By Sean Patrick Kinneen

Sean Patrick Kinneen: How did you start writing, and who have been your poetry mentors?

Christine Poreba: I started writing poems in high school, most specifically for a senior project of our choosing for which I wrote and designed a booklet of poems called Refuge. [Sigh of slight embarrassment here.] My mom was an English teacher at the all-girls school I went to and she, a poet herself, agreed to be the adviser for the Poetry Club my best friend and I started. It was through my mom that I became aware of a high school poetry workshop happening at Academy of American Poets.

In college, I mostly wrote on my own but the summer before my senior year I took my first poetry class at what is now New York Writers’ Workshop but was then called The Writer’s Voice. My first class was with Donna Masini, whose handouts from that class 20 years ago — with ideas like writing down snippets of dreams and using freewrites — I still have and go back to. I remember her saying one day, “some days, only poetry…” in reference to how poetry can get us out of our funk, and the thought of that rang true for me. I also took a class with Elaine Equi, who gave me my first look at less narrative poetry, which helped widen my horizons. After that I took many wonderful classes with teacher Mary Stewart Hammond, who became my mentor. She both gave me confidence in my natural abilities as well as gave me tools and a strong inner voice to call upon in writing and revising poems.

SPK: What was the first poem you read? When was the last time you read it?

CP: One of the first poems I really remember reading, and also having recited to me by my mom, was "Spring” by Edna St. Vincent Millay. I never liked the season and my mom, who gave me an old copy of Renascence, one of my first owned poetry books, used to recite the opening lines to me:

To what purpose, April, do you return again?

Beauty is not enough.

You can no longer quiet me with the redness

Of little leaves opening stickily.

I know what I know.

I think the last time I read it was shortly before my son was born — in the spring — at which point my feelings about the season changed a bit.

SPK: Where did you grow up? Can you talk about how that place came to influence some of these poems?

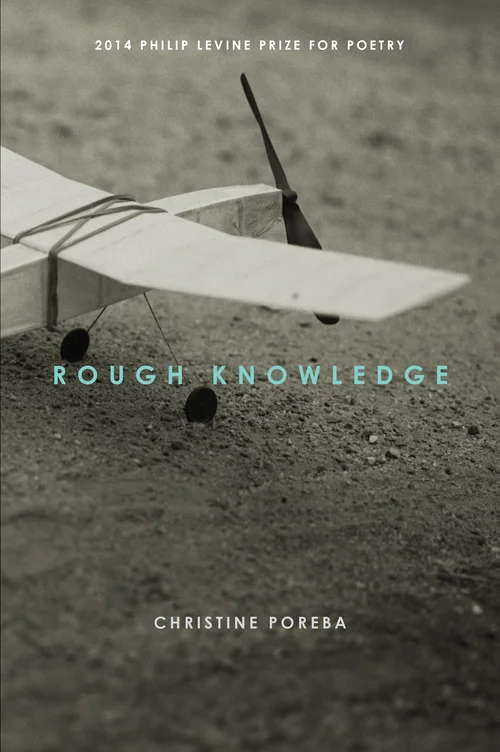

CP: I grew up in New York City. I moved to Florida to get my MFA at the University of Florida in Gainesville and it felt like it took me a while to adjust to writing here. The energy and streets of New York were so much a part of my writing before I moved. It took me a while to get used to the quiet. I touch on this in my poem “Alight.” The city itself took on a more nostalgic tone in my work once it became the place I used to live. Ironically, the longer I live away from it, the more it takes on a separate entity in my poems. When I lived there, the very energy and happenings I observed became what I was writing about, but in Rough Knowledge it becomes part of my memories and takes on more distance. The last two poems of the first section of the book revolve around September 11th as I experienced it as a New Yorker. Since it’s where I’m from and this is a book about moving from where you’re from to where you are, it is an important part of these poems.

SPK: How long did you work on your Rough Knowledge manuscript before sending it out to contests?

CP: It was a long and slow process. I experimented with various compilations — one of which was a chapbook manuscript that included some of the poems from Rough Knowledge and was called Wide Stretch of Sky — after getting my MFA, but the skeletal version of Rough Knowledge did not begin to appear until about four years after that. I then entered it into contests for several years, and every year it changed slightly.

In 2014, I read an article by April Ossmann in Poets and Writers, Thinking Like an Editor: How to Order Your Poetry Manuscript, and that was very influential and led me to make significant changes before sending it out that fall, for, as it turned out, the last time! So, to answer your question, I worked on it for a few years before I first sent it out and revised it slightly for the first few years of sending it out and then more majorly the last year. I am definitely not a fast worker when it comes to manuscripts!

SPK: In your book, I saw subjects of family and memory, but even more subtle, I think, of death and rebirth, dark and light. Did those ideas inform the way you ultimately decided to organize this manuscript? Do you see all those subjects as being connected, cohesive in some way?

CP: This question feels connected to the last one for me. One of the things April Ossmann talks about is color coding poems by theme and using that as a guide for how to order the poems. In earlier renditions of the manuscript, I had often ended up grouping the poems chronologically in the order that events recounted had occurred. But because the poems themselves are narrative, I realized this sort of order didn’t really work so I decided to go with what Ossmann calls a lyric ordering, “in which each poem is linked to the previous one, repeating a word, image, subject, or theme.”

So yes, I do see all those subjects as being connected. Rough Knowledge is about a series of journeys for the speaker, from childhood to adulthood, from being single to being married, from an old home and old life to a new home and new life, from fear to calm again, from a simple every day thing to a huge tragic thing seen or read about. Also journeys of a house with its history of past inhabitants to taking on a new shape of its current ones and of a garden, going from empty to being filled with tiny seeds which may or may not grow. I chose “Toward Home” as the first poem because I felt like it introduced a bunch of these themes. After that, I wanted the book to have somewhat of an accordion feel, going back and forth between appreciation and wonder of a moment to fear and sorrow at darkness and loss since that is more what life itself is like rather than organized sections of different periods of time.

SPK: How did the title come about? Did the idea of transition from one life to another decide, perhaps unconsciously, the book being in two parts?

CP: I played around with a bunch of different titles, one of which was Containable. Rough Knowledge was actually the earlier title of the poem “The Turn,” which I see as being at the heart of the book. It centers around the idea that the knowledge we have when embarking on any journey is always incomplete, as in a rough draft, and can also be rough as in difficult. I liked how it seemed to encompass all the themes of the book. In an earlier version, the book was divided into three sections, but I ultimately decided on two because it felt right, I think in part because that felt connected to the binaries I see as being essential to the book: joy/tragedy, light/dark, old life/new life, sky/ground, internal/external, containment/space. Like two halves of one thing.

SPK: You use stanzas of two and three lines quite a lot. How are they particularly important or meaningful to you?

CP: That’s a great question. I think I did that more in these poems than I do in my more recent work on different themes. Many of them would start out not that way but when revising, that form often ended up feeling most fitting for the content. Philip Levine Prize judge Peter Everwine said my poems felt like breathing, inward containment, outward space, and I loved that. I think that does have to do with it — also, a lot of these poems center around the first years of a marriage, so I think groups of two lines felt like they worked, and the three lines feel like they represent the two of us and a third as the old self one is leaving at any moment, or the two people and the moment.

This is all post-analysis. At the time I guess it just felt right. I recently read an interview with Edward Hirsch about his book Gabriel and his use of tercets. He said one thing that drew him to it is that each stanza has a beginning, middle, and an end. I think that’s part of why it felt like it worked with the idea of leaving an old life and beginning a new one and with my narrative style.

SPK: What draws you to those French forms, the pantoums and the sestinas?

CP: In the very first workshop I took in 1996, the summer before my senior year of college, the teacher Donna Masini and my classmates started calling me Christine Sestina. She assigned one and it was the first time I’d written one. I remember I wrote it on a bus traveling back to NYC from Philadelphia the night before it was due and that surprised people. It was called “Keeping Still with Water” and was basically the story of the visit I had just come from. I liked how the repeated words helped me explore something different in each stanza but also kept things centered around that same moment. I’ve probably only written a total of five or so. Some of them don’t work. I think I was first assigned a pantoum when I was in grad school. The repetition of whole lines feels like it’s fitting for a darker subject, that feeling of being trapped a little bit. I haven’t been writing in those forms lately but I am glad to know they are there to try out when I might need them again.

SPK: Are there any poems you decided to leave out?

CP: Once I became clearer about the themes of the book, I was able to narrow things down a bit and take out poems that didn’t seem to fit in as well or were not as strong. Every year that I made slight revisions I took out a few poems and put in a few newer ones, so it was pretty much in flux. I think I took out about five poems in my final version.

SPK: What have you been reading lately?

CP: Most recently I've been reading Mark Wunderlich, Philip Gross, Imtiaz Dharker, Erin Belieu, and Beth Ann Fennelly. I find myself returning to re-read Dana Roeser, Sidney Wade and Edward Hirsch for momentum and renewal. I've been especially interested in other people's first books lately, and two I totally loved is Alison Prine's book Steel, which just came out, and fellow Anhinga Press poet Robin Beth Schaer's Shipbreaking. Also, The New World by Suzanne Gardinier.

SPK: What’s the next writing project for you?

CP: Well, New York City appears in my next manuscript in an even more historical lens, through the retelling of the experiences of my grandparents, Polish immigrants in the 1930s to the Lower East Side, where I grew up and my parents still live. While Rough Knowledge centers around the journeys of one speaker, my second manuscript examines multiple journeys. Poems involving my grandparents and drawing on New York City history, from visits to Ellis Island, the Tenement Museum, and my own childhood neighborhood as well as historical readings, make up one thread. The other two threads are those of the experiences of my adult English as a Second Language students in a new land and language and those of a child and mother learning their own new world. I am in the process of finishing up this manuscript. Some of my newest poems are informed by my son’s questions about everyday occurrences and wonders like machinery and space and balloons in the sky.