I believe in Samuel Beckett’s notion that there’s nothing funnier than human misery. And that idea goes all the way back to Aristotle: “My life might suck, but at least I didn’t kill my daddy, sleep with my mom, and finally stab my eyeballs out.” Flannery O’Connor said, “Whenever I’m asked why southern writers particularly have a penchant for writing about freaks, I say it is because we are still able to recognize one.” I think somewhere along the line she added that we not only notice them, but we put them up on pedestals.

CH: Do you think readers gain something from your close look at these “freaks?”

GS: I hate to even use the term "freaks." Not that I'm politically correct whatsoever, but everyone is a freak to a certain degree—it’s just difficult sometimes to comprehend the "inner freak" of obsession, et cetera. I think that's what I most likely hone in on with characters, both protagonists and antagonists—that they suffer from irreversible or irreparable obsessions. I'm hopeful that readers will commiserate with my characters' odd flaws.

CH: There's a lot of hidden bourbon in Between Wrecks. Each story has a character recovering a hidden bottle of bourbon from an obscure hiding spot. What’s the deal with all this bourbon? And why do people keep hiding it?

GS: It’s about one member of a relationship knowing what’s best for another member of a relationship, or about one member of a relationship knowing that his better-half’s killing himself unknowingly. Doesn’t everyone play this game? I’ve found my own bourbon in the washing machine, and I know I didn’t put it there.

Saturday night brings both pledges and lies of limitlessness, of a night never ending, a jukebox always playing, dance partners always spinning, car wheels revolving on roads that never end in daylight.

Read More

I contracted my own White Death back in graduate school, when I was first assigned Moby-Dick, and had to wake up at five or six a.m. to swim its immense dark waters.

Read More

I heard something other than

the chattering of birds in the trees,

something like the hint of music

When my husband returned from Afghanistan, we hoped our lives might go on much the same as before. Bill hadn’t been in much danger. We’d been married for ten years. We had the support of good friends and a large extended family. Our two little ones were healthy, and within a few months of his return, a third was on the way. It didn’t seem unreasonable.

Read More

By Stacey Balkun

Stacey Balkun: This entire collection traces a modern-day relationship between Arthur, Guinevere, and Lancelot. The Normal School was proud to publish two of these awesome poems, and we’re curious: How did this project come to be?

Shelley Puhak: An ongoing conversation with certain poems (of the Modernists). An ongoing war. A financial crash. Occupy Wall Street. The uncanny cycles of history. The many myths about waning empires. And one too many Can poetry matter? articles.

SB: What did you think about when ordering these poems? Did you face any organization issues when putting these poems together?

SP: Organizing the poems was more difficult, in many ways, than writing them! I had, at one time, four or five different versions I was deciding among. I had many possible options: organizing by seasons (summer, autumn) or elements (fire, wood, water, metal) or lingo (medical, technological, commercial, Arthurian).

Everything is in threes in this collection: the tercets in the poems, the individual sections featuring three poems each, 16 sets of 3. I became so obsessive about the threes that at one point I wanted to cut one section just for the sake of having the asymmetry of 15 sets of 3, but then I’d pull one poem out of one section, and then the whole house of cards collapsed and it was back to spreading the pages out on the hardwood floor.

SB: Several of these poems are written with variable foot, a metrical device William Carlos Williams “created” to resolve the conflict between form and freedom in verse. In a way, this collection works to resolve a conflict between form and freedom, the obscure and the obvious, mythology and truth. How do you see form functioning in this collection?

SP: Maybe form as a sort of webbing? One that connects the poem to the past and characters within the poems to one another.

Each of the characters has a favorite form: Lancelot always in couplets; Arthur in stricter, often rhyming, forms; Elaine in breathless enjambed asymmetrical strophes; and Guinevere in terse tercets. And the Speaker, as judge and jury, dabbles in all of those forms, trying on the voices of the various characters. Form serves to show connections (hopefully) between major and minor characters, too: between Betsy Patterson and Guinevere, for example, or the Great Fire of 1904 and Elaine.

In "Guinevere, Facing Forty in Baltimore, Writes to Lancelot” and “Guinevere, to Arthur, On Starting Over,” Ginny speaks in her usual style: the imperative____, the end-stopped lines, the

descending

staircase

tercets.

In “Arthur’s Grave,” the “I” has become a “we,” and so there is a blend of Lancelot and Guinevere’s voices: five quintets blending the staggered tercets and symmetrical couplets.

SB: “Guinevere, Dissecting Lancelot” appears in the Spring 2013 issue of The Normal School. This poem describes a physical dissection of a body. Guinevere recounts how she: “…carved out cross sections to sample [his] nerve…” and tosses “[his] slop in [her] stainless.” The images are so gruesome yet beautiful—we can’t look away. Tell us about this poem! Where did it come from? What does it do for the narrative of Guinevere in Baltimore?

SP: How this poem was classified in my own notes: summer metal medical.

This sexy autopsy takes place after a swim in the river, past the spring of the relationship and the kingdom, with Guinevere testing Lancelot’s “nerve” and wondering if she has the “stomach” to continue or the “eyes” to see where it is headed.

As for where it fits in the larger narrative: this poem is in conversation with the two other poems in this section. “The Court Physician Interviews Guinevere” is founded on the medicine of the Middle Ages and the belief that “we love with the liver.” “Lancelot, the Microbiology of Us,” locates love (and responsibility) in the fungus and bacteria that live within us. This poem locates love and pleasure in the nervous system. Why? We become our metaphors.

SB: Your first collection, Stalin in Aruba, was a sort of project book, too. What are you working on now?

SP: I’m actually working on a nonfiction project right now, tentatively titled Finding Eva, about the process of hunting down evidence of a great-great-aunt who committed infanticide in Austria-Hungary circa 1880.

Bonus Question: If Guinevere watched The Wire, who would her favorite character be?

SP: Omar!!!

By Jennifer Dean

Jennifer Dean: In the title poem, you write, “I am a poet retelling a telling.” So much of this collection is about the act of storytelling. Can you tell us the story of how you came to write this particular collection?

Andrew McFadyen-Ketchum: The first few poems I wrote in graduate school were terrible, and my workshop let me know it. This is the greatest gift a writer can receive: real, true, thoughtful criticism.

Judy Jordan, the workshop leader, always saved my horrific poems for last and proceeded to rip them apart, line by line, stanza by stanza, word by word…whatever was necessary. But when there was something good to say, when there was some encouragement to provide, she and the workshop did that, too. “We clearly have a good poet here,” Judy would say, “now if only we could get some actual poems out of him!”

The fourth poem I turned in was “Ghost Gear.” I don’t remember first writing it, but I do remember calling up my dad to read drafts to him. And I did a ton of research. I pulled up maps of the Aleutian Chain, depth charts, read up on the different types of nets they used and how they used them, downloaded schematics of the plane they landed on the beach. I even bought a model sockeye salmon who peered at me from my desk through its beady, plastic eyes.

As always, Judy waited until the end of workshop to slam “Ghost Gear,” but to my surprise, celebrated it. There was something in the way it told my father’s story while telling my own that struck a chord. While it was narrative, it was also highly musical. It didn’t tell the story; it sang the story. Judy and I came to call such poetry lyric-narratives, and she and the workshop demanded I write more like it. I could write a book of such tall tales told from that multifaceted perspective, the workshop said, so that’s what I did.

I completed the first draft of Ghost Gear in January 2008. The five “father-story” poems (“Ghost Gear,” “The Ever-Chamber,” “The Torchbearer,” “Lost Creek Cave,” and “First Catch”) serve as the backbone of the book. The lyric-narratives that branch from there make up the rest. I started submitting Ghost Gear to a short list of first book prizes in the spring of 2008. I revised it every time it got rejected and certainly would be doing so today if Arkansas hadn’t published it.

Why this book first? Because it’s the first one I wrote. Poetry is a collaboration with the world. I repeat: Poetry is a collaboration with the world. I didn’t write these poems; I discovered these poems. I have innumerous people, events, tragedies, successes, heartbreaks, victories and strikes of lightning to thank for it. I am eternally grateful.

JD: Your style has been compared to the styles of Elizabeth Bishop, Robert Penn Warren, and Rodney Jones, among others. These are poems in the tradition of the vertical narrative; they begin grounded in the particulars of a place and time –Shreveport, Louisiana, 1955, Balsam Mountain, North Carolina, Lost Creek Cave, Tennessee—and levitate from there, creating almost-Jungian associations that spiral upward and out. How much would you say you were influenced by writers like Bishop, if at all, and how critical was place and time in the crafting of these poems?

AMK: I think it’s reasonable to say Bishop and Penn Warren helped initiate the contemporary movement of which I am an avid student. I read, on average, three collections of contemporary poetry a week. In grad school, I read a book every single day, Monday through Friday (Lisa forced me to take the weekends off), for three years. But I rarely read poets who aren’t breathing oxygen. This is certainly a failing on my part, but, again, poetry is a collaboration with the world. No poem lacks a predecessor. When I read, say, Ross Gay, I’m also reading what he’s read. When I say Judy Jordan is an influence, I’m also claiming her influences. When I read a book by Paisley Rekdal…you get the idea.

I think you’re right: my poems tend to start in one place and “spiral upward and out” from there. My poems tend to be concrete even as they are rooted in the abstract. I’m not sure how much control I have over that versus how much that is the result of my influences, however direct/indirect they may be. Maybe it’s the result of a thorough exploration of my subject. Maybe something else.

It’s important to understand that I have very little control over the abstract/philosophical aspect of my work. I exert a ton of control of the “brick-and-mortar” of a poem (the line, narrative, musicality, etc…), but the more metaphysical part, the more philosophical, artistic side of this business is a total mystery. I consider myself an artist, but I have no idea what that means. I’ve been calling myself a poet for twenty years, but ask me to define the word itself, and I’m off babbling to myself about god and the multiverse in a corner of the room.

I was raised agnostic/atheist but have become more and more a believer over the years as a result of all of this. There’s a spiritual, ineffable aspect to this whole business I can only come close to touching via verse. People often ask me how I know a poem is “finished.” The first answer is, of course, “Never,” but the more utilitarian answers is, “Once I know what the fuck I’m doing.”

My process is simple: I start with a bunch of words and <i>no</i> idea what I’m doing. The less I know, the better. As I gain little nuggets of understanding via writing and revising, I gain a little traction. Once the poem has taught me how to write it, once I understand what the poem is, I’m steps away from completion. It’s the poetry, you see, that does the work, not me. It’s my influences, living or dead who write this stuff. It’s the time and place in which these poems were written that writes them. It’s the natural world. It’s all those little strikes of lightning. Hard work. Frustration. Joy. Not me.

JD: Your poems often pose questions like “what else can I say of these ball-peen hammers / of distant thunderheads?” or “why this life not a life without death’s clang / from time to time between the ears?” Questions appear to play a central role in the momentum of the poems in this collection. What would you say the role the question has in this collection?

AMK: I never thought of them as adding momentum, pushing the poem forward, but I think that’s exactly right. Questions are not just another mode of speech, they prompt further thought/investigation, they probe the reader and, in a poem’s case, the speaker into unknown territory. The first 1.5 lines of Ghost Gear (“What do I know of God but that each winter / I thank Him for it?”, “Singing”) ask a question and, in many ways, the rest of the book is an attempt to answer that question.

JD: You depict every character in Ghost Gear without malice or the suggestion of resentment, even in the case of the young boys in "Stormdraining" and your younger self—chasing your demons—in "Night Driving." Fiction writers often speak of loving their characters, even (and, perhaps, especially) the “bad” ones. Does this also apply to poetry?

AMK: I think we have to love our words and our characters. This is something I’m relearning on this book tour. Readings go really well when I love the words I’m reading, when I spit them out like little jewels, little beams of light. They don’t go so well if I’m questioning my words or don’t have the energy to express them with love.

If our characters are made up of words, then, yes, we must love them, too, no matter how bad they may be. Sam and Tim of “Stormdraining” aren’t racist; they are products of racism. And they were not loved. This held them back from living greater lives. I think it’s my duty to love them, even if they were cruel to me.

I am the son of my mother and father, but I could just as easily have been their daughter. I could have been aborted. I could be the child of warlords. I could have been born a thousand years ago. Thus malevolence… whatever form of non-love we feel for those around us strikes me as a little shortsighted, if not outright counter-productive.

Don’t get me wrong: we’re not just what/where we come from. We are what we do, the decisions we make. But lots of people don’t have choices. Many of us are forced into a corner and lashing out is our only option. It certainly happened to me when I was a kid and still happens. But, thankfully, I found poetry early on. I experienced the harsh world I grew up in from the point-of-view of an artist, a welder bringing together his materials, not just as bystander, actor, or victim.

This trait is what kept me away from the sort of hatred and malevolence I grew up around, and it’s the reason I write. My parents are activists. They raised me with the belief that I had to give back. It took me a long, long time to realize that’s what I do in a poem. “Stormdraining” gives back to Tim and Sam.

Andrew McFadyen-Ketchum is the author of Ghost Gear (University of Arkansas Press, 2014), editor of Apocalypse Now: Poems and Prose from the End of Days (Upper Rubber Boot Books, 2012), and series editor of the Floodgate Poetry Series: Three Chapbooks by Three Poets in a Single Volume (Upper Rubber Boot Books, 2014) and founder and managing editor of PoemoftheWeek.org.

Photo credits: www.andrewmk.com

Robert answers Normal questions about his most recent book Anatomy of Melancholy.

By Jennifer Dean

Jennifer Dean: In Anatomy of Melancholy, there is a strong sense of a speaker (or speakers) working through ideas. It seems that you approach each subject, each poem, with a question in mind that you're looking to answer in the poem. Was that the case with this collection?

Robert Wrigley: Answers are not common in poems, I don't think. That is, the best poems do not answer questions at all: they provoke questions. I don't seek answers, either as poet or as reader of poems. I'm far more interested in creating some sense of--call it heightened consideration. The world offers up a more or less constant stream of possibilities; the poet just makes (or attempts to make) something of what the world offers. James Dickey used to say the poet was "an intensified man" (he means human being, of course), and while that seems a little hubristic it's also true. Poets have to see very, very deeply. No vision for the poet, no vision for the reader.

Jennifer Dean: So what would you say you were looking at most while writing Anatomy of Melancholy?

Robert Wrigley: Well, this is going to sound V-A-S-T, but I suppose it's simply that thing we call the human condition. Which is joyful and anything but. Robert Burton, clearly, was what we call "depressed" or "depressive." He believed, as he said in his The Anatomy of Melancholy, that melancholy was the "condition of mortality." To be alive, a living human being, is fundamentally to know that you will die. That everyone you love will die. And yet, we go on. What else is there to do?

In my poem, Larkin says "I hate being dead," and who wouldn't (there's a reference to his poem "The Old Fools" in this poem, as well as the more obvious one, to "This Be the Verse")? I love the fact that we go on. I'm baffled by it too. But I do love it. We keep, for example, writing poems, and there's something enormously quixotic, even foolish, about that. As Dick Hugo used to say, be "foolish, but foolish like a trout." Meaning, I think, be alive.

Jennifer Dean: "Be foolish like a trout" in the sense that we occasionally swim against the current? (I am not a fisherwoman; I know salmon swim up-stream, but that's about it.)

Robert Wrigley: I'm a relentless fly fisher for trout. I catch them (which usually involves them being at least momentarily foolish and seizing a fake bug from the surface) then I admire them and let them go. I think the foolishness of the trout is just a sort of absolute ease within its own skin, something tremendously uncommon in human beings. Perhaps this is due to our abilities with language, with ideas and abstractions, with that sense that we not only might die but will die. But the trout, feeling hunger or desire, seeks what will deliver it from, or to, that desire.

Poems are that way for me. It's the lunatic difficulty of the art that addicts one to pursuing it. If it were easy, well, why would anyone do it? So, in a sense, writing poems at all is an essential foolishness. The key in that phrase, however, is the modifier. Essential. Once you're committed to making poems, you will continue to be foolish.

Jennifer Dean: As to Robert Burton's book, how much of a role did that particular work play in your writing? Your book and his deal with the same subject matter, but clearly the take-away message from each is different. Was that deliberate or just a product of your particular approach to poetry?

Robert Wrigley: I can only write my book, my poems. There wasn't much point in recapitulating Robert Burton, and I couldn't do it anyway. I think I probably value sadness and melancholy because they are a kind of affirmation of the condition of life. If you feel melancholy, it means you are feeling something, and feeling—I mean this in the physical, intellectual, and emotional senses--is a validation of consciousness. We know the stage will be littered with bodies at the end of Hamlet, but still we go to see the play. It will make us suffer beautifully, and that's just one of the beautiful things about literature, and the aspiration (also foolish) to make it. Burton may have hanged himself; it's unclear. It's rumor that is unsubstantiated. I think I'm an unlikely candidate for suicide. I also think writing is a way of staving off despair, of confronting mortality and mendacity and stupidity, and also of celebrating the fact of our feelings and experiences.

Jennifer Dean: A lot of people claim their major problem with poetry is that they don't understand what's going on. Your poems are meant to raise questions, but aren't unclear about what's happening or to whom. Is that one of your goals?

Robert Wrigley: It's hard to be clear, and it's especially hard to say what on earth "clear" might mean. Is Eliot clear? Absolutely, although what his clarity asserts is not the least bit reductive. People think they don't understand a poem when they can't reduce it to some sort of bromide, a kind of bumper-sticker length "theme." No, they understand poems, they just prefer a kind of narrow idea of understanding. The poem means what it says, but what it says is no more important than how it says it. So reading poetry is not something to be done in order to receive the information it contains.

Reading a poem is, or ought to be, a whole-body experience. What I look for in poems is delight, instruction, and wounding. Some poems do one of those things; some two; some all three. The ones that do all three are great poems. You might sit down to write hoping to do all three things to the reader, but sometimes you do just one. That's fine. But you should always aspire to do the impossible. A poem that can be paraphrased, or reduced to a theme, is dead on arrival.

Jennifer Dean: The expectations of the reader are a large part of the reading experience, though it isn't something that gets addressed directly in most literature classes. How do you advise your students to approach reading poetry?

Robert Wrigley: I usually tell them there is no reader. Or else there's an imaginary one, sort of the smartest person ever. Mostly what's required of the reader is receptiveness, a massive open-mindedness. Be available. Don't assume anything. Let the poem teach you how to read it; let the poet teach you how to read her poems. If the poem—or even the poet--doesn't work for you, so what? Can you imagine being the poet everyone loves? A fate worse than death.

As for expectations, they need to be done away with. The poem that matters is the one that surprises you, somehow. It may take you where you could not have imagined, or it may express something in a way you could never have thought it would. Same thing for the poet in the writing of the poem.

You know you're getting somewhere when you surprise yourself. But like everything else, there's no simply saying, "Okay, now I'm going to surprise myself." That'd be like saying, “Okay now I'm going to scare myself.” You write your way to surprise, you write your way to a destination you never knew existed, you say what you say in a way you never thought yourself capable of. In theory, that happens regularly. In practice, not so much. It's the journey. It's the process that matters.

Robert Wrigley teaches poetry at the University of Idaho along side his wife, fiction writer Kim Barnes. His collections of poetry include Earthly Meditations: New and Selected Poems (2006), Lives of the Animals (2003) winner of the Poets Prize, Reign of Snakes (1999) winner of the Kingsley Tufts Award, and In the Bank of Beautiful Sins (1995) winner of the San Francisco Poetry Center Book Award. He is the winner of five Pushcart Prizes, and a contributor to The Normal School.

By Stacey Balkun

Stacey Balkun: How did the story move from a zombie story to a historical novel?

Beth Ann Fennelly: A few years ago, Tommy was asked to contribute to an anthology of stories set in the Mississippi Delta. He agreed but the deadline was looming, and he was running out of juice, so he fished through his drawer of old busted drafts and reeled in a failed story. It was a zombie story that he’d written a few years prior, and he gave it to me to see if I had any ideas. I hate zombies, mainly because I think real humans are weird enough to do anything, so why displace all the anger and passion onto the undead? But the story had something going for it: two rangers were roaming across a zombie apocalypse, and they come across a baby and find someone to be its mother.

Tommy sent it to the editor of the anthology, Carolyn Haines, who was like, um, no thanks. This is awful. But if you set it in the MS Delta. . . She also suggested thinking about the flood of 1927 as a setting. I had been obsessed with the flood ever since moving to MS and hearing about it for the first time. Tommy asked me if I’d work on the story, and I did, and gave the story back, and he wrote some more and returned it to me. We did this a few more times until eventually we were finished and, without exactly meaning to, had co-written the darn thing. Set during the flood of the Mississippi River in 1927, “What His Hands Were Waiting For” is a story about two government agents riding through the flooded Delta. They come across two looters and shoot them, and then realize one was a woman and they’d just orphaned her child. So the agents take it with them and give the baby to a woman they come across whose own child has recently died. The end.

Or so we thought. That little story had some legs, and was reprinted in a few anthologies, one of which made it into the hands of Tommy’s agent, Nat Sobel, who called and said, “You never told me about this story.”

“What’s there to tell?” asked Tommy. “It was just a lark, a quick side project.”

“No, it’s not,” Nat said. “It’s your next novel. And you and Beth Ann are going to write it together.”

Which sounded crazy, and crazily irresistible. Because, although months had gone by, the characters, somehow, were still ghosting around our heads, chatting with each other. And the historical research was so rich that it almost felt frustrating not to do more with it—like opening a vein of gold in rock and pocketing just a nugget. And it was fun to collaborate. Writing can be lonely. Here we were, writing with our best friends.

We agreed to give it a go and promised to have a draft in one year. It took us almost four. (One of our first lessons about collaboration: a novel written by two people isn’t finished twice as fast). We focus on two people whose fates become tied to the flood. We alternate chapters between these two point-of-view characters, a female bootlegger and a male revenue agent, creating a novel that’s about 100,000 words. Ours is a story of a flood, but also a love story, and, bigger, the story of how individuals come together to form a family.

SB: What drew you to this particular flood instead of a more recent natural disaster?

BAF: The flood of the Mississippi River in 1927 destroyed 50,000 homes and was the greatest national disaster our country had ever seen. But when I moved to MS, at thirty, I’d never heard of it. How can this be? A region the size of New England was drowned. If it HAD been New England, the event would be in every history book. But the folks affected were mostly the disenfranchised, poor sharecroppers, black and white.

The literary world is often dominated by the coasts, but this great big Mississippi story begged to be told. We first discussed this after Katrina, which had so many similarities with the flood of 1927, including the fact that the government showed an appalling lack of concern for the affected Southerners. Writing about the flood of 1927 was in a way also writing about Katrina, I suppose.

SB: What are some of the challenges you encountered while writing a historical novel? How do they compare to the challenges involved in writing more modern fiction, nonfiction, or poetry?

BAF: The best part of writing a historical novel is research. That’s also the worst part. Because one can get a little addicted to it. Facing the blank page is scary, but when researching—especially using the internet—link leads on to link leads on to link. And there came a point when we realized that reading more wasn’t going to help us write the novel. Reading more was another word for procrastination.

SB: Could you talk about how the main characters developed, either on the page or in your minds? There are so many fully-realized people in this book: were there any real-life inspirations for Daisy, Ingersoll, or Jesse?

BAF: There’s a female point of view character who’s a bootlegger. The male point of view character is a revenue agent. So you can see the natural conflict. When we began the novel, I was purely writing from the female character’s point of view, while Tommy was writing from the male character’s point of view. It was actually going pretty slowly, partly because Tommy was out on book tour for his novel, <i>Crooked Letter, Crooked Letter</i>. We were making some headway but not a lot. It actually became a lot more fun and started going more smoothly when we started doing what we called dueling laptops. We wrote together in the same room, side by side, each on our own laptop. We’d start with the idea: okay we know we need this scene on the levee, and we know this person has to arrive on the scene, and this conversation has to take place. After a while we’d stop and read our parts to each other. Sometimes we’d take all of one person’s, sometimes we’d combine some, or do something different entirely from an idea one of us had gotten from the writing. When we started doing that, the writing became more fun and surprising things happened.

There weren’t any real-life inspirations for the main characters, though lots of bits and parts of people we know found their way into the book.

SB: I heard that a “Colin” dies in all of Tom’s books. Can you tell me more about the death of the Colin in this book?

BAF: Well, I guess that secret is out at last. Before I met Tommy—and we’re talking 19 years ago now—I had a Scottish boyfriend, whose name was Colin. I adored him but he dumped me, and not too long after I met Tommy and the rest is history (15 years of marriage and three kids!). In Tommy’s first book, he kills a character named Colin, and it became a kind of joke that in every book thereafter a guy named Colin would die, and usually in a cowardly or embarrassing way. So in this collaborative novel, we knew Colin would have to die. The funny thing is, due to the way we apportioned the chapters, the killing of Colin fell to me! So I polished him off this time. Poor Colin. He was actually quite a nice guy.

Beth Ann Fennelly teaches poetry and nonfiction writing at the University of Mississippi and is a contributing editor for The Normal School. Her first book of poetry, Open House, won the 2001 Kenyon Review Prize and the Great Lakes College Association New Writers Award, and was a Book Sense Top Ten Poetry Pick. It was reissued by W.W. Norton in 2009. Her second poetry collection, Tender Hooks, and her third, Unmentionables, were published by W.W. Norton in 2004 and 2008. She also published a book of nonfiction, Great with Child: Letters to a Young Mother (Norton), in 2006. The Tilted World, the novel she has co-written with her husband, Tom Franklin, was published by Morrow on October 1, 2013.

I left the bar humming bare traces, the final moments of the song like excavated bones, already fading in the daylight, in the archeology of my head.

Read More

then plaster falling and the billow of gypsum

after your sister blows a hole in the ceiling

of your brother’s bedroom with the shotgun

he left loaded and resting on his dresser.

My disobedient body pierces the I

Music drifting landward hand in hand

The cafés have a kind

of tea that is just

the temperature and taste

of air breathed in summer

Jamaal May is the author of Hum (Alice James Books, Nov 2013), two poetry chapbooks (The God Engine and The Whetting of Teeth), and the winner of the Beatrice Hawley Award. His poems have been published widely in journals such as The Believer, The New Republic, POETRY, Ploughshares, Kenyon Review, and New England Review. May's poem "Hum for the Stone" appeared in the Spring 2013 issue of The Normal School.

By Stacey Balkun

Stacey Balkun: I re-read Hum during and after the Zimmerman trial and couldn’t read “Man Matching Description” without thinking about Trayvon Martin. This is an important poem about false accusations. What can we do? What’s next? How does this poem (or your poetry, or anybody’s poetry) play a role in ending violence and injustice?

Jamaal May: That re-contextualization happened for me as well. A few people reposted the poem, as it was readily available on <i>Blackbird</i>’s website, shortly after the shooting occurred. What is terrifying about how well the poem fit the moment is how long ago it was written, how many times before that a similar poem was written, and how many such poems will be written in the future.

I’ve been thinking a lot about poetry being pretty much the only art form in which the practitioners are regularly called upon to explain if and how their art will solve society’s ills. I’ve never seen or heard an interview with Jack White that asks him how his guitar solo on “Ball and Biscuit” will cure cancer and stave off the zombie apocalypse. I once worried about the fairness of this paradigm, but I’m starting to see it as a show of respect. That people keep wondering how poetry will change the world seems to start with the implicit assumption that it could. I believe it already does, but not in the singular immediate way that seems to be demanded by some to justify the creation of literature. It is one of many human endeavors that, taken together, help to repair our minds into more thoughtful devices.

Art, be it poetry, music, sculpture, puppetry—the whole of it, inspires change on a personal level rather than a global one. This is important because the individual is the whole. The creation of art argues that people are connected, ideas are connected, the past and future are connected by this moment. Meanwhile, exploitation of the poor, drone strikes that kill hundreds of children, slavery, genocide, land theft—these are all acts that depend upon convincing large groups of usually well-meaning people that “they are not us.” Dean Young once said, "The highest accomplishment of the human consciousness is the imagination, and the highest accomplishment of the imagination is empathy." Poetry, along with every other art, is a tool for teaching and expanding empathy. Violence and injustice cannot endure empathy.

SB: I keep thinking of Tracy K Smith’s poem “The Museum of Obsolescence” from Life on Mars. In “How to Disappear Completely,” you acknowledge the idea of obsolescence and the fear of the human (or old machines) becoming obsolete. The poem urges the reader to “become origami. Fold yourself smaller than ever before. Become less.” Meanwhile, our culture continuously urges “more more more.” What’s going on here? Can we, as humans, resolve this conflict?

JM: Before delving into your question, I would like to comment on my fascination with the way association works in a collection of poems. Like you, I think of “How to Disappear Completely” as a poem about obsolescence, but I didn’t quite think of it as such until it was in a collection with “Mechanophobia: Fear of Machines.” It’s one of the more exciting aspects of putting together a collection of disparate poems and figuring out how they speak to each other.

It’s worth noting that the poem goes on to say “more in some ways but less in the way a famine is less,” which is to say quietude stands out in a cacophony. What’s more noticeable than a famine, meaning lack? I suppose the inverse truth of this is that “more more more” can equal less and less. The poem is trying to do a lot of things at once, but a center of gravity can be found in the simultaneous distress and solace that comes from solitude. Another is grief. I often render emotions by creating the space around it rather than going right at the thing. “How to Disappear Completely,” engages the weight and significance of loss by reifying an absence. The reader is promised she will finally be seen when she is missing from our world.

Can the “more more more” societal conflict be resolved? I’m not sure if this makes me a cynic or an optimist, but I’ve stopped looking at conflicts as things that either will or won’t be resolved, at least the kinds of conflicts good art tends to engage. The demand for more is just another way to say “desire.” Humans will never resolve desire and want. With the myriad ways we are exposed to greed and selfishness through all our media access, it’s easy to think of “more more more” as a modern phenomenon. But as a person of color writing in a country built on colonialism, genocide, and a vast slave workforce, I’m not allowed such delusions. So rather than wring my hands over how the conflict will be resolved, I investigate how we can live with such conflicts and work to become better humans inside of it.

SB: Technological advancement often makes obsolete people's knowledge and livelihoods. “On Metal” addresses a group of mechanics huddled “around a car, admitting some small defeat” because “Detroit’s building’em like robots now,” and they cannot fix it. For me, the theme obsolescence ties the book together. What were your intentions for this poem and this collection as a whole?

JM: Technological advancement is perhaps less frightening to me than to many of my peers. I’m not terrified of the presumed oncoming apocalypse facilitated by Facebook or the new Playstation. Television didn’t end the world and neither will Tumblr. I believe in something intrinsically human that will always exist outside of popular culture and the latest grown folk bugaboos. That intrinsically human thing is often ugly, narcissistic, and petty, but it was there before status updates and anonymous comments existed. Before our current age, “trolls” would just show up at your lunch counter, sit-in protest and dump ketchup and sugar on your head.

The other side of this paradigm is that some of the cooler things about people have also been around for a while and aren’t going anywhere. For example, our ache for the connection we find through art only seems to have been brought into relief by the modern era of immediate, low-effort gratification. If technology was as capable of short-circuiting what is at the core of humanity, there’s no way in hell I’d be able to walk into classroom after classroom of teens and preteens and get them excited to write poems. There wouldn’t be more poetry readings and journals and more Americans writing than ever before in the country’s history.

The focal point of “On Metal” is a kind of resignation about the decline of our machinery, but it is not nostalgic. If anything, the poem is reaching towards acceptance. The point isn’t that the men can’t fix the car because of time’s relentless march, it’s that we eventually have to choose between peace and stubborn arrogance when faced with mortality. The speaker hopes for that kind of grace (“a diminishment I’ll live with”) while also understanding the impulse to fight decay to the last cell: “...I get this...why my dad once fiddled daily with a dead Camaro, refusing to believe its silence.”

I’m not sure Hum hinges on the idea of knowledge and livelihoods becoming obsolete in the face of new technology, though abandonment and mortality are definitely key features. My intentions for the collection were to let the writing of individual poems guide the making of a book because ultimately, I’m trying to say something about dichotomy, the uneasy spaces between disparate emotions, and by extension, the uneasy spaces between human connection. For these reasons, if the collection hinged on a single idea, it’d be a failure of my broader project (which it very well may be, mind you, but art should risk failure). I’m crossing my fingers in hopes that I’ve written a many-hinged book with several possible openings.

SB: Hum weaves together the human with the robotic, and also formal poems with more open forms. What was your thought process in both crafting the formal poems (“Hum of the Machine God” and “Neat” particularly”) and including them in this collection?

JM: I think of all poems as having a formal project that must be defined by the needs of the particular poem. Sometimes a received form fits those needs perfectly, which was the case with “Neat.” I wrote it as free verse but realized quickly that the form was working against the emotion I wanted to evoke. I was looking for something that felt more cyclical and lingering, which the pantoum form is great for. The work of fighting the poem into the form gave it the torque I needed to get where I was going. This is typical of my process; when a poem doesn’t have a sufficient level of trouble, I look for something that threatens its safe little nest.

On other occasions, which are somewhat more rare, the received form gives me a launching pad for working out a concern. The mind tends to seek patterns and repeat them reflexively, so starting with a formal project can be useful in drawing out the untapped subconscious.

“Hum of the Machine God” started off as a challenge from my thesis advisor, Rick Barot, to help me see the core tropes and textures of Hum. He suggested I write a sestina using the six phobias that appear in the book as the six repeating words (machine, waiting, snow, etc). After submitting to the Beatrice Hawley Award, I put the manuscript away for 7 weeks. When I returned to it I wrote a second sestina from scratch, “The Hum of Zug Island,” using the same six words. The new poem illustrated what the first sestina was missing. I rewrote “Hum of the Machine God,” and now the two poems act as a pair of subtle bookends that tie the phobia thread together and, by extension, the core tropes of the collection.

Redundancy and tedium are always a danger with such an insistent form. Though it may seem sensible to use the most flexible words possible in a poem that demands they appear seven times, more inflexible words actually work better. This can be seen in Bishop’s “Sestina” with her use of “stove” and “almanac.” More recently Jonah Winter’s hilarious “Sestina: Bob” uses “Bob” as all six repeating words. What happens when the poet isn’t caught up on trying to use the words in various ways is the rest of the line demands more nuance and deftness. It relieves the pressure on repetition to carry all of the resonance and lets the repeated words do their more important job of cycling around in a more subtle, incantatory way.

SB: “I Do Have a Seam,” appears in two columns stitched together by the word “here” in the center. The poem can be read down either column, or across both—leaving the reader with three variations on the same theme, maybe more. Can you talk a little about the process of writing this piece?

JM: This poem falls into the same category as “Neat,” in that I originally wrote it as free verse and saw that it could be doing more formally. The form screamed at me one day in the editing process and the work that followed brought into relief what I saw as a paradox of healthy romantic engagement: the maintenance of individual self in midst of a certain, necessary vulnerability. As a student pointed out when I visited Indiana University (wish I had her name), the seam that splits the poem is also the space that holds it together. I couldn’t get at that kind of simultaneity in the free verse version.

The form is called “contrapuntal.” Its history, as I know it anyway, is that a poet who had also been a choral singer, Herbert Woodward Martin invented it. He wanted to capture an approximation of what happens in the contrapuntal musical form. Poet Tyehimba Jess in his collection Leadbelly, which contains several masterful contrapuntal poems, brought it into the contemporary American poetry spotlight recently. An exciting aftereffect is the popularity the form has enjoyed among younger writers and on the poetry slam scene for the past year or so.

Jamaal May is the author of Hum (Alice James Books, 2013) and The Big Book of Exit Strategies (Alice James Books, 2016). His first collection received a Lannan Foundation Grant, American Library Association’s Notable Book Award, and was named a finalist for the Tufts Discovery Award and an NAACP Image Award. Jamaal’s other honors include a Spirit of Detroit Award, the Wood Prize from Poetry, an Indiana Review Prize, and fellowships from The Stadler Center, The Kenyon Review, and the Civitella Ranieri Foundation in Italy.

Photo Credits. www.jamaalmay.com

One night, while on a train, Normal School Editorial Assistant Leslie Santikian asked Contributing Editor Adam Braver six detailed, slightly-rambling questions on the nature of fiction and truth, Marilyn Monroe, and myth-making compulsions. Graciously, he answered all.

By Leslie Santikian

Leslie Santikian: Your writing blurs the line between fiction and journalism, creating a hybrid that somehow touches both worlds; I think that's what makes me most enjoy reading your work. In light of the recent controversy surrounding John D'Agata and his philosophy that the search for truth doesn't necessarily mean accuracy and "fact," where do you think your work stands? Do you feel you have fewer boundaries to worry about because your work is technically "fiction"? Do you feel any obligation to "truth" or "fact" when crafting your books?

Adam Braver: In terms of this subject, my interest is not so much about a Truth that supersedes all else. Nor is it in the competition between fact and fiction. In fact, I’m most intrigued by how fact and fiction work together to create a so-called truth. Facts are facts. But it’s how they are arranged and linked and filled in that makes them become a truth or a history. And I just can’t help but believe that it is really the product of combining fact and imagination that get us to those truthful places. For the most part, I do feel obligation or allegiance to facts in my books. However, I also recognize the power of omission, as well as how a fact can have different implications when it is abutted or juxtaposed against other facts or imagined reactions, etc. That said, decisions do need to be made; and I strive to make them all from a position of strength, meaning if/when I might stray from the so-called factual, I know that I am doing it and have a definite reason (as opposed to it being from laziness or disregard). But the bottom line for much of this (in terms of my current thinking), is that I am much more drawn to collage—as opposed to linear storytelling. In part, it’s because I’m more interested in the ideas that attract me to the projects (as opposed to the storylines), and also because I’ve become more and more interested in space and spatial relationships in my writing. A more “collaged” style helps me get there. But as with a visual collage, the story and experience and theme it tells is all based on the relationships of the images to one another. And while all of those images are “real,” very often they’re only “real” in the most relative sense—meaning, that a cigarette advertisement from a magazine is just as fictitious as some made up story that might come from my head. But juxtapose that ad against a horrific wartime photograph, and suddenly they now are working in tandem to tell a real story that transcends their individual parts. Essentially, that’s what I’m trying to do with my writing these days. So, indeed, that the facts remain as facts is critical. But equally critical is recognizing that they only are facts, still waiting to be part of a story.

LS: Part of what makes your writing compelling is how far you take us into your character's lives: into their innermost thoughts, fears, wants, needs, memories. How do you get inside such iconic figures as Jackie Kennedy in November 22, 1963, and Marilyn Monroe in your newest work, Misfit, and show us who they are beyond their public personas? Do you have a process for doing this?

AB: One of those oft-quoted aphorisms about literature is that it can either show us the extraordinary in the ordinary, or show us the ordinary in the extraordinary. Obviously, with the two books we’re talking about here, the latter is the territory I’m wandering in. In as much as I have a process for this (and I use the word process loosely), it is about trying to access the ordinary in these people with whom we have anointed as extraordinary. So, for example, in writing about Jackie Kennedy on the plane ride back from Dallas, I am not trying to locate Jackie Kennedy and her persona, in as much as I am trying to identify with that base emotion that to me is universally human. By that I mean that one does not need to be Jackie Kennedy to understand grief and loss, or the fear at losing one’s sense of place in the world. Frankly, I’m finding those places inside of me, more than trying to identify them in these mythical figures. As I alluded to earlier, part of this stems from the fact that I’m less interested in the stories of these people as public figures, as opposed to making some kind of art out of their experiences to understand more universal themes on culture and humanity.

LS: Your new book, Misfit, feels especially timely, considering the recent, reinvigorated interest in Marilyn Monroe's life in popular culture—the movie My Week With Marilyn, the TV show Smash, etc. What drew you to Monroe for this book?

AB: Well, the timeliness is somewhat accidental. I had been challenged to write a short story about her—a challenge I accepted. I didn’t know much about her; she wasn’t someone who was ever on my radar, other than the basic biography. But as I began to research a bit about her for the story, she became intriguing to me as a character to work with. In part, I was drawn to her constant reinventing of herself, which seemed to me to be emblematic of how we view the dream of our culture. And perhaps most fascinating to me was the idea that one can reinvent one’s self to the point where the reinvented persona begins to overwhelm or overtake the person; in Monroe’s case, it was the idea that the persona of Marilyn Monroe became larger than the person who inhabited it. I saw this both a phenomenon of the larger culture, but also one that symbolized the struggle for individual identity.

LS: A prominent theme in Misfit is the tension between Monroe's public persona and private self—and, even beyond that, the love/hate relationship she had with that private self. What made you want to explore those tensions? Do you consider these tensions particularly powerful when you're writing iconic characters?

AB: I think that is a tension that I am generally interested in exploring—the negotiation between the private and the public self. In her case (as with most iconic figures) it seems to be greatly exaggerated, as that chasm often is what is so intriguing about them. Also, as with any character, I find those who are most enigmatic to be most interesting (I’m saying that, of course, as a writer). That unknown private world is the place I want to get to—often the place that I imagine has been buried or denied or forgotten; those moments where the people are stripped bare and ordinary and often at their loneliest because they have come to believe they are not allowed to be that person anymore. Or so I imagine it.

LS: You also seem drawn to how people become mythologized, shaped into a larger-than-life version of themselves. I'm thinking of Monroe, but also John F. Kennedy, Sarah Bernhardt, etc.—all subjects of your work. Are you speaking to our larger need for god-like figures in our society? To other compulsions?

AB: I think it’s more about being intrigued by the idea of mythology—both the notion of self-created mythologies, and culturally ordained mythologies (and perhaps the intersection of the two). You know, it’s a funny relationship between having these god-like mythical people (or at least reifications), because on the one hand they can validate some sense of who we are culturally, but individually it can also make us feel really small and wanting and not enough.

LS: Do you have any idea or person in mind for your next book? Anyone you've been waiting to write about?

AB: I’ve been researching (and doing some writing) about a woman named Kay Summersby, who was Eisenhower’s driver during WWII. There were rumors of an affair between the two of them—although that’s really the least of my interest. At this point, I’m much more intrigued by how this seemingly unlikely Irish woman would find herself regularly with a front row seat at major, worldwide historical shifts.

Adam Braver is the author of Mr. Lincoln’s Wars, Divine Sarah, Crows Over the Wheatfield, November 22, 1963, Misfit, and The Disappeared. His books have been selected for the Barnes and Noble Discover New Writers program, Border’s Original Voices series, the IndieNext list, and twice for the Book Sense list; as well as having been translated into Italian, Japanese, Turkish, and French. His work has appeared in journals such as Daedalus, Ontario Review, Cimarron Review, Water-Stone Review, Harvard Review, Tin House, West Branch, The Normal School, and Post Road.

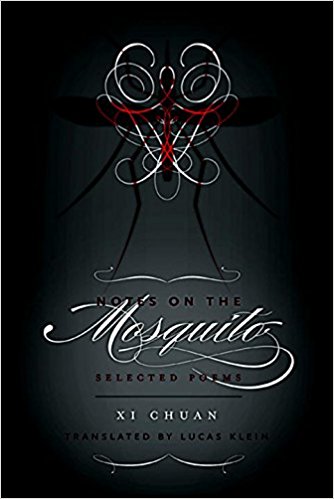

Editorial Intern Michael Gray asks Chinese poet Xi Chuan and his translator Lucas Klein tough questions concerning process, navigating translation, and the relationship between literature and reality. Xi Chuan is one of contemporary China’s most celebrated poets, having won the Lu Xun Prize for Literature (2001) and the Zhuang Zhongwen Prize (2003). Lucas Klein performed the English translation of Xi Chuan’s book Notes on the Mosquito: Selected Poems (2012).

By Michael Gray

For Xi Chuan: What elements of your original text do you find are most altered in the process of translation?

XC: 我自己写的东西,尤其到后来,有时会非常“直截了当”,而“直截了当”的东西其实不好翻。我自己也做翻译。据我的经验,意象相对来说容易翻;音乐性,特别是旋律,虽然译文与原文不好完全吻合,但还是能够找到相应的解决办法。但直截了当地表达思想观念的东西翻译起来很容易丧失诗意。直截了当,是晚年Borges看中的品质,因为他早年玩过巴洛克。表达观念是Milosz所赞成的,因为他来自东欧。这两人都把脚迈到了抒情诗的门槛之外。我曾对一位加拿大诗人讲过,我的诗,容易的地方我会尽量容易,但难的地方我也会尽量难。难,我指的是我会在中文中通过词语、语式传递尽量大的信息量。我的诗向着现实和历史敞开。现实和历史的跌宕起伏以及浑浊,会被我变成语言方式。我喜欢将当下口语和古老表达、松弛和紧张、日常和古怪、透明和浑浊、绝然和暧昧混合在一起。翻译者不得不经常进行脑筋换挡。还有,中文和英文毕竟是两种语言,两种语言牵带出的文化记忆,所面对的诗歌上下文并不完全一样,所以个别在中文里有意义的表达也许在英文里没有意义。但Lucas已经尽了力。他的工作很出色。

Lucas Klein’s translation: In my own writing, especially recently, I’m often very blunt, but bluntness can be very hard to translate. I’ve done a lot of translations myself, and in my experience imagery is relatively easy to translate; with musicality, or particularly rhythm, though it’s hard to match the translation perfectly with the original, it’s still possible to find comparable solutions. But with ideas expressed bluntly it’s easy to lose the poetry. Bluntness is a quality of late Borges, because in his early years he was playing with the Baroque. It’s also a notion of expression Milosz was fond of, coming from Eastern Europe. These two stepped outside the bounds of lyrical poetry.

Talking to a Canadian poet one time, I said that with my poetry, when it’s easy I try to have it be as easy as possible, but where it’s difficult I try as hard as I can to make it difficult. By difficulty I mean that I try to transmit as much information through vocabulary and expression in my Chinese as possible. My poetry opens up to reality and history; the uninhibited undulations and turbidity of reality and history will turn into modes of language. I like to mix up contemporary slang and antique elocution, the slack and the tense, the quotidian and the bizarre, the opaque and the clear, the direct and the ambiguous… the translator has to find ways to stay alert. English and Chinese are two very different languages, each bringing along its own cultural memories, facing two different poetic contexts, so any expression that might be significant in Chinese may end up being insignificant in English. But Lucas did a great job. His work is outstanding.

For LK: A line in the poem "Three Chapters on Dusk," reads "a ray of light, we become history" from Chinese: "作为一种光线,我们就是历史." I literally translate "就是" to mean "is" or "are," specifically emphasizing a certain state or existence, but in the context of the poem, "become" makes more sense. Why did you choose that word?

LK: I wrote in the introduction of Notes on the Mosquito, “I am motivated by a belief that the reader not only wants to know but can know both what Xi Chuan says and how he says it, both his images and his style, both his allusions and his elusiveness.” At the same time, too narrow a conception of how limits the work. There’s a long history of philosophizing about "being and becoming," but I’m not sure that such discussion is relevant to a judgment about whether, in this translation of this poem, I should have said “as a ray of light, we are history,” instead of “a ray of light, we become history.”

It’s easy to go too far along these lines, but sometimes, to be faithful to the source text you have to be unfaithful to the word. Words often have more than one meaning, so we have to pick the right one. For instance, I noticed in one of Xi Chuan’s recent translations of Gary Snyder that he took the word "shop" and translated it into shangdian 商店. Well, that’s a shop, certainly, but I think Snyder is referring to the shop you might have in your garage, where you’d keep your hatchet, if you had one. But not many Chinese people have a "shop" like that in their homes, so even if it’s a mistranslation, it’s a mistranslation that helps Chinese readers access the poem. I noticed a similar moment like that in one of my translations of Xi Chuan: I translated a line of "Rereding Borges’s Poetry" as "annotat[ing] the aporia of history." More accurately, it would be "the lacunae of history." "Aporia" and "lacuna" are not quite the same (though they’re related), but ultimately I not only felt that "aporia" alliterated better with "annotated," but also that it worked into how Borges has been read by critics in the west, who tend to see his writings more defined by the aporia—or paradox or puzzle—than by what they leave out, or their lacunae. Technically, it’s a mistranslation. But I think it resonates with readers in English this way. Of course, at other times the opposite is true, and you want to insist on difference, to keep all notions of the poetic or literary from being subsumed into a common cultural ignorance.

For XC: You comment on a writer's engagement with a broader landscape, that "one's sense of reality is shaped by one's tradition." How does this statement relate to the poem "Notes on the Mosquito"?

XC: 我文章中讨论的是文学、诗歌与历史、文化、现实的一般关系的问题,表达的是我的基本态度。文中我主要是在寻找创造力的来源和创造性工作的坐标。而《蚊子志》是一首具体的诗(同时也是偶然成为了这本书的书名)。在具体写作时我不曾想到那么多理论性的问题。当我面对“蚊子”,我面对的是一套世界背后的逻辑。那套逻辑有它的荒诞性,而发现这种荒诞性让我愉快。当然回过头来想,这种荒诞性是与我的生活密切相关的。蚊子,就我的记忆,在古代,几乎不曾被诗歌书写过。它们等我到今天,进入我的诗歌。我热爱中国古代文化,但我反对“寻章摘句”式地运用古代的文化资源。我不需要着意向任何人显示我的中国文化身份,我只需对周边事物和我的经验保持一份诚实即可。中国古代文化以及历史和政治,已然自我转化为我身边的事物。我无法像个不在此地的人在一定距离之外表达赞成或批判。在这首诗中,蚊子当然不仅仅是蚊子。它像一个小寓言中的主角,但又是一个蕴意不明的主角。

LK’s Translation: My essay is about problems concerning the relationship between literature and poetry on the one hand and history, culture, and reality on the other, making plain some of my basic attitudes. It’s me looking to coordinate the sources of creativity against the work of creation. “Notes on the Mosquito,” meanwhile, is an individual poem (which happened to become the title for the whole book). In writing any particular poem I don’t tend to think about theoretical problems. Looking at the “mosquito,” I’m looking at a whole logic in back of the world. That logic contains its own absurdity, and discovering this absurdity makes me happy. When I look back, I find that this absurdity is intertwined with my own life. Mosquitoes, as far as I can recall, were never written about in poetry in ancient times. They’ve been waiting for me so they could appear in my poems! I love ancient Chinese culture, but I can’t stand the hackneyed way ancient culture gets used as an embellishment to discourse. I don’t need to demonstrate my Chinese cultural identity to anyone; I just need for there to be sincerity between my experience and the things around me. Ancient Chinese culture, history, and politics have transformed into those things around me. I have no way of expressing judgments of praise or blame from afar. In this poem, the mosquito isn’t just a mosquito; it’s a protagonist in an allegory, but the meaning of its role is unclear.

For LK: What English do you have in mind when you translate from Mandarin? How does this choice affect the translation of poems and audiences' possible interpretations?

LK: This is the kind of question I wish people considered more often when thinking about translation. This really defines the difference between translations, the version of the target language the translator has in mind for her or his translations.

The English I have in mind is the American English used in poetry of a certain kind for the past century or so. This is an English recognizable as in the tradition of avant-garde poetry, but it’s got a wide range—the kind of range that allowed, for instance, Ezra Pound to write “The gew-gaws of false amber and false turquoise attract them. / ‘Like to like nature.’ These agglutinous yellows!” one year and “But you, Sir, had better take wine ere your departure” the next. This is how, I think, I was able to translate in a way that Jennifer Kronovet described, in her piece on why Notes on the Mosquito should win the Best Translated Book Award in poetry, as not having “made these poems American, but rather allowed us to hear Xi Chuan’s poetics and ideas in an American idiom, in an English that is alive with personality.” (We’ve been very fortunate in the published reviews our book has received—they’ve been very enthusiastic about both the poetry and the translation—but this was one of my favorite moments).

I mention Pound on purpose, not only because one of these lines is from his invention “of Chinese poetry for our time,” as T. S. Eliot put it, but also because he’s the father figure of American avant-garde poetry (what a complicated man to have as your father!) and the father figure of the press New Directions—which of course is our publisher for Notes on the Mosquito. Some other press might have published Xi Chuan into a different English (on my xichuanpoetry. I have links to other translators’ work), but I want to emphasize that I have in mind an English that descends from the Pound line not only because of my tastes or the heritage of our publisher, but also because I find Xi Chuan’s Chinese to occupy a similar space in the layout of contemporary Chinese literature. Pound and the poetic movement he was part of were important in the formation of modern Chinese poetry, too, and more specifically for Xi Chuan, as well.

For XC: What is your reaction to seeing your work in another language?

XC: 我很高兴看到我的诗歌被翻译成外语。翻译使我的诗歌有了更大的飞翔范围。借助Lucas的翻译,这些诗得以找到另外一些工作着的大脑。如果它找到了,那么,这就是对于作者的最大的回报。另外,通过阅读译文,我也得以获得了观察自己的陌生的眼光。《蚊子志》不完全是我的书,而是Lucas与我,我们的书。

LK’s translation: I’m very happy to see my work translated. Translation gives my poetry a much wider flight radius, and with the help of Lucas’s translations, these poems were able to find a greater number of active brains. And if they found them, well, that’s the greatest reward a writer can have. On top of that, reading these translations has given me new eyes with which to observe myself. Notes on the Mosquito is not just my book, but is our book, mine and Lucas’s together.

For LK: How do you start your translation process? What responsibilities and difficulties do you encounter when trying to maintain the authenticity of the original language's meaning?

LK: I start the translation process by reading the poem in Chinese, mentally converting certain words and phrases into English as I go. Then I put it into English line by line, after which I go over it and correct any mistakes I can find. Then I read it again in just English and try to smooth it out, make sure it sounds right in English with the Chinese still fresh in my mind. Then I put it aside for as long as possible, and after forgetting it go back and read it in English to make sure it sounds right with the Chinese not in my mind at all. Then I’ll go back and check it against the Chinese to see if I’ve made any mistakes. Then I’ll share it with as many different kinds of readers as I can—readers of Chinese, readers of poetry in English, readers of translation (whether they know Chinese or not)—and take in their comments. At some point, I decide that there’s nothing else I can do, and that the poem in English is the right translation for the poem in Chinese. As I said, I believe translating to be not only about the what of a poem but the how, as well.

One thing that comes to mind is Xi Chuan’s phrase 穷尽一个人, in “Exercises in Thought,” where he talks about Nietzsche’s philosophical aims. It’s straightforward enough in Chinese, but the most available translation into English would be “the exhaustion of a person”—but “exhaustion” more colloquially has to do with being tired out. I had to come up with something else, and eventually settled on “The depletion of a person, that was Nietzsche’s work.”

I adamantly do not see translation as defined by “difficulties” or “problems.” Sometimes it’s hard, but the words I use to describe translation—and particularly this translation—have more to do with joy, excitement, discovery, interest, and necessity.